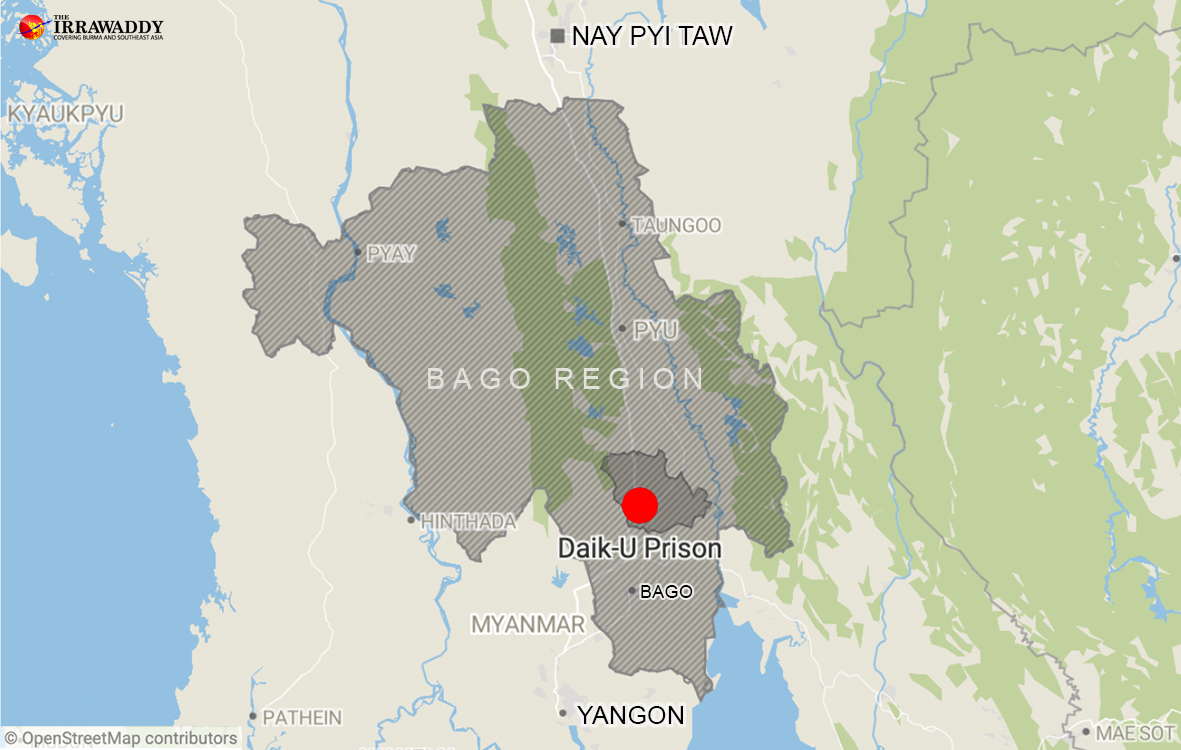

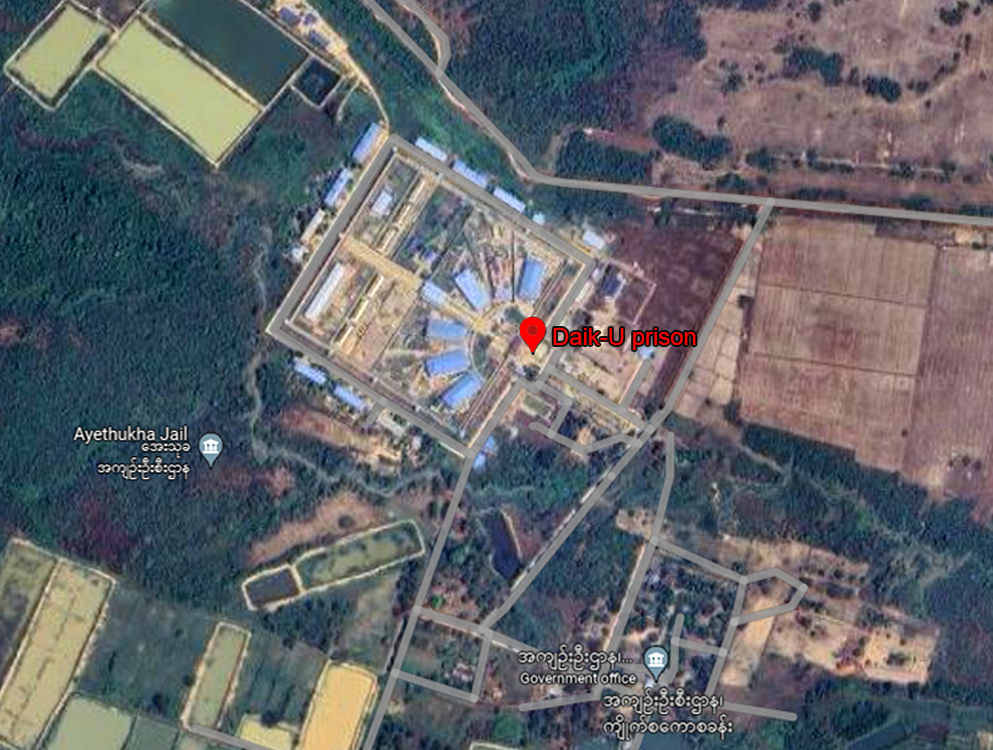

Between late May and early July last year, 37 prisoners, including more than a dozen political detainees, vanished after being pulled from their cells in Daik-U Prison in Bago Region near Yangon. It is the largest mass disappearance of prisoners held by the Myanmar junta since it seized power in a February 2021 coup.

The junta later announced that a group of detainees had been removed as part of a “prison transfer”, and informed some of the families that their loved ones had died en route while trying to escape, though the bodies have not been returned. The reasons given for their deaths have been widely dismissed as lies by family members, rights activists and analysts.

The Irrawaddy has conducted an investigation in an effort to shed light on the fate of these 37 individuals, examining death notices sent to the families by the Daik-U Prison authorities, and interviewing sources close to the victims, as well as family members and representatives of political prisoners’ rights groups.

How the ‘dark day’ began

“It was a dark day for my brothers,” says Ko Thiha, a former political prisoner at Daik-U, recalling the scene that unfolded in the early morning hours of May 25 in an interview with The Irrawaddy following his release in August.

On that day about 20 prison staff wielding sticks, shields and iron chains arrived at Ko Thiha’s cell block and began calling out inmates’ names off a list. Around a dozen were from his block—including one from his cell and others from neighboring cells—while the rest were from other blocks.

The prisoners on the list were taken for “interrogation” in connection with the activities of resistance forces and then moved to solitary confinement, he said. Not long after, over a dozen prison staff were themselves detained and jailed for allegedly helping political prisoners obtain mobile phones.

Ko Thiha also learned that some of the prisoners were being tortured. He was told this by another political prisoner who had encountered an inmate named Yar Lay (aka Ko Zin Myint Htun), a close friend of Ko Thiha. Yar Lay, who was among those who had been moved to solitary confinement from their cells on May 25, conveyed a message via the other political detainee, saying that he was fine, but the prisoner said he noticed signs of torture and beatings on Yar Lay.

In at least one case, the junta acknowledges that a prisoner died on the grounds of the prison. Ko Thant Zin Win, 19, one of the first political prisoners to be summoned, is believed to have been killed later during interrogation. The Prison Department claimed he died of heat stroke. He had worked as a recruitment officer for the People’s Defense Force (Bago)—or PDF Bago—and was sentenced to over 80 years in prison.

A week later, the authorities informed Ko Thant Zin Win’s wife of his death. She is herself serving a 10-year sentence in the same prison for supporting resistance forces, said a source close to her, who requested anonymity for fear of reprisals.

“His wife couldn’t believe the news and said she would only accept that he had died if she could see the body,” the source said. However, the prison authorities refused her request. She was simply given the handicrafts her husband had made out of instant coffee bags while in his cell.

The family was not allowed to retrieve the body or hold funeral rites in line with religious customs, which dictate that a ceremony should be held within a week of death in order to free the spirit from the body. Indeed, none of the families in this case who were told that a relative in the prison had died has been allowed to collect the body of their loved one.

PDF (Bago) later stated that Ko Thant Zin Win died after being tortured at the Pyin Pongyi interrogation center in Bago Township. The Irrawaddy has not been able to independently verify this.

Ko Thiha said the rest of the missing political prisoners were likely to have been taken to the same junta interrogation camp, citing information he got from a prisoner who was returned to Daik-U Prison after a week at an interrogation camp.

The prisoner did not know exactly where he had been taken, as he was blindfolded, but said they were all taken out of the prison and interrogated at the same place.

Ko Thiha said that on June 7, he saw three of his friends, who were on the list and had been moved to solitary confinement, being taken to another place in a prison truck. He couldn’t see whether there were any others inside the truck, however.

A week after Yar Lay was taken from his cell, Ko Thiha learned that he was no longer at Daik-U, when prison authorities rejected a food parcel sent by his wife, saying Yar Lay was no longer there.

During this period, Ko Thiha and other inmates were subjected to unusually tough security measures in the prison. Prisoners were locked in their cells for days, and he noticed that prison staff were being replaced by soldiers. “Security was very tight; [we were] guarded by military personnel in the prison compound.”

By June 27, political prisoners learned that in total 37 prisoners, including political detainees, had been removed from the prison. Many of them are likely to have been gone for at least a month by this point, said Ko Thiha, who had personally witnessed the three being put into a truck on June 7 and had learned about Yar Lay’s removal.

‘Warning shots’ kill 10 shackled prisoners

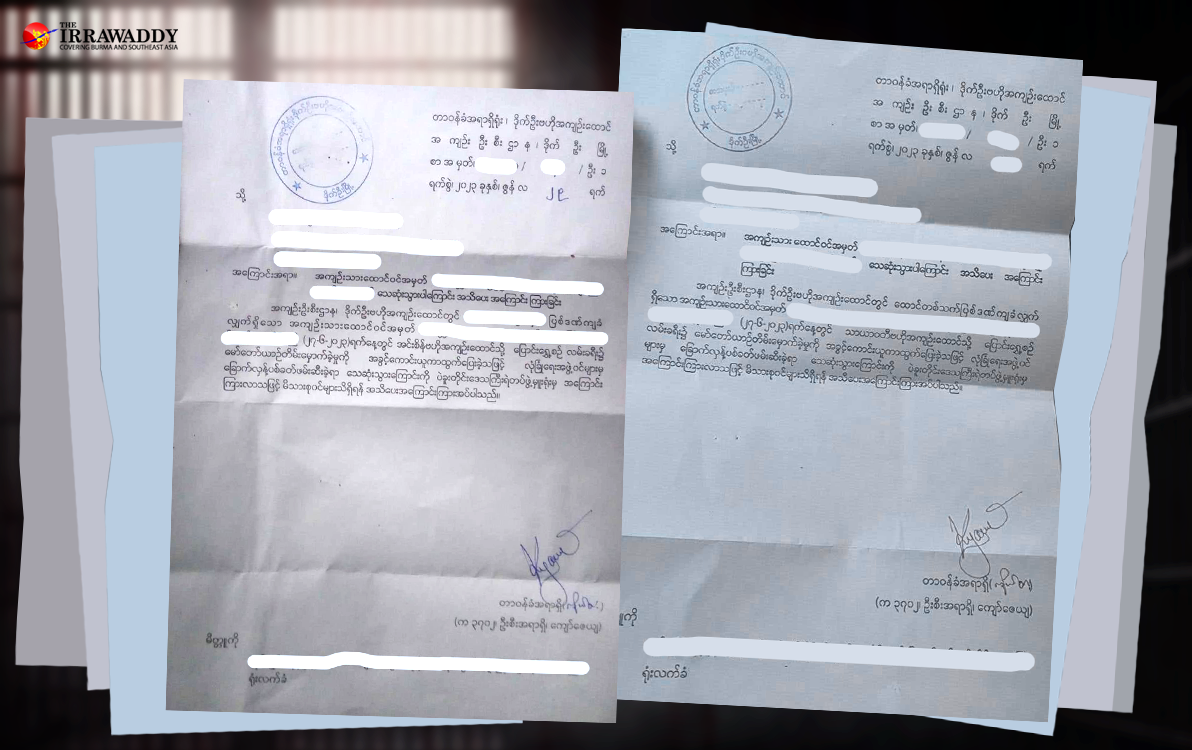

Starting from July 7, prison authorities sent death notices to the families of at least eight of the 37 prisoners. The notices included the prisoner’s identification number and the seal of Daik-U Prison, and were signed by a staff officer of the prison, Kyaw Zeya.

The letters, seen by The Irrawaddy, state that the prisoners were killed by “warning shots” fired by security personnel while the inmates were being transferred from Daik-U to two different locations: Yangon’s Insein Prison and Thayawaddy Prison in Bago Region.

Yar Lay’s wife received a notice of her husband’s death on July 7. She was informed that his death occurred while he was being transferred to Insein Prison on June 27. The letter stated that he took advantage of a vehicle accident and tried to run away. Thus, it said, a security officer fired “warning shots” as part of efforts to recapture him, and he was shot and killed.

The families of at least two others were informed by local authorities that their loved ones had died in the same way.

At least three of those killed were family members of female political prisoners incarcerated at Daik-U Prison at the time, said a source with direct knowledge of the women’s wards in Daik-U, and who requested anonymity for security reasons.

One lost her husband, one lost her father and one lost an uncle, the source said. The one who lost her father was not informed about his death until three months later, she added. The woman received the information after authorities rejected her request to meet her father. Intra-prison visits are normally allowed for family members jailed in the same prison.

“She cried for days, murmuring that ‘My Ah Pa has gone,’” the source added.

Some odd facts

Among the first families to receive a letter was that of Ko Khant Lin Naing, the vice chair of Bago District All Burma Federation of Student Unions. The 20-year-old student activist was arrested in December 2021 and sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment on terrorism charges.

Although the letters were dated June 29, none was delivered before July 7. The letters received by the families of prisoners all had the same wording; none of these families has been allowed to retrieve the bodies of their loved ones.

Not being able to see the bodies has only created more uncertainty, arousing suspicion among prisoners’ rights monitoring groups and former political prisoners that the victims were killed during the interrogation process.

The reasons for the deaths given in the notices are highly implausible, with prisoners traveling to two different locations somehow all being killed by warning shots after trying to escape following vehicle accidents.

Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) spokesperson Ko Aung Myo Kyaw said if it actually happened the way they claimed, there would be no way to cover up such accidents or shootings outside the prison.

“It is impossible that it would not be reported or noticed by residents nearby, and the prison would have informed them [the families] immediately,” the spokesman said. “But they concealed it and only informed [the families] after a long time. It is totally dishonest,” he added.

Not only was their right to hold a funeral denied, but the families were also verbally warned not to share information about the letters with others, according to sources close to them.

Former political prisoners and prison rights activists interviewed by The Irrawaddy said it is standard practice for prisoners to be shackled by chains at the wrists and ankles when being transferred, to prevent them from running away. In most cases two inmates are shackled together, they said.

Ko Thiha pointed this out and asked, “How could it be possible to run with chains?”

He also recalled conversations with some of his friends who were among the victims, in which it was agreed that they would never leave a cell even if the door was left open. “We wouldn’t let them [the junta] add more charges for attempting to escape,” he said, while recalling their shared belief that the revolution will win in the end.

Two of the death notices from the Prison Department seen by The Irrawaddy are numbered “001” and “014”, raising the possibility that as many as 14 prisoners were killed in the case.

According to Ko Thaik Tun Oo, a founder of the Political Prisoners Network-Myanmar (PPN-M), which was formed last year by former political prisoners, no other Daik-U Prison inmate deaths have been reported for the period in question.

Junta retaliation: ‘Political detainees are their enemies’

Many rights activists and former political prisoners believe political prisoners are killed in retaliation for the anti-junta activism they engaged in prior to their arrest.

Prisoners’ rights activists told The Irrawaddy that based on their experiences, the more losses and attacks junta forces suffer outside, the more persecution political detainees experience inside prisons.

“They [prison staff] think political detainees are their enemies,” said Ko Thaik Tun Oo, adding that many prison staff are former military personnel.

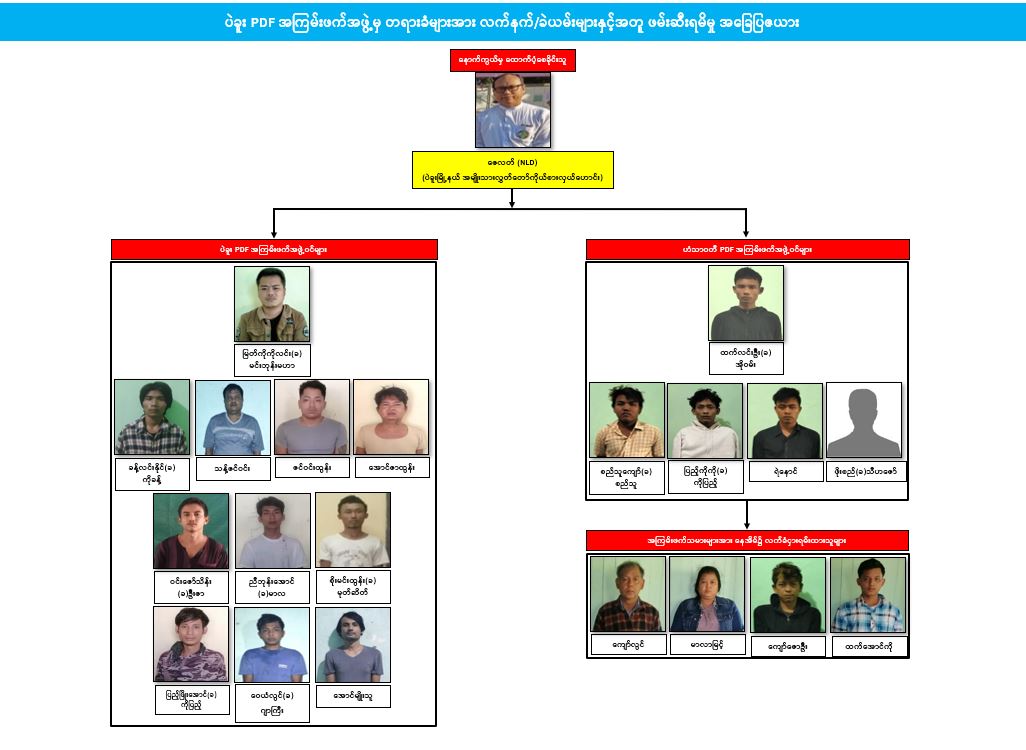

According to the junta’s announcement on Dec. 21, at least five of the killed or missing political prisoners from Daik-U Prison, including Ko Khant Lin Naing, were arrested in connection with the activities of PDF Bago and for alleged involvement in guerrilla attacks on junta targets.

Ko Phyo Maung, a spokesperson for PDF Bago, said the group learned that five of its resistance fighters were killed in the Daik-U Prison event.

“They had all been handed lengthy prison sentences. But the junta intentionally interrogated them again and killed them,” Ko Phyo Maung said, while also vowing to continue the fight until the military dictatorship is toppled.

U Tun Kyi of the Former Political Prisoners Society (FPPS) said the junta intentionally selected PDF members and those against whom they have grudges for their anti-junta activism, or who dared to defy the unjust restrictions of the prison, under the pretext of “transferring” them, and then killed them, offering the excuse that they had “attempted to escape”.

PPN-M reported at least 35 deaths of political prisoners in prisons across the country last year, with 18 dying due to torture and extrajudicial killings, and 17 others due to lack of adequate medical care.

“2023 also saw the largest number of political prisoners being killed [ever],” Ko Thaik Tun Oo said.

According to the AAPP, since the coup, around 80 political prisoners have died in prisons due to harsh conditions, insufficient medical assistance and torture.

Since July, the junta has banned delivery of foreign medicines, leaving prisoners with chronic conditions like diabetes, high blood pressure and heart and stomach problems to fend for themselves—sometimes with fatal consequences.

Prison authorities only provide paracetamol and the allergy relief medication Burmeton (chlorphenamine), whatever the nature of a prisoner’s illness, former political prisoners and rights groups said.

In September last year the regime even barred detained democracy leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, 78, who was suffering from a serious gum disease, from seeking proper medical treatment. They have rejected her requests to consult an outside physician at qualified facilities outside the prison system.

The Irrawaddy was unable to reach the junta-run Myanmar National Human Rights Commission (MNHRC), the sole organization with access to prisons and detention facilities across the country, and which has a mandate to inspect prisons and carry out “human rights promotion and protection”.

The Irrawaddy asked the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Myanmar for comment on the case, and what action it had taken in relation to it. A local media officer for the ICRC said they were not able to answer every question in detail “as the organization’s preferred way of working, in all countries, is bilateral and confidential engagement with the relevant actors to allow for open and honest discussions.”

In cases where contact has been lost with loved ones, family members can reach out to the ICRC and it will provide feedback only to them, the local media officer added.

‘Attempt to escape’: a familiar claim

The “killed while attempting to escape” claim is not new, pointed out prisoners’ rights groups. The same pretext has been used in the deaths of other political detainees, including five additional cases last year—two in Mandalay Region’s Myingyan Prison, one in Thayawaddy and two in Insein.

In Insein Prison, the alleged killers of pro-junta propagandist Lily Naing Kyaw—Kaung Zarni Hein, 23, and Kyaw Thura, 30—were supposedly shot dead as they attempted to escape while being taken to North Dagon Township in Yangon, the junta said at a press briefing on July 6 last year.

Shortly after Kaung Zarni Hein’s arrest in early June, his mother and sister were shot dead at their home in Yangon’s Htantapin Township, in an apparent revenge killing by pro-military actors.

AAPP spokesperson Ko Aung Myo Kyaw condemned all of these prisoners’ deaths, saying they amounted to the worst spate of extrajudicial killings in the country’s history.

“Now they are taking out prisoners, interrogating them again, and killing them as they wish,” he said.

The junta’s spokesperson for Bago Region, U Tin Oo, denied that any prisoners at Daik-U had disappeared or been killed.

“Who told you about that?” he asked upon being questioned about the incidents, adding, “It is not true. No prisoner has gone missing and nothing happened. Everything is normal there [at Daik-U Prison],” before abruptly hanging up.

Ray of hope

Some information that recently emerged from Insein Prison has raised hopes among family members that at least some of the 37 reached their destinations after being removed from Daik-U.

According to Ko Thaik Tun Oo, around 20 bloodied and injured detainees arrived at Insein Prison in the last week of May 2023. Given the timing and the fact that no other prison transfers have been reported as occurring at that time, they may have been prisoners from Daik-U, he said.

The Irrawaddy has not been able to independently verify the arrival of the prisoners, however.

Relatives of the missing prisoners have visited Insein and Thayawaddy prisons but received no information from the prison authorities.

Bo Tauk of the Eastern Bago Former Political Prisoners Group said family members are living in anxiety, worry and daily fear. He said that so far the group had not received any information about the missing prisoners or those who reportedly arrived at Insein Prison.

None of the families of the killed political prisoners would comment on the killings or disappearances of their loved ones to The Irrawaddy, fearing reprisals for speaking to the media. However, two family members of missing prisoners provided the depressing information that they still hadn’t received any news.

The source close to a family member of one of the disappeared prisoners said killing political prisoners who were already being persecuted through incarceration was the “worst case of inhumanity”.

Who is accountable?

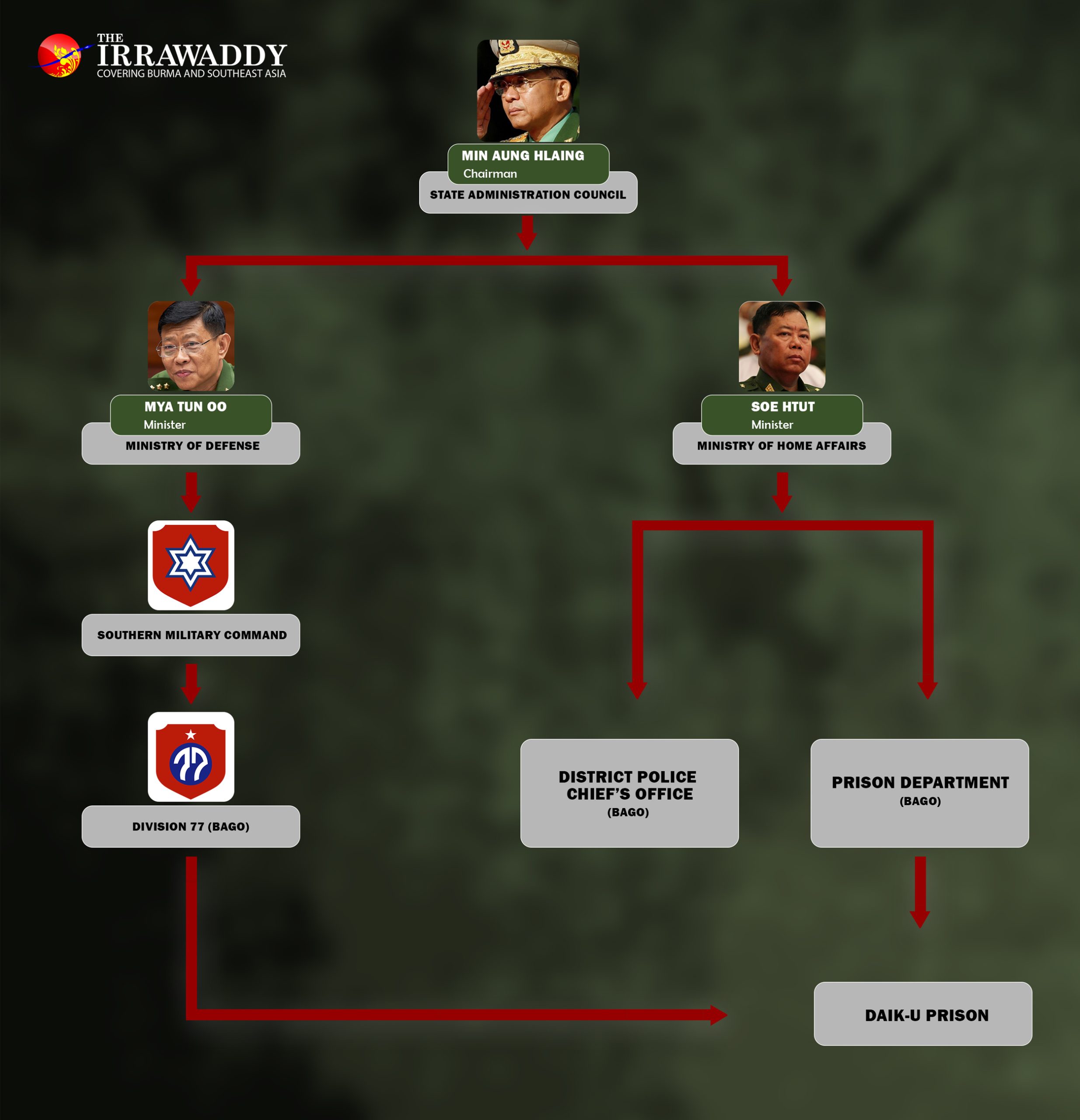

While it is not yet clear exactly who issued the orders in this case, or who expedited the killings and disappearances, we can identify certain people who should be held accountable. Furthermore, interviews with sources and documents obtained by The Irrawaddy show that junta military personnel and staff of the Home Affairs Ministry, which has authority over Prison Department staff, were involved in the case.

First and foremost, as the head of the regime’s State Administration Council (SAC), which has full control over the military and the Home Affairs Ministry, junta boss Min Aung Hlaing is ultimately responsible for the killings and disappearances of political prisoners at Daik-U Prison.

Furthermore, political prisoners’ rights advocates and sources believe junta soldiers from Bago-based Myanmar military Division 77 and members of the Office of the Chief of Military Security Affairs (OCMSA, or Sa Ya Pha)—a military intelligence unit—in Bago were involved in the case, as detainees were reportedly taken to a military interrogation center.

Ko Aung Myo Kyaw of the AAPP said the junta’s then-Home Affairs Minister Lieutenant General Soe Htut, who ran the ministry and was responsible for the Prison Department and the Bureau of Special Investigation, also bears the highest level of accountability in the case as without his permission, the killings and disappearances could not have been carried out.

Additionally, the junta officials who gave orders at various levels and those who personally carried them out should all be held responsible for their actions, he said.

“The SAC [as the junta’s governing body] is also responsible for the extrajudicial killings of political prisoners, as they allow it,” he added.

Under the 2008 Constitution, the Ministry of Home Affairs operates under the military’s direct control. The then home affairs minister, Lt-Gen Soe Htut, was a member of the SAC and a close associate of its chair, regime chief Min Aung Hlaing.

Ko Thaik Tun Oo of PPN-Myanmar meanwhile named the then prison officials San Aung, Thaik Htwe and Myo Thiha Aung as among those responsible for the case. The Irrawaddy couldn’t independently verify their involvement.

He added that the District Police Chief’s Office in Bago also bears major responsibility. In the death notices sent to prisoners’ families, it is stated that the District Police Chief’s Office in Bago reported the alleged vehicle accidents, and deaths of prisoners due to warning shots, during the “prison transfers”.

“It is sad that no one from the Prison Department has yet been put on the sanctions list despite the fact that torture and killings of political detainees are widespread behind bars,” he said.

Given the information gleaned from the interviews and documents obtained, the likely chain of command behind the killings and disappearances of 37 prisoners in Daik-U Prison could be described as follows:

U Tun Kyi of the FPPS also described the Daik-U case as the worst and most serious human rights violation in a prison his group had encountered.

“The junta will continue to commit similar acts as long as they are immune from punishment and the international community is silent. It is like issuing a butcher’s license to them,” he said.

The AAPP’s Ko Aung Myo Kyaw and Ko Thaik Tun Oo of PPN-M also stressed the importance of ending the junta’s impunity in order to prevent them from blatantly violating not only domestic laws but also international laws by killing political detainees.

“We must end their [the military’s] impunity for their atrocities and find justice for our fallen comrades. For now, all detainees of the junta have no right to life and are at risk of extrajudicial killing.”