The end of March marks the 60th anniversary of the first attempt to forge unity among Myanmar’s various Shan resistance forces. On March 25, 1964, representatives of the Shan State Independence Army (SSIA), the Shan National United Front (SNUF) and the Kokang Revolutionary Force (KRF) met at a secret hideout in the northern Thai city of Chiang Mai and decided to form the Shan State Army (SSA). The decision was made public in a village inside Shan State on April 24 – the official date of the founding of the SSA.

It looked promising. The SSA’s War Council was headed by Sao Nang Hearn Hkam, the Mahadevi of Yawnghwe and widow of Myanmar’s first president, Sao Shwe Thaik. She was also a well-known politician in her own right, having been an MP representing her home state Hsenwi and an outspoken proponent for federalism – which was abolished when General Ne Win seized power in a coup on March 2, 1962. That was also when one of her sons, 17-year-old Sai Myee, was killed and Sao Shwe Thaik was arrested in their home in Yangon. The former president died in jail in November of that year, presumed extrajudicially executed. Chao Tzang Yawnghwe, a young well-known academic and another of Sao Nang Hearn Hkam’s and Sao Shwe Thaik’s sons, became the SSA’s main theoretician.

But despite such credentials, it was a diverse gathering of groups with different motives and agendas. And not all Shan resistance forces joined the new army. The Shan National Army (SNA), a local resistance force in Kengtung, did not join and nor did Noom Suk Harn (‘the Young Brave Warriors’), the oldest of the Shan armies. The SNA, set up in 1961 by a former monk called Sao Ngar Hkam, or U Gondara, had its power base among the Kengtung Shan, who often consider themselves to be different from other Shans. Noom Suk Harn was formed in 1958 by Sao Noi (or Saw Yanda), a Yunnan-born, rural warlord who managed to get some Shan university students to join him. But they soon fell out with Sao Noi and, in 1960, established the SSIA. The SNUF was not an armed force, but a forum set up with the aim of uniting the different Shan armies at the time. It was led by Moh Heng, who, depending on the romanization of his name, was also known as Kwon Zerng or Korn Zurng. He had once been allied with the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) and, in 1956, broken away and formed his own Shan State Communist Party. The KRF was founded in 1963 and had, as the name suggests, its base in Kokang, an area in northeastern Shan State which is populated by ethnic Chinese. Its leader, Jimmy Yang (Yang Zhensheng or Yang Kyin-sein), was a former MP for Kokang and founder of the East Burma Bank.

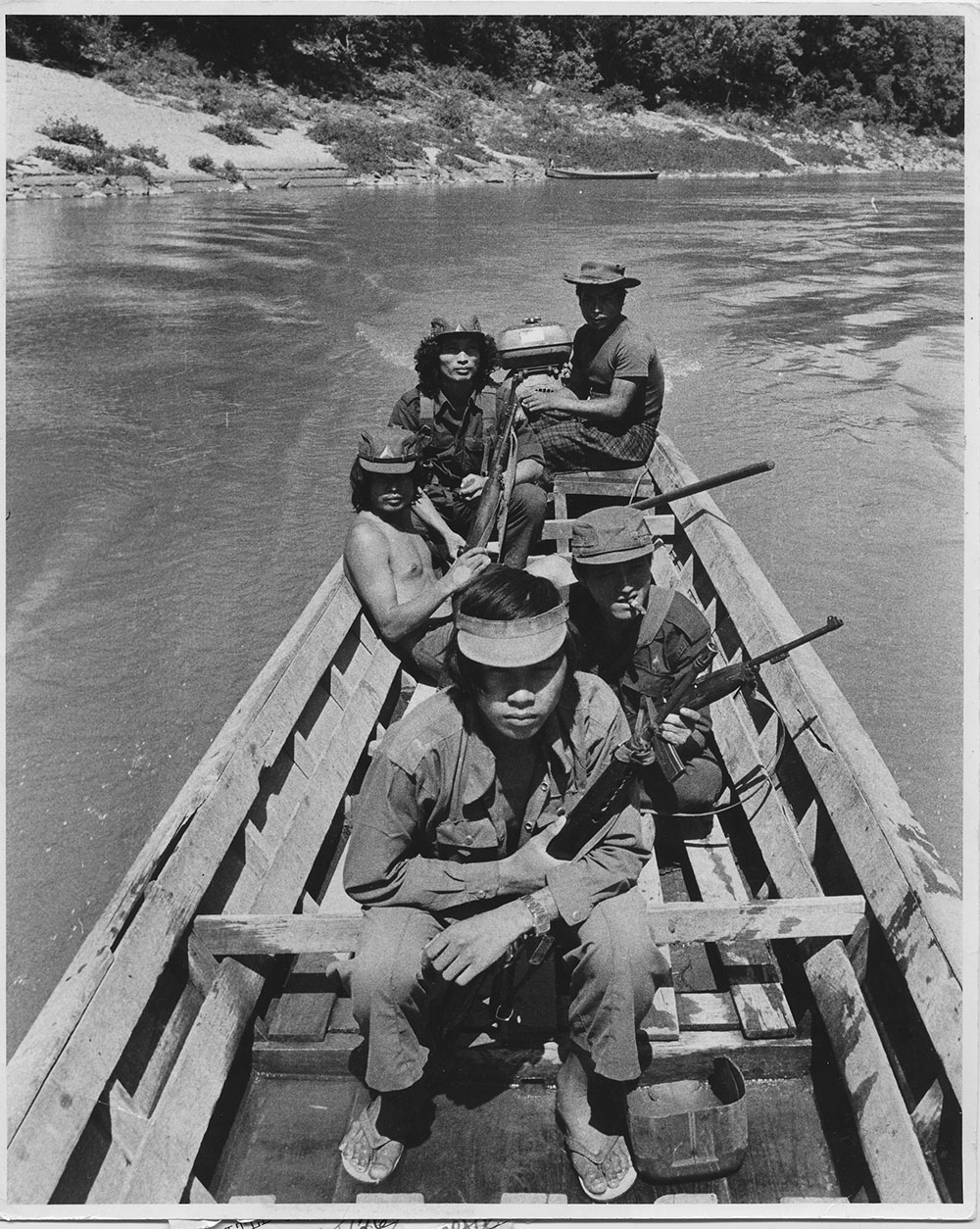

From the very beginning, regionalism was a major issue. The SNA held court in eastern Shan State, remnants of Noom Suk Harn were still active along the Thai border opposite Chiang Dao, and Jimmy Yang established a close relationship with the nationalist Chinese Kuomintang forces that had retreated into Shan State after being defeated by Mao Zedong’s communists in 1949. The other major problem facing the Shan resistance was the fact that the area they operated in also happened to be the so-called Golden Triangle, where opium politics became a dominant as well as divisive factor.

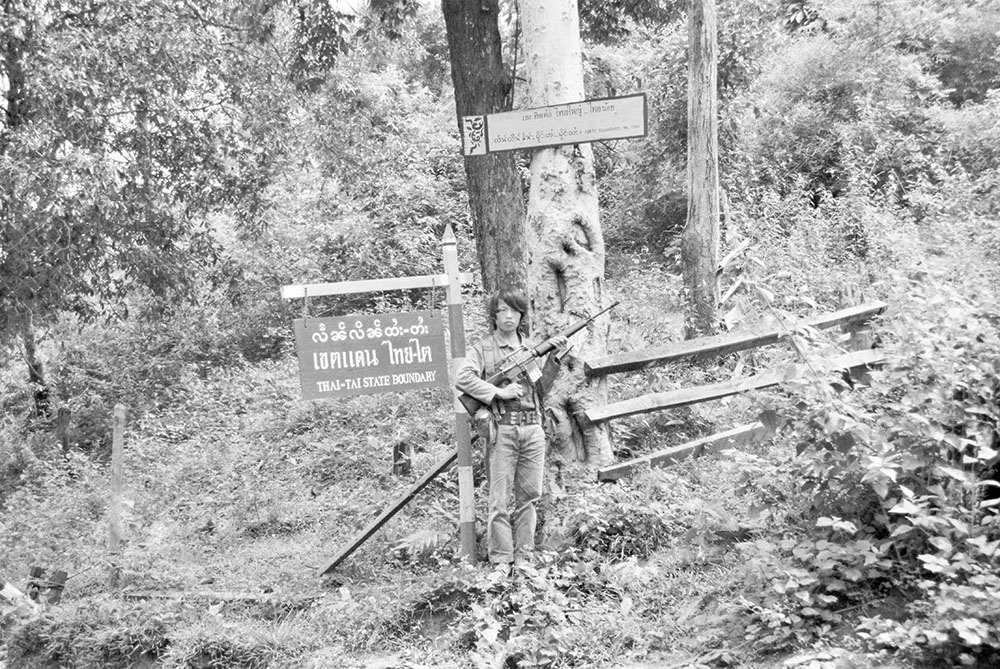

After the loss of the KRF, the next faction to break away from the SSA was its third brigade led by Moh Heng. Supported by the Kuomintang, he set up his own Shan United Revolutionary Army (SURA) on January 20, 1969 and established a base at Pieng Luang on the Thai-Shan border northwest of Chiang Dao. Unlike the SSA, which was mainly a mobile guerrilla force, the SURA firmly controlled Pieng Luang and had permanent camps just across the border, and that enabled Moh Heng to attract Shan intellectuals who could run schools and printing presses inside his area. But the SURA’s presence inside Shan State was limited, and it hardly ever clashed with the Myanmar army. On the other hand, the SURA became the Kuomintang’s operating arm inside the Golden Triangle and its mule convoys carried opium down to laboratories on the Thai border, where the raw material was refined into heroin. As a result, Pieng Luang grew into a small town and became one of the most prosperous settlements on the Thai-Shan border.

The proliferation of groups, shifting alliances, and the wealth that could be generated through the opium trade threw Shan State into a cockpit of chaos and anarchy, which got worse over the years. And even the Myanmar military decided to jump on the opium bandwagon. There was not enough money in central coffers to sustain an effective counter-insurgency campaign, and the government was also tied up with political and economic problems closer to home. To fight the rebels, the military had in 1963 authorized the setting up of local, home-guard armies called Ka Kwe Ye (KKY; ‘defense’) – and these militias were given the right to use all government-controlled roads and towns in Shan State for opium trafficking in exchange for combating the rebels. By trading in opium, the military hoped that the KKY home guards would be self-supporting. Lo Hsing-han, the commander of Kokang KKY, and Zhang Qifu alias Khun Sa of Loi Maw KKY were among those who became rich on the deal.

That, however, did not solve the problems the government had with counter-insurgency finance, and the situation was getting out of control. The KKY militias were disbanded in January 1973, but that led only to even more confusion. Lo Hsing-han went underground and teamed up with the SSA, which agreed to shelter him – if he pledged to sell all his opium to the US government. Adrian Cowell, a British documentary filmmaker who spent 16 months with the SSA in 1972-73, helped the Shans draft a proposal to that effect to the US government. But just as Cowell was going to deliver it to the US embassy in Bangkok, Lo Hsing-han was arrested near the Shan border in northern Thailand – and extradited to Burma. He was sentenced to death, for ‘rebellion against the state’, a reference to his brief alliance with the SSA – but not for opium trafficking, which he had official permission to engage in.

But Lo was never executed. Instead, he was released during a 1980 amnesty and given two million kyats (a lot of money at that time) by the government to build a military camp southeast of Lashio. Called the Salween Village, it became the base for a new home guard unit, this time under the government’s new pyi thu sit (people’s militia) program, which had been launched after the disbandment of the old KKY. The new agreement was effectively the same as the former accord between the military and the local militias: fight the rebels and gain, in return, access to government-controlled roads and towns for smuggling.

The other prominent KKY commander, Khun Sa, was arrested in 1969 after a meeting with representatives of the Shan resistance. His men subsequently went underground and, on April 16, 1973 kidnapped two Russian doctors from the Soviet-built hospital in Taunggyi. In exchange for their freedom, Khun Sa was released from jail in Mandalay on September 7, 1974. He rejoined his men in February 1976 and moved to Ban Hin Taek in northern Thailand. The former Loi Maw KKY was renamed the Shan United Army (SUA), ostensibly a rebel army fighting for the Shan cause.

But his presence in Thailand became an embarrassment, and, in January 1982, Thai forces forced him and the SUA out of Ban Hin Teak. But they simply moved to the southwest and established a new headquarters at Homöng across the border from the town of Mae Hong Son in Thailand. To strengthen his credentials with the Thais, who are closely related to the Shans, he began to emphasize the supposedly Shan roots of his movement. The first step was to assassinate the SSA officers who had links with the Thai security establishment and replace them with his own. Already in early 1978, when he was still based on the Thai side of the border, the SSA’s two most competent military commanders, Sam Mong and Pan Aung, disappeared without a trace when they were on their way to meet the warlord at Ban Hin Taek. In May 1983, when Khun Sa was in the process of being established at Homöng, Hseng Harn, the SSA’s chief liaison officer with the Thais, was killed in his home in Chiang Mai. After that, a string of assassinations followed, and all the victims were SSA officers based in the border areas.

The next step was to merge the SUA with Moh Heng’s group, and a new entity called the Mong Tai Army (MTA) was formed. After the death of Moh Heng in July 1991, Khun Sa became the official leader of the MTA and its political wing, the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS). But, to the surprise of many, in January 1996, Khun Sa surrendered to the Myanmar military, disbanded his army, and moved to Yangon where he lived until his death on October 26, 2007. A faction of the MTA, led by a then junior officer called Yawd Serk, resurrected the old SURA and became head of the RCSS. Later, when his forces had grown into a formidable army, he named it the SSA as well. That has caused some confusion, and the media usually refer to Yawd Serk’s army as SSA-South while the original SSA is called SSA-North. But those names are not used by either of those armies.

The original SSA, meanwhile, has gone through some good as well as bad times. On August 16, 1971, a political wing called the Shan State Progress Party (SSPP) was formed, and the movement appeared stable. But that changed when their opium proposal was eventually considered by the US government – and rejected. The SSA had hoped to get at least some moral support from the West, but when that failed, they turned to the CPB, which then supplied them with guns obtained from China. The alliance with the CPB caused a split within the SSA, and old leaders like Chao Tzang Yawnghwe and his close companion Sao Hseng Suk (Khun Kya Nu) retired in Chiang Mai. Chao Tzang later moved to Canada where he became a well-respected academic. He died there on July 24, 2004. Khun Kya Nu passed away in Chiang Mai on August 13, 2007.

Today’s SSA/SSPP is closely allied with the CPB’s successor, the United Wa State Army (UWSA) and depends on it for military supplies. But, like the UWSA, it entered into a ceasefire agreement with the Myanmar military in 1989 and was then able to establish a headquarters at Wan Hai, a village in central Shan State. It has been under attack on several occasions, but, at least for now, the ceasefire seems to be holding. The RCSS, on its part, signed the military’s so-called ‘Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement’ (NCA) on October 15, 2015 and has since been preoccupied with real estate development in southern Shan State.

While the rest of the country is in turmoil, the Shan armies – whose combined strength could perhaps be as many as 20,000 troops – are staying in the background, not participating in the nationwide uprising against the junta that seized power in February 2021. There is heavy fighting in Shan State, but between the Myanmar military and Kachin, Palaung and Kokang forces in the north. Where that leaves the Shan armies in a nationwide context is hard to say, but the lack of activity on their part may cause bitterness and anger among the forces that are resisting the self-proclaimed State Administration Council (SAC) junta. The RCSS especially may even be seen as an ally of the junta. As recently as October 2023, Yawt Serk met SAC chairman Senior General Min Aung Hlaing in Naypyitaw where they, according to an official announcement, “cordially discussed the necessary measures for the peace and stability of Shan State and the nation.”

And, 60 years after the first attempt to unite the Shan forces under one command, they remain bitterly divided. There were even clashes between the RCSS/SSA and the SSPP/SSA when the former tried to take over areas in northern Shan State after it had signed the NCA – and that is definitely not what those who met in Chiang Mai in March 1964 had envisaged. But the rough and tumble of Shan politics is as old as the movement itself. And, today, there are no leaders like Chao Tzang Yawnghwe, who actually had a vision of what kind of political and federal system they should be fighting for.