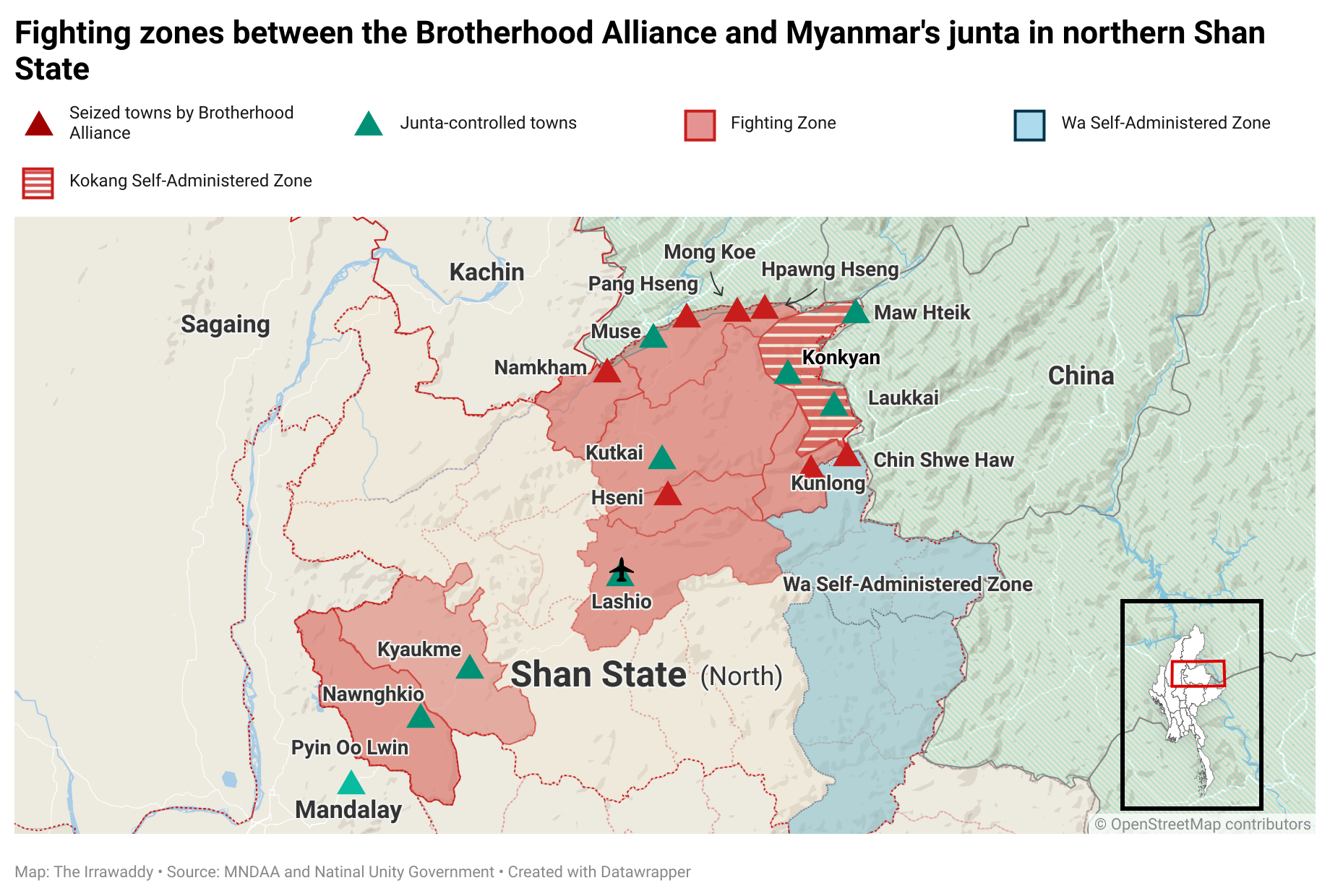

In the past 10 days the military situation in Myanmar has changed vastly as the Northern Alliance Brotherhood of ethnic armed organizations – the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), Arakan Army (AA) and Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) – has secured large swathes of territory across northern Shan and effectively blocked the junta’s access to the border with China.

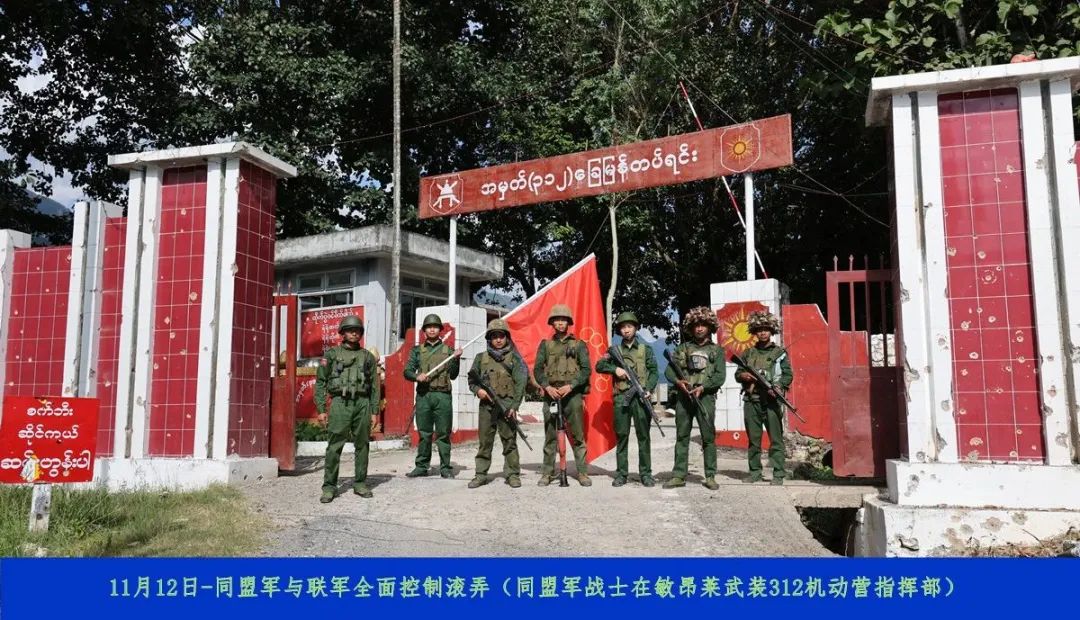

Under the guise of Operation 1027, over 150 military outposts have been captured while the list of towns taken by the resistance is increasing by the day.

It is important to contextualize Operation 1027 within the wider history of what has unfolded in Myanmar since the military’s coup in February 2021.

The ongoing successes of Operation 1027 were made possible by 32 months of revolution, both armed and peaceful. In turn, Operation 1027 makes possible the wider waves of junta collapse that can now be expected. Operation 1027 is a historic milestone that built upon what had preceded it and will catalyze everything that comes next.

It is painful to belabor the point, but Myanmar’s conflict is a revolution. The selection of this word is not sensational. Myanmar’s war is defined by a people in mass rebellion against military dictatorship.

Yes, there is a wider history of civil wars across the country and there are massive political cleavages still existing, but the war since 2021 is not a simple continuation or escalation of what came before. It is a revolution in every empirical meaning of that word. Namely, resistance to the junta is driven by a society’s desire for a fundamental rupture with its past – a new beginning freed of military dictatorship and defined by inclusion. Foreign cynics can scoff at this point, but masses of Myanmar people do not.

This specific phenomenon – revolution – is the basis for understanding what has happened and what might happen next. Wars driven by popular uprisings against a near universally loathed but deeply entrenched dictatorship are defined by inertia and trajectory. Dictatorial regimes – for instance, recently in Sudan and Iran – most often succeed in snuffing out resistance to their rule fairly quickly before it can coalesce as a wider social movement determined to enact deep change, even if that means through arms.

In contrast, Myanmar long ago passed a threshold (I would say by the end of the 2022 dry season) where the junta could no longer realistically crush resistance to its rule. Instead, resistance to the junta continuously expanded across the country to an extent that the prospect of success became increasingly clear to those on the ground.

The simple fact that Operation 1027 happened attests to this point.

The Northern Alliance Brotherhood (NAB) had long proclaimed moral backing for the Spring Revolution and provided some material support but expressed no desire for large-scale participation in it. That these three EAOs have gone all in against the junta and done so in partnership with a wide range of newer resistance actors, both inside and outside of Shan, is surely based on their own belief that it is not a pointless exercise coming at great cost.

Moreover, notions that all EAOs simply want their own local control or are merely proxies of China are grossly unfair to those fighting the junta now. One wonders how many times EAOs – from the Karen National Union (KNU) to the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and now those of the NAB – must state that they are part of a wider, larger national effort that fundamentally seeks a different future for the whole country before foreign cynics stop dismissing their statements as charades. Why shouldn’t we believe them?

The other visceral logic driving Operation 1027 was surely a straightforward assessment of the military balance. This was not confined to the last few months; it was a view of the wider trajectory of the war from the past two-and-a-half years. This trajectory has increasingly favored the resistance since at least the end of the dry season of 2022 but became steeper over 2023. Operation 1027 was implemented by three of the most competent, strategically inclined EAOs in the country. It was not a rash, opportunistic decision and I don’t believe one instigated by China. Operation 1027 was a bullish statement of confidence, not a coerced half-step by unenthusiastic actors.

The stark truth for the military is simple and becoming bleaker day by day: it faces too much resistance in too many places and doesn’t have the depth to recover. This has been the war’s trajectory for at least 18 months now. The military doesn’t have intact reserves at the unit level that it can move as needed. Its inability to launch any notable counteroffensives since Oct 27 attests to this reality. What it has is already spread across the country. If there was ever a time to use such reserves, the past two weeks was it. The failure to do so will just escalate the collapse because it demonstrates the hollowness of the military. It also speaks to a simple threshold already crossed: if the junta moves troops from one area to another it is now a zero-sum game. Stay or leave, but either way it will lose something. Operation 1027 greatly benefited from the movement of junta forces earlier in the year from northern Shan to fight in Karenni State. This brutal reality check for the junta’s military planners is only escalating.

There is another stark reality that confronts the junta, one that it never prepared for. Anyone who visits the “battle victories” display at the Tatmadaw museum in Naypyitaw will be struck by how much emphasis the military places on its history of seizing hilltops. This makes sense when fighting counterinsurgencies in mountainous areas. But Myanmar’s junta is no longer focused on strategic hilltops. It is sprawled across the country, fighting in valleys and the central plains to defend urban garrisons and the key highways linking them. Being in small battle-worn units, spread too thin, and with no strategic depth left – namely to maneuver larger, relatively intact units as needed for sustained counteroffensives – means that the military is massively overextended, irrecoverably so. It is a simple problem of geography and manpower.

This is made even more pressing by a simple observation: Myanmar’s revolution is defined as a national collaboration between majority and minority communities. The military never imagined it would face a widescale revolt by Bamar regions in full collaboration with major EAOs, i.e. extensive coordination within the resistance. It should be recalled that EAOs and Peoples Defense Forces have been fighting alongside one another since May 2021 in more and more parts of the country.

As such, the military leadership has left its forces ever more prone as long lines of “dominoes” waiting to topple, one after the other. The placement of these dominoes is obvious enough to combatants on the ground. Myanmar’s geography emphasizes the imperatives of controlling the few paved, all-weather roads and bridges, together with the crossroads which link them, that make wider territorial control possible. A simple mapping of Operation 1027 shows that the NAB masterfully took key towns, bridges, and crossroads to prevent the military from regaining any initiative in northern Shan. Taking Hseni, a major crossroads town, immediately and blowing up the large bridge just south of it, was a masterstroke; as was the subsequent capture of the bridge west of Namkham connecting northern Shan with Kachin State. In combination with the immediate capture of the border town of Chin Shwe Haw, the NAB quickly demonstrated it was intent on full control of northern Shan, and then some. These actions left the junta struggling to retain both outposts and towns that are now isolated from even the possibility of reinforcement. It was telling that the junta made no major effort to keep these bridges, likely because of incompetence by the junta command and the lack of reserve forces.

The wider logic of Operation 1027 was strong but the NAB demonstrated exceptional prowess in terms of operational planning, execution, and messaging. The first two achievements of the NAB were supported by wide-ranging, escalating attacks on junta forces across the country since May 2021 while the third, as mentioned, highlights there is more national coherence to Myanmar’s resistance than the cynics ever countenanced. All three should be seen within the same vein of logic – that of a wider revolution. When the NAB calls for mass escalation across the country, catalyzed by Operation 1027 and supported by its member EAOs as needed, it is speaking the language of the Spring Revolution. It also directly counters the daft tendency of foreign journalists and diplomats to swallow the junta’s false equation that “the junta is collapsing” equals “Myanmar is fragmenting.” Moreover, Operation 1027 should be understood alongside simultaneous KIA successes in securing roads as well as NAB actions with PDFs in strategic parts of Sagaing and Magwe regions. From here, the rolling waves of junta collapse will quicken since they are already in progress.

As such, it is important to be clear about the preceding and ongoing context for Operation 1027 and subsequent events. The wider revolution has enjoyed major achievements. These include the emergence of widespread resistance in Sagaing and Magwe, proof that Bamar were willing to fight en masse and tenaciously so. That the junta had to take the drastic step of moving forces out of northern Shan to Karenni demonstrates that one of the country’s smallest states has achieved some of the most coherent, competent, and effective resistance, and this despite the violent displacement of a large proportion of the Karenni population. The KNU has been a stalwart force across the country’s southeast, steadily escalating attacks from the outskirts of Naypyitaw, across greater parts of Bago, to the towns spanning the Asian Highway to Myawaddy, and on down into southern Mon and Tanintharyi.

In Chin, tenacious resistance from the earliest days after the coup has left junta troops cooped up in urban garrisons since early-2022 aside from bloody, failed efforts to get large convoys up the foothills from northern Magwe or losing massive numbers of troops on forced marches from Hakha to Thantlang. The KIA has played a mentoring role for so many, both PDFs and EAOs, that its significance extends far beyond Kachin. Its strategic vision and ability to fight across such large areas is a bulwark for the entire revolution. In Sagaing, of the region’s 37 townships, at least 25 have been active for the resistance in any given month since late 2021. This is true for northern Magwe too, and increasingly so for a dozen townships in western and northern Mandalay over 2023. This resistance across the Bamar heartland – Sagaing, northern Magwe, and spreading across Mandalay – never slowed down despite relatively limited access to weaponry and over 60,000 dwellings burnt down by the junta and well over 800,000 civilians displaced. And so the list goes on across other parts of the country. Surely to the lament of any level-headed junta general, it all adds up!

The NAB deserves and will rightly receive a lot of credit for taking the bold, firm step of Operation 1027, but acknowledgement must also be given to the wider resistance. To the PDFs that started their armed struggle with nothing but muskets in 2021. To EAOs like the KNU, KIA, CNF and KNPP that have taken unfaltering steps since the beginning to stand on the right side of history by both fighting the junta and supporting new groups to form and mature. To the resistance’s political leaders, administrators, protest groups, fundraisers, and social service providers who will never get the same recognition as fighters but are as much part of the revolution as anybody. Cynics may see division and ‘fragmentation’ everywhere they look. But the degree of political dialogue and accommodation demonstrated by the resistance is historic and remarkable by any standard. Indeed, in the same way, most important for all has been the unwavering support of countless local communities to persevere despite over 32 months of junta atrocities.

This op-ed is not meant as rank bravado. The war is not over, but its trajectory has shifted steeply in favor of the resistance. What is necessary now, particularly for the international community (at least the parts that genuinely want to support the Myanmar people) is, at a minimum, to concede that the junta can be defeated outright and that such an outcome requires active preparation.

Moreover, there is a moral obligation to acknowledge that the shared sacrifices of the resistance can be a foundation for future reconciliation, stability, and dialogue. The rigors of a revolutionary war, what the NUG’s Acting President Duwa Lashi Lai called the ‘second war for independence’, will do more to bridge divides than another ‘transition’ – driven by a farcical peace process designed by the military alongside its self-serving constitution – ever could.

Prospects of future stability and reconciliation should not be taken for granted and certainly not as a given. But it does mean that the paternalistic cynicism that shades too much of the international community’s understanding of what is happening in Myanmar needs to be dropped. If other countries want to help, let them start by being more open-minded to the prospects for positive collective change rather than driven overwhelmingly by the fear of what might go wrong and the unhelpful, dogged insistence that Myanmar is fractured beyond repair. Myanmar’s future is not set in stone. The world owes the Myanmar people the benefit of the doubt given their collective determination and fortitude to win despite the barbarity of the junta. In multiple ways, this effort has been decades in the making and now it is becoming a reality. This should be all the more evident given the impetus created by Operation 1027. In such a dark, jaded world, surely the prospect of a genocidal junta collapsing is worth countenancing, preparing for, and, indeed, celebrating.

Matthew B. Arnold is an independent policy analyst. He has been researching Myanmar’s politics and governance since 2012.