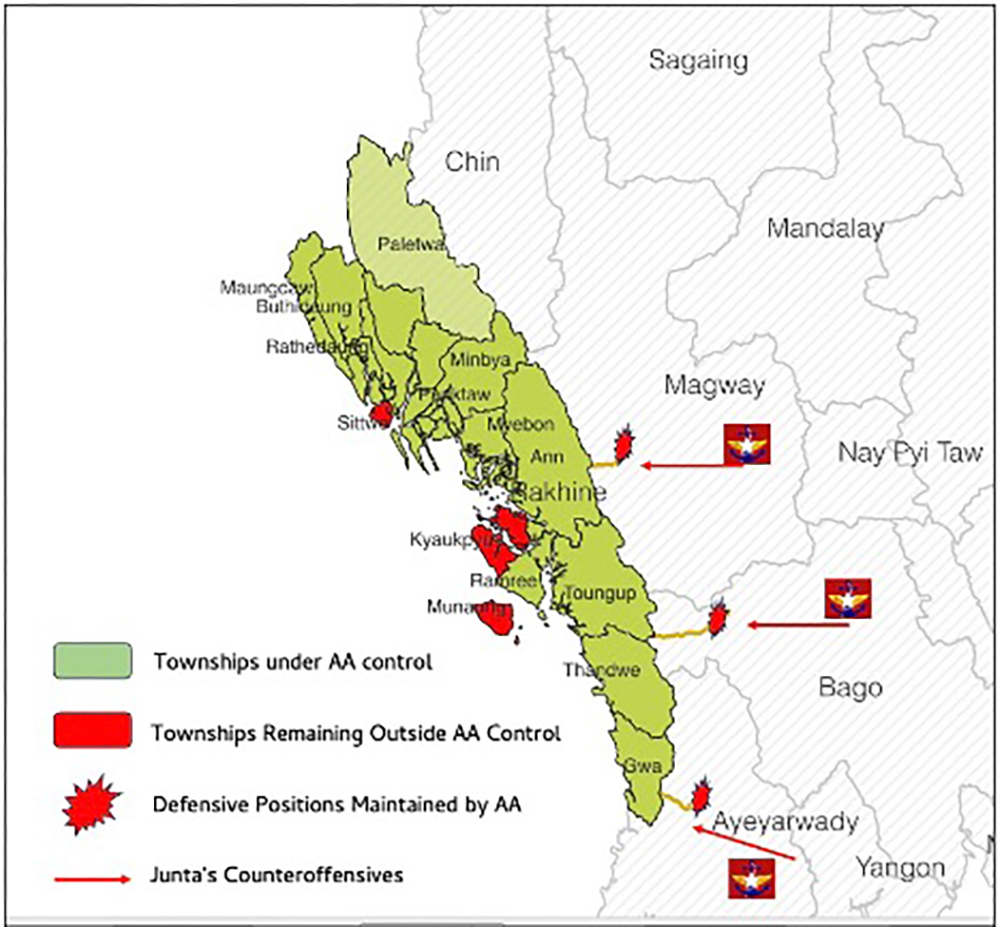

Arakan Army (AA) spokesman Khaing Thukha acknowledged at a recent press conference that heavy clashes persist in Rakhine State’s Kyaukphyu Township due to counteroffensives by the “terrorist” Myanmar military, which employs drones and aerial strikes. But he reiterated that the AA remains committed to its political objective of “liberating” all of Rakhine State, explicitly referencing the three townships still outside its control: Sittwe, Kyaukphyu, and Manaung.

Why, then, has the AA hitherto refrained from launching full-scale offensives against Sittwe and Kyaukphyu? This is due to three strategic calculations—China’s significant investments in Kyaukphyu, India’s investments in Sittwe, and the AA’s own priority of building local legitimacy and governance.

Kyaukphyu: The Chinese factor

Kyaukphyu hosts Chinese flagship projects including a deep-sea port and Special Economic Zone (SEZ) valued at US$1.3 billion, pipeline infrastructure worth $2.4 billion, and a $180 million power plant. In July 2024, South Korea’s POSCO International awarded a $523 million contract for the fourth phase of the Shwe Gas Field to China Offshore Oil Engineering there. That means thousands of Chinese workers are now deployed to support construction, and private Chinese security companies have been tasked with protecting Chinese personnel and infrastructure. Their presence reportedly includes the use of drones, electronic jammers, and mines around key facilities.

A full-scale AA offensive, then, risks causing collateral damage to the infrastructure and potential casualties among Chinese nationals and security forces, which could strain its longstanding relations with China. Even if the AA were to seize control of the town, it would remain vulnerable to naval strikes by the military.

Instead of a direct assault, the AA has therefore opted to besiege Kyaukphyu by encircling it with troops, applying pressure to compel Myanmar’s junta to withdraw through negotiation rather than destruction.

Sittwe: The Indian dimension

Sittwe, the state capital, is the site of significant Indian strategic investments, notably Sittwe Port and the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project (KMTTP). The port, built with an Indian grant worth approximately $120 million, was inaugurated in May 2023, when it received its first cargo shipment from Kolkata. The KMTTP envisions a trade corridor connecting India’s northeast to the Bay of Bengal, with shipping from Kolkata to Sittwe Port followed by inland transport up the Kaladan River to Paletwa in Chin State, which was captured by the AA in 2023, and then onward by road to Mizoram State. India initiated engagement with the AA following its capture of Paletwa and the townships along the Kaladan River, making India the second major power—after China—to establish direct dealings with the group.

In January 2025, Indian Ambassador Abhay Thakur inspected the Kaladan Project in Sittwe to review its progress and reaffirm India’s commitment to ensuring its timely completion, with operations scheduled to start in 2027. At a recent press conference, Khaing Thukha reaffirmed the AA’s commitment to facilitating India’s completion of the Kaladan project.

When the junta blocked commodity flows into Rakhine State, both the AA and local populations in the captured townships became heavily dependent on commodities—including essential medicines—imported from India’s Mizoram State. A direct assault on Sittwe would therefore risk damaging Indian infrastructure and straining relations between AA and India, which could prompt New Delhi to impose restrictions on this vital cross-border trade. It is this strategic consideration, the same as in Kyaukhpyu, that has led the AA to maintain a siege of Sittwe rather than attempt a full-scale offensive.

If the AA were to launch an offensive against Kyaukhpyu or Sittwe—let alone the island of Manaung—these towns would also likely face widespread devastation from junta airstrikes, drone operations, artillery shelling, and naval bombardments. According to an individual close to AA leaders, the group has drawn lessons from the situation in Bhamo. Since December 2024, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and allies including the AA have attempted to seize Bhamo, Kachin State’s second-largest city. But despite sustained assaults, they cannot manage to capture the town, which is meanwhile being devastated by relentless military bombardments. AA leaders are determined not to let Kyaukhpyu or Sittwe become another Bhamo.

Building legitimacy and governance

Another key strategic calculation of the AA has been to prioritize the establishment of political legitimacy and governance. Having secured control over the other 14 townships in Rakhine as well as Paletwa Township in Chin State, the group seeks to consolidate an administrative foundation capable of governing diverse ethnic communities. It has now been eight months since these areas fell under AA control, and the AA has faced significant criticism, particularly from the Rohingya and Chin communities.

Following the enactment of the AA’s National Defense Emergency Provision in March this year, which mandated forced conscription, both the Rohingya and Chin communities have increasingly voiced opposition to its governance. The AA has been accused of coercively recruiting Rohingya Muslims, and this month Rohingya communities further alleged that the AA was responsible for a massacre of 600 Rohingya civilians—an accusation that Khaing Thukha categorically denied.

Similar accusations have been made regarding the AA’s conduct in Chin State, particularly in Paletwa. Reports highlight arbitrary arrests, sexual violence, forced recruitment, and the deliberate displacement of indigenous Chin communities. Prominent Chin organizations—including the Global Khumi Organization, the Chin Human Rights Organization (CHRO), and the Chin Political Steering Committee (CPSC)—have repeatedly issued public statements condemning the AA and urging it to halt such practices.

This dual challenge of legitimacy and governance has complicated the AA’s consolidation efforts. Rather than pursuing immediate military offensives to capture the three remaining Rakhine townships, the AA has been forced to confront the more difficult task of winning local trust and providing credible governance. Such struggles are not unique to the AA: other ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), notably the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) in northern Shan State, face parallel challenges in administering ethnically diverse territories.

AA leaders seem to have calculated that without consolidating governance and establishing legitimacy, further offensives could overstretch their resources and undermine their capacity. Consequently, the AA has increasingly focused on delivering public services to the communities it administers.

Deterring junta counteroffensives

The AA appears to be maintaining a deterrence strategy aimed at preventing the military from reclaiming lost territory. On July 31, the junta declared a nationwide state of emergency, listing 63 townships that included all areas captured by the AA. And on Aug. 15, the junta’s Union Election Commission announced constituencies for its planned elections, incorporating these contested townships.

At a press conference, Khaing Thukha reaffirmed that the AA would neither return any captured township to the junta nor permit elections to be held in its controlled areas. To consolidate its hold and deter counteroffensives, the AA has focused on blocking military advances from three strategic corridors:

- Inthe Magway Region, along the Ann–Padan Road, a key route linking Rakhine and Magway

- Inthe Bago Region, along the Taungup–Pandaung Road connecting Rakhine and Bago

- Inthe Ayeyarwady Region, along the Gwa–Ngathaingchaung Road linking Rakhine and Ayeyarwady.

Meanwhile, the junta has intensified counteroffensives in Kyaukphyu and is reportedly preparing to extend operations to other contested areas, particularly Sittwe. Although the timing of a full-scale AA offensive in the remaining townships remains uncertain, the group appears to be waiting for either a negotiated military withdrawal or the launch of a nationwide campaign—often referred to as the “third wave”—by allied resistance forces, particularly the NUG.

According to a source with close ties to the AA leadership, this “third wave” is envisioned as a coordinated nationwide operation building on Operation 1027 (October 2023–January 2024) and the second wave of offensives (June–December 2024), both initiated by the Brotherhood Alliance of the AA, TNLA, and MNDAA.

For now, the AA seems intent on maintaining the status quo: defending captured areas from junta counterattacks, refraining from large-scale new offensives, and focusing on consolidating governance and legitimacy in its territories.

Joe Kumbun is the pseudonym of an independent political analyst.