I cast my vote for the National League for Democracy (NLD) in the 2020 general elections, and when, in the wake of the coup, the National Unity Government (NUG) emerged, I stood behind it without hesitation. To be sure, there were flaws from the beginning. But I was confident that they would address them. When lives are under constant threat with insecurity for four years, is it not reasonable for a citizen to expect a better performance from a government he supports?

When calls for reform grew louder—especially from prominent voices like Dr. Tayzar San—I was therefore on tenterhooks to see how the NUG would respond. As someone who follows politics closely, I began collecting critiques, not to undermine, but to understand. I was trying to figure out what matters most now.

Response to criticism

Criticism has accompanied the NUG since its inception. But when someone as prominent as Dr. Tayzar San voices concern, it resonates more widely. And when people are desperate for direction, the urgency is amplified.

Yet nearly a month after his public critique, the NUG’s response has been tepid at best. The only official comment came from NUG spokesman U Nay Phone Latt in a regular press briefing where he vaguely promised to improve performance and representation. No details; still unclear to date. Meanwhile, Acting President Duwa Lashi La made a symbolic visit to liberated areas.

This is not the first time the NUG has promised change. Earlier this year, its Foreign Minister Daw Zin Mar Aung said at an interview: “It is time for us to ask this question: will we be the ones to lead change in 2025, or will we be changed by it?” More than six months later, I am still waiting for her answer.

Is the NUG listening?

The NUG’s responses lean toward discarding criticism as propaganda by the military regime or even accusing people in the resistance of playing to the junta’s tune. To be sure, the regime is actively sowing division through propaganda. But a democratic government must do better than to dismiss dissent. Dismissing uncomfortable voices as somehow being “not the real people” is the mindset of authoritarianism.

Even prominent writer Ma Thida (Sanchaung) apparently shares this view. In a recent article, she argued that not all the social media criticism of NUG leadership can be considered the expression of general sentiment. “We need to ask: how representative is this critique of ground-level sentiment? We need to consider that many of those who criticize on social media are disconnected from the realities on the frontlines.”

She cited a survey by the research group Blue Shirt Initiative to support her view—but apparently overlooked the fact that the survey asked only about trust levels, but not about why people trust, whether their trust has increased or decreased, whether there are areas they want to see improve, and what shortcomings they see.

Trust, when granted, carries responsibility. In the survey, respondents say they trust the NUG most—in the absence of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. That trust must be honored not just with words, but with concrete actions.

The truth is that those calling for reform, including Dr. Tayzar San, are not speaking in a vacuum. Their critiques reflect a broader frustration.

Rethinking the metrics of progress

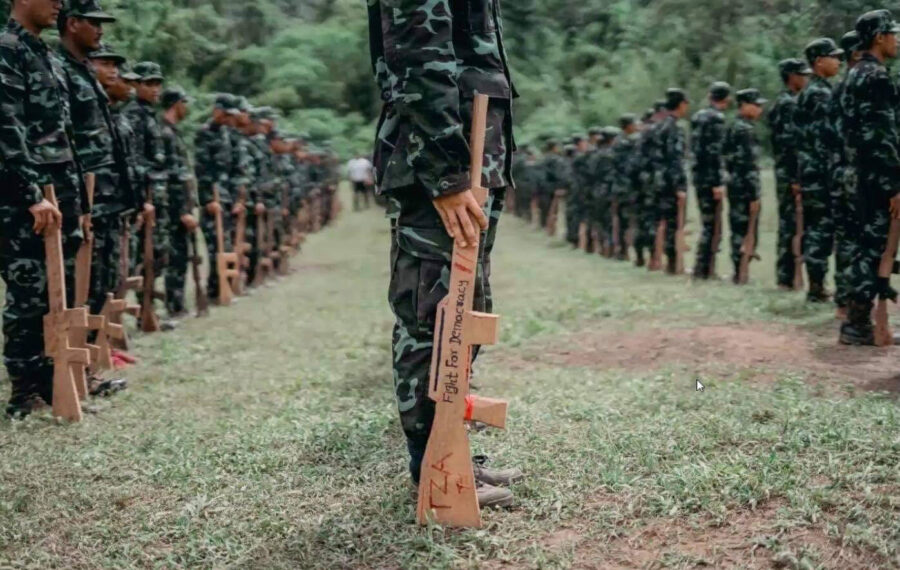

Some point to territorial gains by resistance fighters as proof of the NUG’s success: “We started this revolution with our bare hands—now look how many towns we’ve taken.” But when those towns are retaken by the military, the narrative shifts again. “That’s natural in war,” they say.

From a government that claims to represent the people, we need better metrics. I would propose this: measure progress by how much the suffering of the people has been reduced, and how well civilians have been protected. That is the true test of a people’s revolution.

The NUG promised changes in early 2025, but while it has been dragging its feet over the past six months, the regime carried out at least 1,307 airstrikes that resulted in 1,064 deaths and nearly 100,000 new internally displaced people. The total displaced population now exceeds 3.5 million. The military is the perpetrator—but failure to prevent harm carries its own burden.

I do not expect miracles once the NUG changes. I accept that other revolutionary groups, small or large, are also responsible for the overall strategy of this revolution. But should not the NUG, as the government that wants to win public trust, take the lead? The time is not unlimited.

More competent than the military?

Experts, analysts, and political activists have already offered a range of perspectives on what the NUG should reform—and how. As I follow these discussions, I find myself drawn to one particular question.

If we focus purely on capability between the military and the NUG, who demonstrates greater competence? Ideally, I would like to see an analysis that compares the performance of individual ministers—much like how boxers are evaluated—based on concrete data and indicators.

Of course, “competence” does not mean “who has better intentions.” Rather, it refers to who is able to fulfill the goals and responsibilities expected of them in their respective roles.

NUG needs a sense of urgency

The regime has rebranded its rule, started preparing for elections, and increased diplomatic engagement with foreign governments by using the proposed election as an excuse. And these moves are working.

By lifting the state of emergency and staging gestures of civilian transition, the regime is executing a calculated strategy to legitimize its grip on power. Everyone knows the generals will not surrender control—but they want the world to believe they might.

Of course no revolutionary group should make peace with the regime by citing the suffering of the people as an excuse. People have been suffering immensely, but making peace with the regime will only aid its election plans, thereby prolonging the suffering.

By contrast, the revolutionary camp remains fragmented. The strategy vacuum is evident. The NUG’s delay in reform is a strategic vulnerability for the people. If the NUG continues to move so slowly, we must ask: will it ever truly change? Or will it remain stuck in rhetoric? Does it have the will to transform—or just the words?

The longer leaders and institutions stall, the more the people suffer. And as a citizen, I find myself asking the same question of every group involved in the revolution: are you truly ready to change? So far people are clinging to this hope.

Leadership must be grounded in reality

To conclude, I want to reference a social media post by journalist U Khin Maung Soe. He titled it “Come Home,” pairing it with a photo of the NUG president on the ground inside Myanmar. The post reads: “The remaining ministers, deputy ministers, and secretaries (except for those who truly need to stay abroad) should start returning home. If you can’t return, then take on a different role. Do you still want to lead without living among the people? If you’re capable of shame, you should be able to resign.”

The phrase “If you’re capable of shame, you should be able to resign” made me reflect—does this imply that U Khin Maung Soe still has expectations for the NUG? If it were up to me, I would first ask whether the NUG is truly capable of shame.

(This passage seems to broadly target the entire NUG. That said, I feel deep respect for the brave individuals—whether under the NUG or in various other entities—who have risked their lives and continue to serve with dedication. My criticism is directed at those in leadership roles. There are both capable and incapable individuals within the parallel government. But as long as they remain part of the same governing body, they share its responsibility—for good or ill.)

Desmond is an international development researcher specializing in peace processes and transitional reform