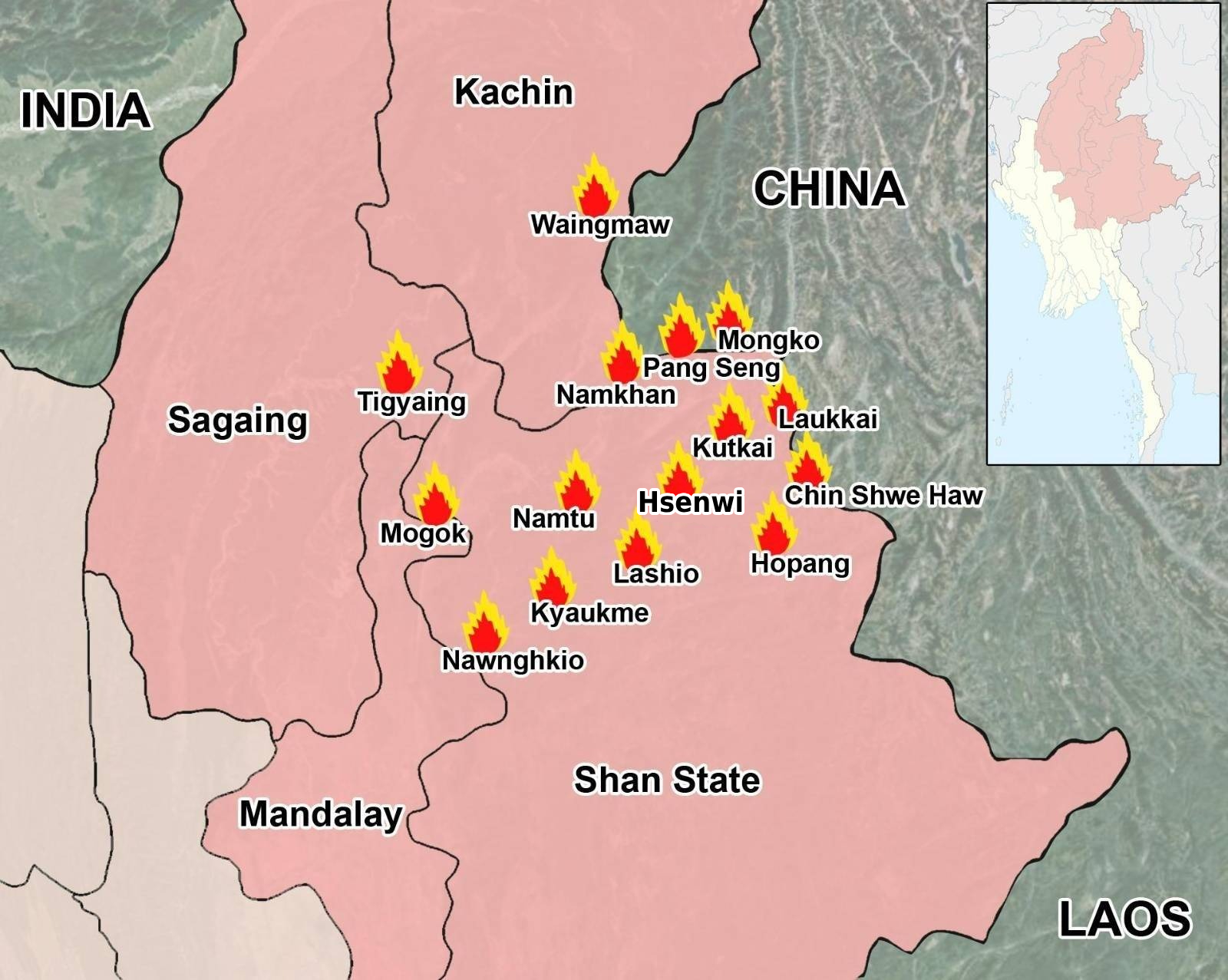

Is China finally turning its back on the ethnic armed groups across its border with Myanmar – and are they distancing themselves from their traditional benefactors in the Chinese security services? Coordinated attacks carried out by the Brotherhood Alliance – comprising the Kokang-based Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), Ta’ang National Liberation Army and Arakan Army – across northern Shan State which have led to the disruption of trade between China and Myanmar seem to indicate precisely that. And before what is termed “Operation1027” was launched by those three groups in late October, China issued arrest warrants for two leading members of the United Wa State Party and Army (UWSA), Chen Yanban, aka Bao Yanban, and Xiao Yanquan, aka He Chuntian. The Chinese have also reportedly detained Bao Junfeng, a deputy commander of the UWSA. He Chuntian is none other than the son-in-law of UWSP/UWSA supremo Bao Youxiang and Bao Junfeng is a nephew. Bao Yanban is a prominent businessman who operates casinos and scam compounds in the UWSA-controlled areas. All of them are accused of involvement in telecom fraud operations in areas near the Chinese border.

The UWSA is not a member of the Brotherhood Alliance and, after the attacks, declared its neutrality in the ongoing fighting. But the fact remains that the UWSA is the main supplier of weapons to the Alliance, and that those guns are of Chinese origin. Part of the seemingly confusing picture is also the Was’ close contacts with China’s security services which go back to the days when they formed the bulk of the fighting force of the now defunct Communist Party of Burma (CPB). Back in the 1960s and 1970s, the CPB received massive – and direct – support from China. That was never a secret. Chinese interactions with the UWSA may not be that overt and guns are provided mostly at “friendship prices”. But, even so, the UWSA is equipped with more and better Chinese military hardware than the CPB ever was.

The UWSA has not passed on the most sophisticated of its supplies from China, such as surface-to-air missiles, but the Brotherhood Alliance apparently had enough guns and ammunition to be able to carry out their series of attacks, which seem to have been astonishingly successful. China may not have played any part in Operation1027, but it is hard to believe that its well-connected security services were unaware of what was being planned and it appears that China did nothing to try to stop it. In short, the situation appears utterly confusing and completely devoid of logic.

But the answer to speculation by outside observers about a major policy shift is no. Beijing has not changed the nature of its relationship with the ethnic armed organizations in the north, and these are not turning against China. Beijing’s long-term objectives remain the same: to exploit Myanmar’s natural resources and, most importantly, to secure the so-called China-Myanmar Economic Corridor which gives it strategic access to the Indian Ocean. To achieve those goals, China has always played all sides in Myanmar’s internal conflicts and it is therefore not, it should be remembered, in China’s interest to see the emergence of a strong, peaceful, democratic and federal Myanmar.

As long as Myanmar is weak, China can play official games of being a “friendly neighbor” and “peacemaker” and, at the same time, use a carrot-and-stick approach to whatever government is in power: trade coupled with investment on the one hand and indirect support for the ethnic armed organizations on the other. If Myanmar ever became exactly that – strong, peaceful, democratic and federal – China would be the first to lose. The leverage China has today inside Myanmar would be gone. But then China does not want to see the situation get totally out of hand either, because that would mean serious instability in the frontier areas and, most likely, an unwanted flood of refugees across its border.

But China’s multifaceted – to use a euphemism – approach to Myanmar and its many internal conflicts has also created a number of problems which don’t stop at the common border. After the collapse of the CPB in 1989, which was caused by a mutiny among the predominantly Wa rank and file of its once powerful army, and the formation of the UWSA, a peace deal was agreed (but not signed) with the then junta in power in Myanmar, the State Law and Order Restoration Council. Part of the deal was that CPB mutineers, now UWSA and three other former communist forces turned ethnic armies, would be allowed to retain their armed forces and maintain control over their respective areas in exchange for not entering into any alliances with other ethnic armed organizations in Myanmar. They were also allowed to engage in any kind of business to sustain themselves – and that became a lucrative trade in narcotics, first opium and its derivative heroin and later methamphetamine.

Within a couple of years of the mutiny, Myanmar’s illicit drug production had skyrocketed – and drugs began to spill over into China. The southern province of Yunnan, which borders Myanmar, was especially hard-hit. Heroin was everywhere, and local drug lords in China began establishing their own fiefdoms, including the gang that took over Pingyuan, a town in the south. By 1992, Pingyuan had become a “country within the country”, giving safe haven to outlaws and bandits from across China. It became a matter of internal security, and thousands of heavily armed troops, supported by armor, eventually moved in and recaptured Pingyuan. The drug lords were mostly ethnic Yunnanese Muslims known as Hui in China and Panthay in Myanmar, and they had extensive business contacts throughout the Golden Triangle, including former CPB areas.

Another push against drug trafficking in Yunnan was launched in mid-1994. It followed the arrest of Yang Muxian, a younger brother of then Kokang chieftain Yang Muliang, a former CPB commander who after the 1989 mutiny had founded the MNDAA, which then had a ceasefire agreement with the Myanmar military. Yang Muxian was charged with smuggling hundreds of kilograms of heroin into Yunnan and was executed in Kunming in October 1994 along with 16 accomplices. No Was were charged or arrested at that time, but Bao Youxiang and other UWSA leaders were called several times to Kunming and told to make certain that drugs did not enter China. The situation was brought under control and China could carry on its relationship with the former CPB forces – the UWSA, the MNDAA, a unit based in Mong La in eastern Shan State, and a smaller group in Kachin State – in a frictionless manner.

This time the rough and tumble has been caused not by drugs but by telecom fraud that is being carried out in areas controlled by ethnic armed organizations across the border in Myanmar. IT specialists from not only Thailand and the Indian subcontinent but also far-away countries like Uganda and Ethiopia have been tricked or forced into running the operations. The main targets for the scams have been people and institutions in China, and Chinese officials believe that capital outflows as a result of the scams amount to at least US$40 billion. It was clear that the Chinese authorities had to take action. And they did.

As was the case after the crackdown on drug trafficking in the 1990s, it will take some time for the Chinese to reestablish smooth relations with the ethnic armed organizations in Myanmar’s north. Despite the flow of drugs, China needed those groups in the 1990s for the same reason as it needs them today: to secure a geostrategic foothold inside Myanmar. The fighting may have brought bilateral, cross-border trade to a standstill, but that is unlikely to last for much longer. The current fighting in the north may even work to China’s advantage. The Chinese can now play another of the many cards they have up their sleeves: that of friendly, neighborly peacemakers. And China may, once again, be the winner.