I have no crystal ball with which to predict the path our country will take in the second half of the 21st century. But recently I’ve found myself contemplating a historical pattern that could offer a guide to what the coming decades hold for Myanmar.

According to my hypothesis, we people in Myanmar are riding on history’s roller coaster. While it’s exhilarating at times, it’s a ride that can cause serious anxiety, too!

To anticipate what’s in store for Myanmar in the decades leading up to 2100, the past might serve as a useful guide.

Let me start with the 19th century. When the British officially colonized all of Myanmar on Jan. 1, 1886, after their final seizure of the Mandalay Palace and the forced abdication of King Thibaw on Nov. 28, 1885, no one in the country would have imagined they would be living under colonial rule for the next 60 years.

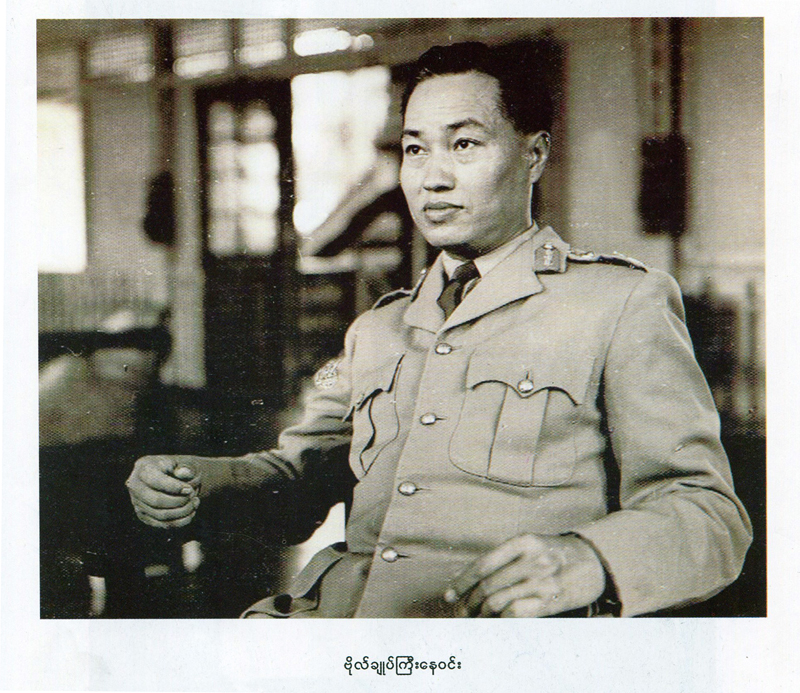

And, likewise, let’s look at the 20th century. When General Ne Win was sworn in as the premier of the country’s caretaker government on Oct. 27, 1958, no one here dreamed their country was destined to be ruled by army generals for almost the next 60 years.

Looking back at our country’s history over the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries, I’ve discovered a cycle that follows a 60-10-60 pattern: Over the past 130 years, from 1886 to 2016, Myanmar endured the two unwanted political trends of imperialism and authoritarianism (more specifically, military authoritarianism).

The British ruled the country from 1886 to 1948—a period of 62 years. The military generals held sway for 58 years—from 1958, when the late dictator Gen. Ne Win introduced military rule to the country, until 2016, when the succession of generals came to an end and a political party managed to form a government for the first time since the 1960 election.

Between these two periods, there was more or less a decade-long interval from 1948 to 1958 (we could include in this period the two years from 1960 to 1962), which saw a parliamentary democratic system led by the country’s first post-independence premier, U Nu. Either way, it’s roughly a decade.

When we focus on decades, individual leaders and their policies tend to shape our view; but centuries are defined by events and trends. In the 19th and 20th centuries, our country—like many others around the world—was dominated by the political trend of colonialism. And when we look at the 20th and early 21st centuries, we see military authoritarianism as the main force.

Both these political trends had a similar effect: they disrupted the country’s ability to remake itself.

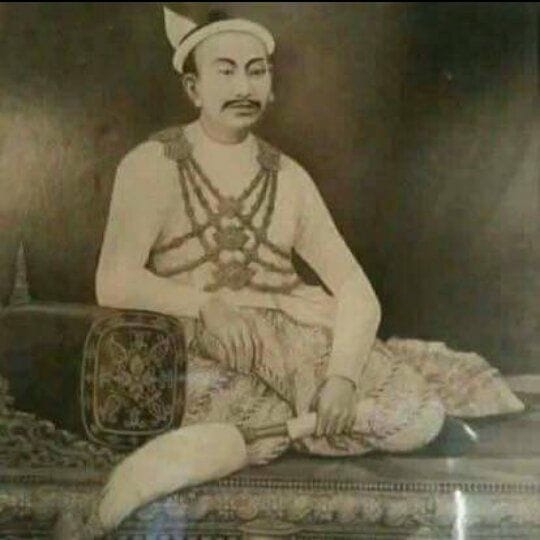

When the British staged the Second Anglo-Burmese War in 1852 to colonize the country, King Mindon, one of the most revered and popular kings in Myanmar’s history, was preparing to remake the country. His reign (1853-1878) was a period of modernization in which, with the help of his progressive princes and ministers, the king tried to catch up with the modern world. But his attempts at remaking the country were ultimately thwarted due to the global rise of imperialism.

After the country gained independence in 1948, Myanmar got its second chance to remake itself. The country’s leadership tried to do just this, and the period under U Nu from 1948 to 1958 is now considered a golden age for the country, marked by freedom and rights for citizens, and one of the most vibrant economies in Asia. But this second attempt, too, was disrupted by the imposition of military rule by generals citing the danger of political instability due to the civil war.

The generals’ rule would ensure the country would not get another chance at reinvention until 2016.

Looking back over the 130 years from 1886 to 2016, an approximate pattern emerges: 60-10-60.

Now we have a third chance to remake the country, after the previous military regime decided to loosen its grip on power in 2011 and its successor, a nominally civilian government led by U Thein Sein, transferred power to the elected government led by the National League for Democracy in 2016.

Electorally, however, we don’t need to count the five-year term (2011-2016) of general-turned-President U Thein Sein, though his government opened up the country to some extent; this was not a radical democratic reform and his government was formed as the result of a “manipulated” election that most pro-democracy parties, including the NLD and the main ethnic parties, boycotted. So, I would say the third chance to remake the country really started in 2016, after the winners of the 2015 vote managed to form an elected government for the first time in 58 years.

After missing its first and second chances to start anew in the 19th and 20th centuries, the country has a third, in the 21st century! One chance per century.

I see this third chance as resembling the post-independence period between 1948 and 1958. As during that period, the country is now dealing with the ongoing civil war—though now with even more armed groups—as well as the Rohingya crisis, which has put the country in an unprecedented dire situation and under mounting international pressure, and the failure (so far, at least) of the civilian government and the military leadership to achieve reconciliation. No one knows whether these issues will doom this third chance.

If we fail again, Myanmar is unlikely to get another chance to remake itself this century.

I am sure no one in Myanmar wants to see this rare chance slip away again. If it does, the pattern is likely to be 60-10-60-10-60, with the last “60” being an era like those under imperialism and authoritarianism, from roughly 2026 to the 2080s or ’90s. That will be towards the end of this century.

None of us wants this pattern to repeat; we want this vicious cycle to finally end. This time, history must not be allowed to repeat. The pattern the people of Myanmar wish to see is: 60-10-60-10 + eternity, or “colonialism—chance to remake the country—military rule—chance to remake the country—established democratic society”.

For now, no one can say for sure whether this third and last chance will be disrupted, as in the 19th and 20th centuries, given the fragility of the current political situation.

Almost everyone—including the leaders of the country, as well as observers of Myanmar and the global community—regard this period in Myanmar’s history as a democratic transition. They’re not wrong.

But I believe this period is more critical to Myanmar than a democratic transition might be in another country. This is a “do or die” transition in which Myanmar has an opportunity to finally break out of its old political pattern. Myanmar can’t afford to miss this third and final chance. If it does, it will truly be a failed state, and we may never be able to make a comeback, as a people or as a nation.

I think this is more than just an interesting time. We, the people of Myanmar, indeed seem to be riding a roller coaster. It may be both thrilling and frightening—but the most important thing is getting off the ride safely.