Last week, news of the heavy defeat suffered by the Myanmar military in Laukkai, the capital of the Kokang Self-Administered Zone in northern Shan State, eclipsed the country’s Jan. 4 Independence Day celebrations.

A day earlier, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), an ethnic armed organization that is fighting the military regime, claimed to have shot down a military chopper, believed to be a Russian-made Mi-17, killing all military personnel on board, in Kachin State, northern Myanmar.

Myanmar netizens that night enjoyed “roasted bird” to celebrate the downed helicopter on social media. Speculation was rife that the helicopter, which was on a routine supply mission, was shot down by a Chinese-manufactured FN-6 man-portable air defense system (MANPAD). The KIA did not comment on the weapon used. There have been repeated calls from those opposed to the junta that the Myanmar resistance be provided with a ground-to-air defense system capable of shooting down helicopter gunships, as the military has been unrelenting in its application of air power against resistance forces and civilian populations.

It was not the first time we learned that a helicopter had been downed in Kachin State.

In May 2021, the KIA claimed to have shot down a military helicopter during a clash in Momauk Township, Kachin State.

On Nov. 11, two weeks after the Brotherhood Alliance of ethnic armed organizations launched their Operation 1027 against the regime in northern Shan State, ethnic Karenni resistance groups who had launched their own version of the offensive—Operation 1111—claimed to have shot down a regime fighter jet, a Chinese-made K-8 W, during a clash with regime forces in Karenni (Kayah) State. A week later the ethnic resistance groups arrested Major Khaing Thant Moe, one of two junta pilots who ejected from the aircraft.

Then last week we covered the news of Laukkai falling into the hands of Kokang insurgents, as many in the newsroom had predicted.

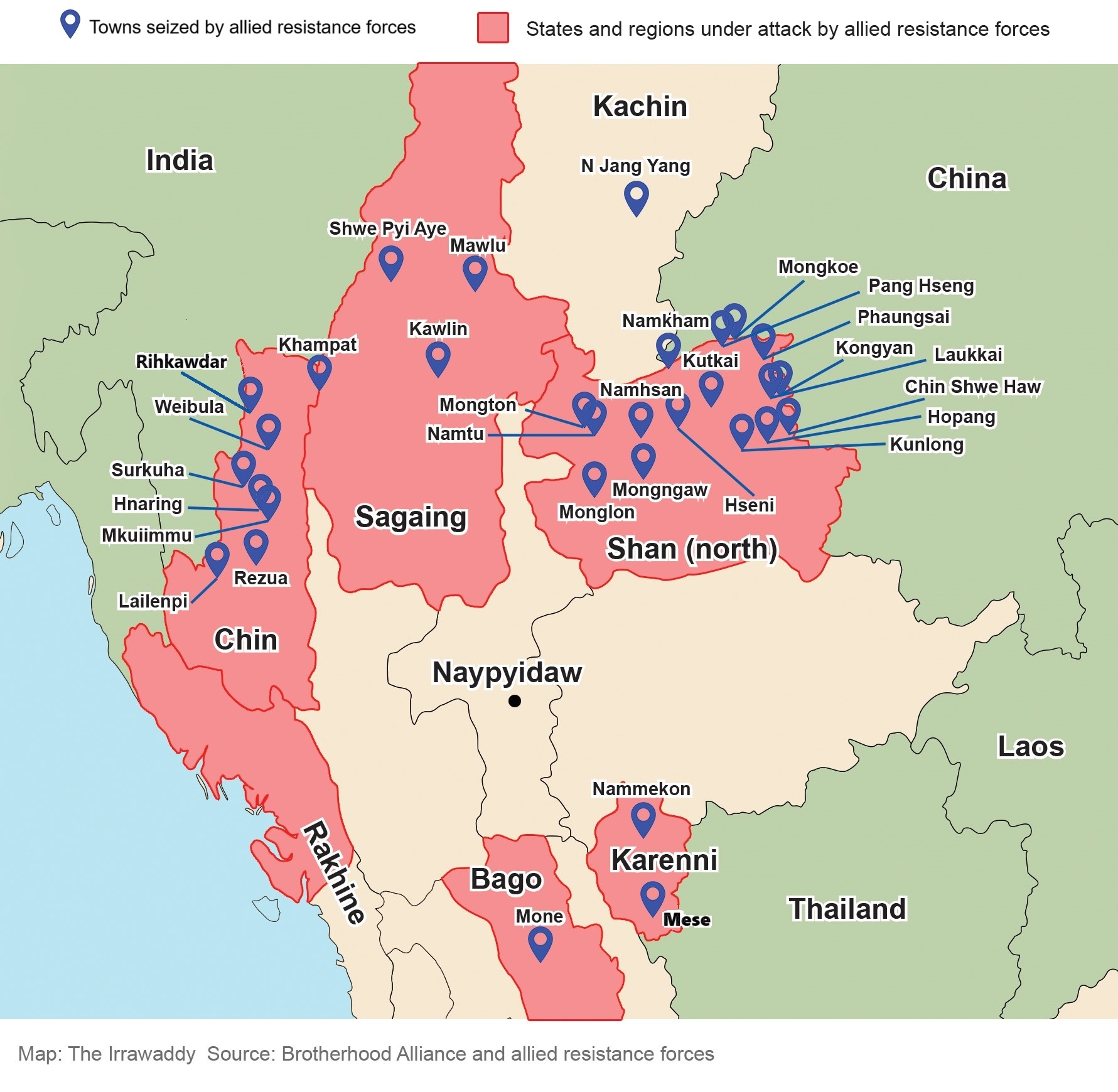

Since the Brotherhood Alliance—which comprises the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) and Arakan Army (AA)—along with several resistance groups, launched Operation 1027 on Oct. 27, they have seized tanks, armored vehicles, multi-rocket launchers, howitzers, and thousands of rounds of ammunition and other weapons. A division commander, Brigadier General Min Min Tun, was captured by the TNLA in Namhsan in December, becoming the highest-ranking regime military officer captured so far. The resistance forces have seized over 400 military outposts, both small and large, in northern Shan State and Rakhine State, and taken control of five China-Myanmar border trade zones. In northern Shan State alone, 16 towns have been captured by the alliance as of Jan. 8.

The fall of Laukkai isn’t just the biggest setback for the junta since the 2021 coup—it is the biggest military defeat in the modern history of the Tatmadaw, as Myanmar’s military is known.

In Laukkai, over 2,100 regime troops, six brigadier generals, 228 other officers, and over 1,600 family members of military personnel have surrendered to the MNDAA in the Kokang zone. The Laukkai Regional Operations Command (ROC) was overrun, becoming the first Regional Operations Command to fall. The total number of troops to surrender was 3,990. The MNDAA declared the whole of Kokang a “regime-free zone”, saying it marked the beginning of the end of the dictatorship.

In just over 70 days since the start of Operation 1027 it is estimated that over 4,000 military personnel have surrendered.

The order for the Laukkai command to surrender came from Naypyitaw, but it remains unclear who gave the final order. Was it junta chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing or his deputy, Vice Senior General Soe Win, who is commander-in-chief of the army? The two generals do not like each other. It was not a happy day for the top commanders in Naypyitaw.

The fall of Laukkai isn’t just the biggest setback for the junta since the 2021 coup—it is the biggest military defeat in the modern history of the Tatmadaw, as Myanmar’s military is known.

While there is little public sympathy for the military, it is being whispered in Yangon that China’s “proxy ethnic armies”, meaning the Brotherhood Alliance, have defeated the regime’s troops. Indeed, the MNDAA has long enjoyed China’s friendship.

Having said that, anyone wanting to attack the regime in Naypyitaw would have the unconditional support of most of the population in Myanmar.

Military analysts and defecting army officers say the military’s troops lack the will to fight and would rather raise the white flag.

The regime has sophisticated weapons and air power but so far, the junta has not yet been able to send in reinforcements or retake its bases. However, the brutal commanders keep bombing innocent civilians and villages.

Looking at the recent battles in northern Shan State, it’s easy to see that Myanmar’s military is in serious decline.

When resistance troops attacked an outpost in Nawnghkio Township’s Thanbo village, in Shan State, they found that neither the commander of the outpost nor many of the troops he was assigned to lead had any combat experience. They found a wide range of uniforms and badges on those under his command, showing that the junta’s military had sent staff from its medical services, as well as communications, electrical and engineering units—even from its fire department and weapons factories—to the frontline. The junta’s “cocktail army” is doomed to failure.

The resistance offensive has spread to upper Sagaing Region and Karenni, Chin and Rakhine states. The AA began attacks on regime forces in Rakhine State on Nov. 13 and fighting continues across northern Rakhine and in Paletwa Township in southern Chin State. They have seized towns and attacked junta bases. In Rakhine, the AA says it has seized more than 140 junta bases and outposts. On Jan. 7, over 100 Myanmar soldiers surrendered in the state’s Mrauk-U and 200 surrendered in Kyauktaw Township.

However, Karen and People’s Defense Forces in the south lack ammunition and coordination, and have not been able to capture many strategic positions in Karen State or areas close to Naypyitaw. (They say they need more ammunition, drones and weapons seized in the north so that they can consolidate and push further.)

The junta continues to deploy assets including helicopter gunships and jet fighters to attack and intimidate populations in Sagaing and Magwe regions and Karen and Karenni states.

Resistance forces in Karenni have control of 80 percent of the state bordering Thailand’s Mae Hong Song province. Karenni is also close to Naypyitaw. Will resistance forces there push further?

There has been no announcement yet on a proposed end date for Operation 1027, but it seems unlikely to be halted at this point.

The insurgents in the north continue to consolidate the capture of strategic towns, cities and border trade routes. Analysts say the next target is Lashio, the largest city in northern Shan State, and the main foothold of junta control in the region.

In addition to a lack of sympathy and support from the public, the military faces serious recruitment problems, internal resentment, desertions and low morale.

Like an old truck with a flat tire barreling out of control down a steep hill, the writing is clearly on the wall for the military—or, as its own citizens now mockingly refer to it, the “White Flag Tatmadaw”.