The Myanmar regime-controlled Central Bank of Myanmar (CBM) had more than US$6.8 billion in foreign reserves as of March this year in 14 overseas banks in Asia, Europe and the US, according to a CBM document seen by The Irrawaddy. Among the 14, nine Singaporean banks held more than $4.5 billion—more than half of Myanmar’s total foreign reserves.

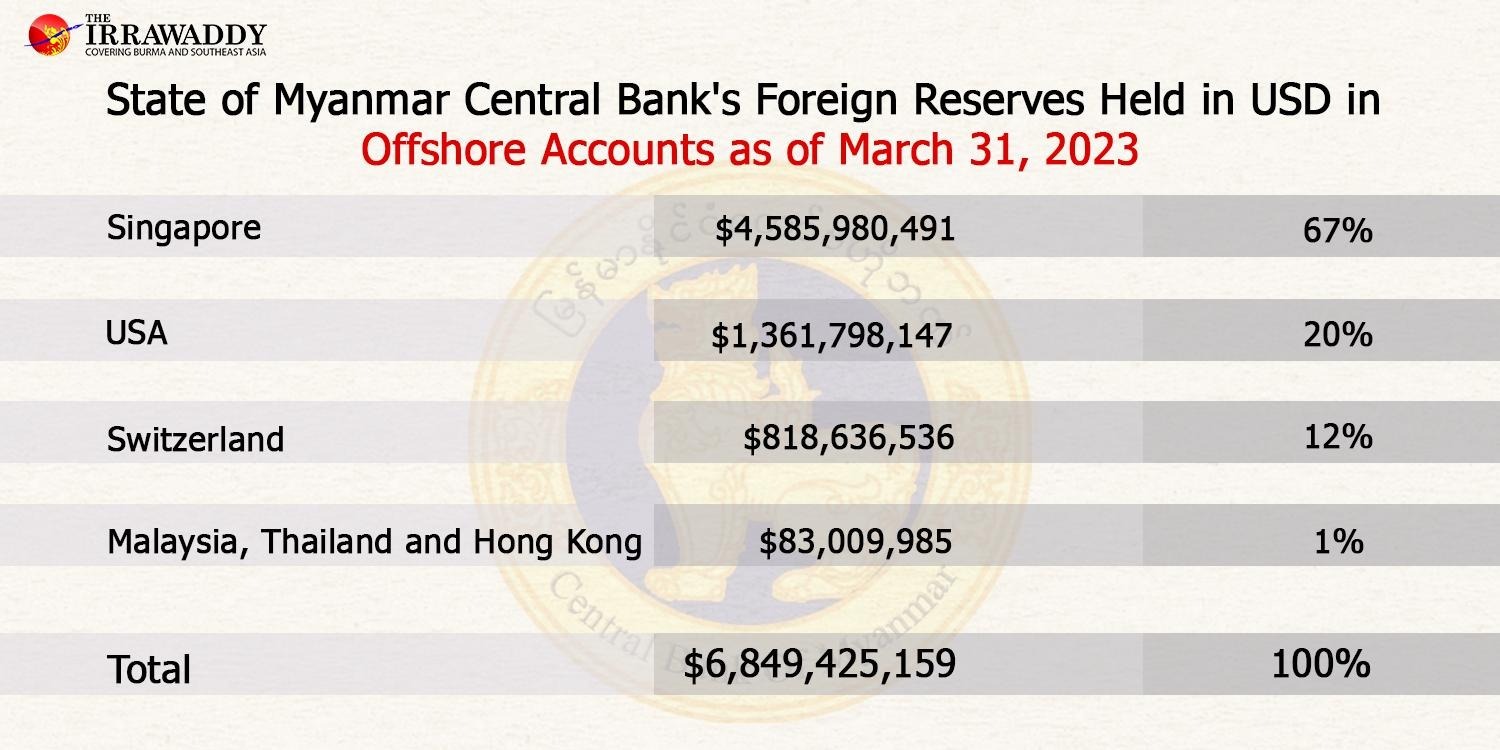

According to the document, Myanmar’s foreign reserves of $6,849,425,159 were held at banks in the US, Switzerland, Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand as of March 31.

The nine institutions listed as Singapore banks—DBS, UOB, OCBC, SMBC, May Bank (Singapore), Mizuho (Yangon branch), CIMB, MUFG and SCB—held a total of $4,585,980,491, or 67 percent of Myanmar’s total foreign reserves.

The second-largest portion was held by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRB NY) in the US (20 percent) while Switzerland’s Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in Basel held 12 percent. Bank of China (BOC) in Hong Kong, May Bank (Malaysia) and Thailand’s Exim Bank held the remaining 1 percent.

In the document, the CBM claimed that the foreign reserves had remained relatively stable since July 2022, though reserves held at FRB NY were declining due to interest payments to the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

The CBM said it had around $4.657 billion in hand as of March 31, excluding capital held on behalf of banks, and funds owed to the International Monetary Fund. As a result, it said, “there are FX reserves for only three months vs. imports.”

This means the CBM had foreign reserves to cover imports for April, May and June. The status of the bank’s current reserves in hand is unknown as Myanmar is experiencing serious inflation, with the value of the country’s currency, the kyat, deteriorating against the dollar daily. The market exchange rate is now approaching 4,000 kyats to the greenback.

With his regime starved of hard currency due to economic mismanagement and international sanctions imposed on it for killing opponents of its rule, the issue of whether Myanmar junta chief Min Aung Hlaing still has access to the more than $6 billion in foreign reserves Myanmar keeps in international banks is an important one.

A political analyst told The Irrawaddy that, in theory, the junta can still withdraw the reserves as the CBM is not sanctioned.

“But even if there are no sanctions, the banks can decline their customers’ business,” he said.

He explained that such a refusal by the banks would have the same effect as sanctions. “Foreign banks now see that doing business with the junta puts their reputations at risk, and if they stop [doing business with the regime], it will impact the junta,” he said.

The biggest financial blow to the junta so far came in June, when the US sanctioned two Myanmar state-owned banks—Myanma Foreign Trade Bank (MFTB) and Myanma Investment and Commercial Bank (MICB). They primarily function as foreign-currency exchanges and enable the conversion of kyats to US dollars and euros, and the reverse.

This month, a Bangladeshi state-owned bank at the center of the country’s trade with Myanmar froze the accounts of MFTB and MICB, which together had at least $1.1 million deposited at the bank.

Following the US sanctions on the two Myanmar banks, Singapore’s UOB—known as the offshore bank of choice for Myanmar’s generals—told Myanmar banks early this month that it will cut ties with them by Sept. 1, including Visa and Mastercard transactions by Myanmar individuals and banks, limiting their transactions to those between UOB accounts. However, it’s not clear if UOB has stopped working with the CBM.

Of all the banks in Singapore, the CBM seems to view UOB as the most reliable, moving $350 million to UOB from DBS and OCBC at the end of March. The CBM document viewed by The Irrawaddy explains that the reason behind the movement was “to help with liquidity and due to the fact that UOB have been the most ‘cooperative’ in helping CBM through periods of international sanctions.” As of March 31, UOB held $625 million for the CBM.

The US has reportedly asked all relevant stakeholders whether it would be best to target the regime-controlled Myanmar Economic Bank (MEB) or the CBM. The US sanctioned the Russian central bank in 2022, freezing its assets held in US financial institutions. The move also means that financial institutions outside the US that hold dollars for the bank cannot move them.

“The US should do it [target the CBM]; it is no good to let them off the hook. Whether the US decides to do it or not, it will have the same effect as imposing sanctions if the private banks stop doing business with the junta,” the analyst said.

While the 14 banks were still working with the regime’s CBM as of March 31, some other banks have declined to offer their services to the junta.

The CBM document said “the termination of USD outflow by JPM [JP Morgan] has created significant problems for the CBM. USD services stopped on 1 April 2023.”

It also said Deutsche Bank had closed its correspondent banking relationship with the CBM, without saying when.

The amount of money deposited in JPM and Deutsche Bank is unknown.

U Tin Tun Naing, the planning, finance and investment minister of Myanmar’s parallel National Unity Government (NUG), told The Irrawaddy that the NUG’s Interim Central Bank of Myanmar is also aware of the junta’s attempts to abuse the country’s foreign reserves abroad, and to utilize the Central Bank’s accounts, Myanmar Economic Bank, and potentially some of the private banks to subvert sanctions.

“We have been engaging the central banks and monetary authorities of key countries to push for stronger action against the SAC’s abuse of the country’s finances, and we believe they will realize it’s the right thing to do, on behalf of the people of Myanmar,” he said. The SAC, or State Administration Council, is the regime’s governing body.

The minister said he was aware that there are also many concerns about the effectiveness of sanctions, and that it was tempting to judge them by past experience in Myanmar, referring to the ineffectiveness of past international sanctions against previous military regimes.

But, he said, this is not the right frame in which to view today’s situation, because the current junta is much more dependent on international financial flows and supply chains than its predecessors. He said the impact of sanctions should be measured by every dollar denied to it, which it would otherwise be using to commit violence against an entire country.

“We have already seen the significant impact of current sanctions on the junta, creating significant problems in their ability to tap foreign reserves, or move funds around the world to fund their war,” he said.