This article is published by The Irrawaddy’s Investigative Desk.

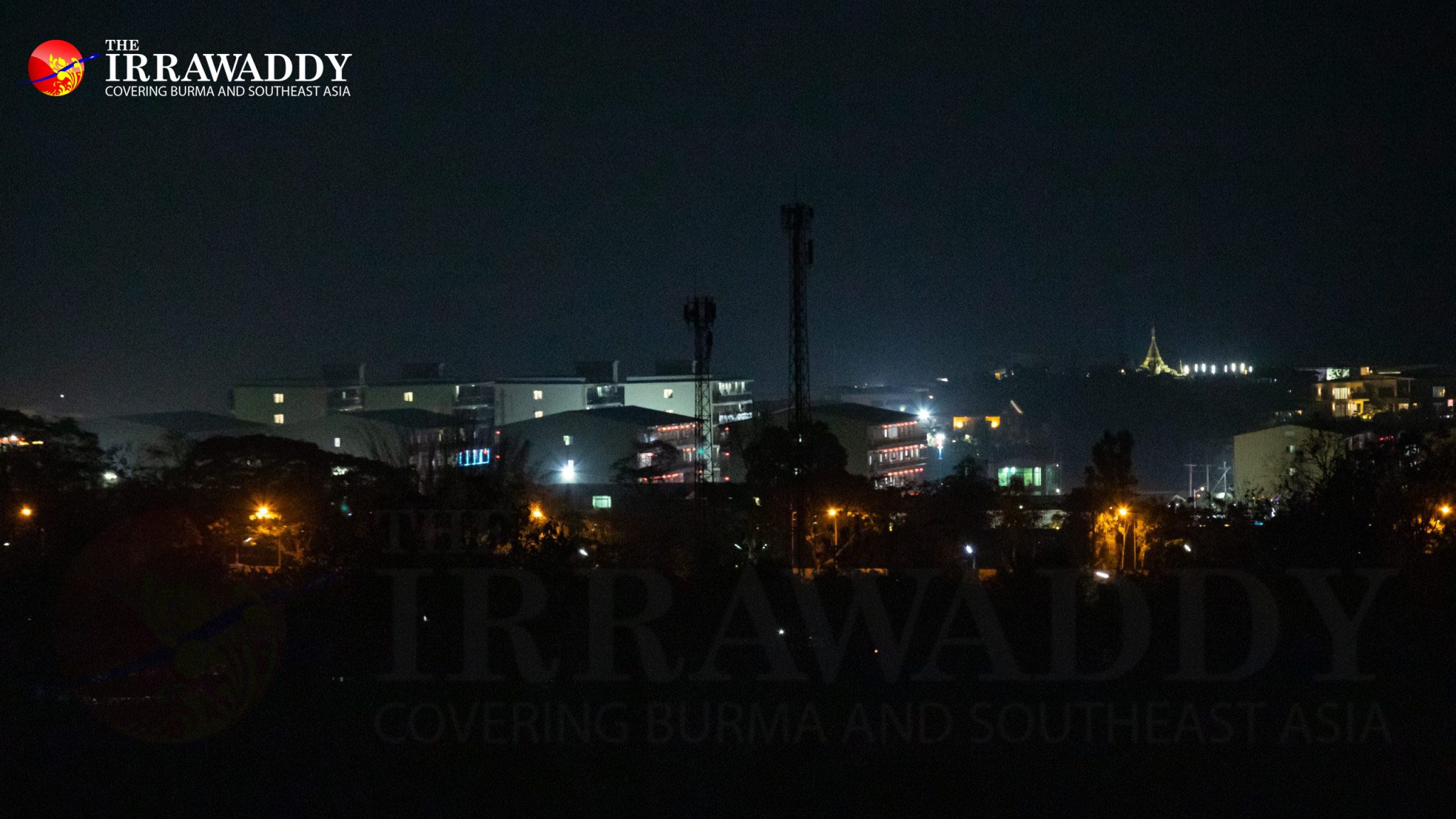

“It is a town impervious to bullets and bombs. No matter how fierce the fighting gets near the town, not a single bullet lands here,” Saw Htoo Htoo explained while taking pictures of buildings at the brightly illuminated KK Park.

Lights from the hotels, casinos and many other structures that have sprung up at KK Park, a Chinese-invested so-called “new city” project in Karen State’s Myawaddy Township on the Thai-Myanmar border, illuminated the sky so brightly that the lights from Mae Ku Village across the Moei River in Thailand seemed as faint as distant fireflies.

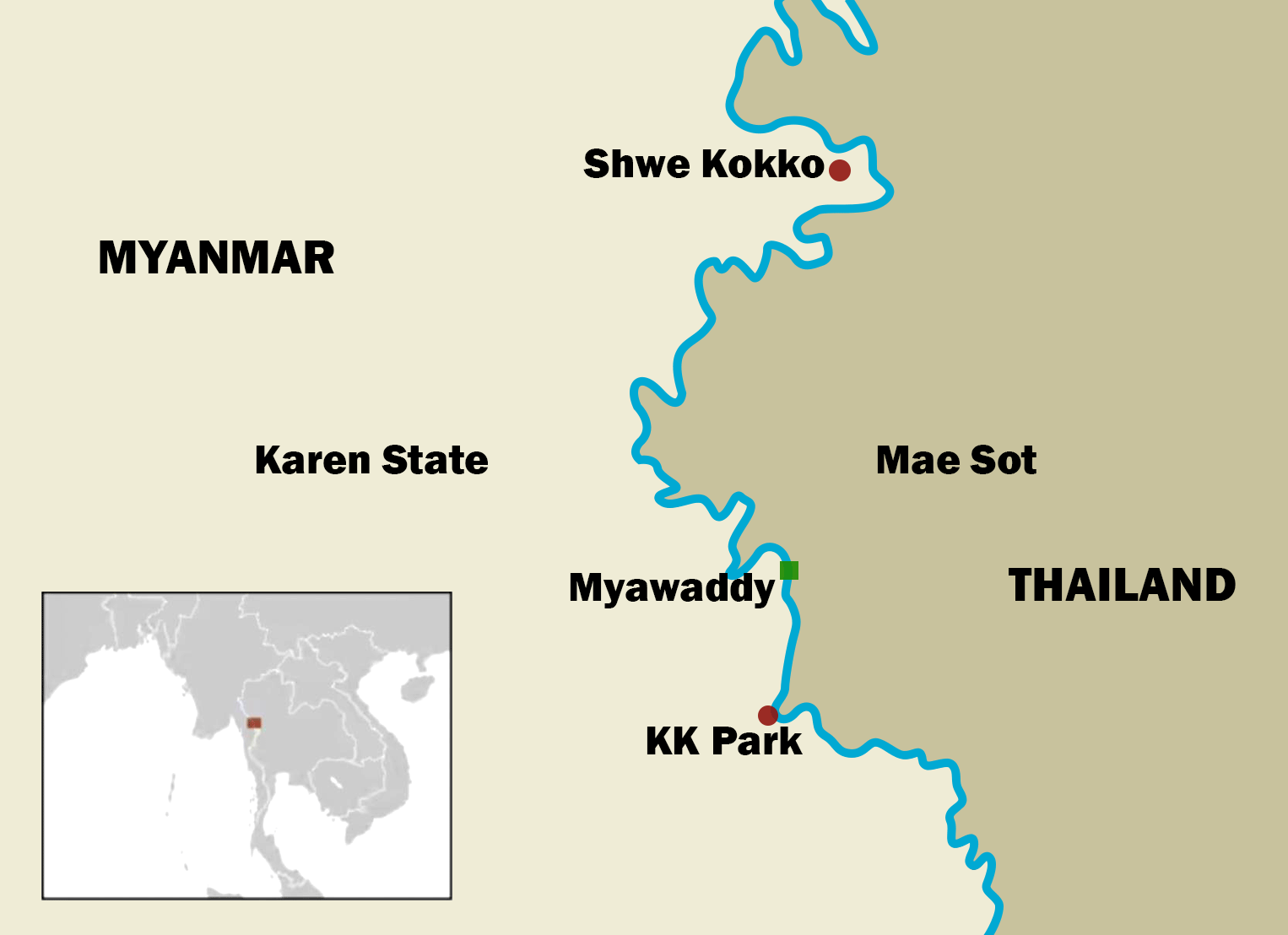

KK Park is located in the south of the township, near the village of Maw Hto Talay, just across the river from Mae Ku in Mae Sot town in Thailand’s Tak District.

“Those vehicles carry Chinese citizens across the Moei River to work at KK Park. They live in Thailand and work on the Myanmar side of the border,” said Saw Htoo Htoo, gesturing at a passing fleet of vehicles. Saw Htoo Htoo has had contact with Karen ethnic armed organizations based on the Thai-Myanmar border for several decades and is quite familiar with KK Park’s development.

Repeatedly expressing his surprise at the speed with which KK Park’s cluster of high-rise buildings emerged in the once rural area over the past three years, Saw Htoo Htoo added: “Senior officers from the Karen National Union [KNU] are involved in this project.”

A ‘new city’ oddly unscathed by war

KK Park is located in an area where the KNU and Brigade 6 of its armed wing, the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), are active. Junta troops; the Border Guard Force (BGF); the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA); the Karen National Liberation Army-Peace Council (KNLA-PC); and the People’s Defense Forces (PDFs)—which emerged after the 2021 coup—are also active in the area.

In December 2021, within a year of the military coup, fighting broke out in Myawaddy Township, with allied forces led by the KNLA pitted against junta troops and the BGF. (The BGF has since ended its alliance with the junta.)

To the west of KK Park lies Lay Kay Kaw town. With the support of Japan’s Nippon Foundation, the town was built from scratch in 2015 as a “town of peace” in recognition of peace negotiations between then Karen State Chief Minister Zaw Min and then KNU chairman Saw Mutu Say Poe.

However, the fighting has spread to Lay Kay Kaw and neighboring areas including Maw Hto Talay, Falu, Wawlay Myaing and elsewhere.

Lay Kay Kaw and surrounding villages have been badly damaged by junta air and artillery strikes during the fighting, with many residents forced to flee across the border to Mae Sot. Junta shells have also hit villages in Thailand, prompting the Thai army to tighten border security.

However, not a single bullet has ever struck KK Park: hence Saw Htoo Htoo’s observation that it is “impervious to bullets and bombs”.

Inside KK Park

KK Park houses casinos, hotels, restaurants, nightclubs, brothels and online scam centers, according to those working there and some who have escaped.

The online scam centers operate various types of criminal enterprises including “romance scams” and fraudulent investment schemes, and are notorious for human trafficking and forced labor.

The project is controlled by Chinese citizens who operate the prison-like scam centers, said Naw El Kalu Phaw, who worked at a casino in KK Park for eight months.

“You are not allowed to leave the building where you work. At lunchtime, Chinese people and people from other countries would come to eat lunch [at the building where she worked]. I didn’t know which buildings they worked in,” she said.

The 30-year-old was forced to work 12 hours a day as a dealer. Made miserable by the long working hours and the suffocating, prison-like conditions, she eventually resigned on health grounds.

“Working there felt like being in a prison, except that I didn’t have to work under the sun,” she said.

Ko Thiha, who at the time he spoke to The Irrawaddy was working at one of KK Park’s scam centers, said he was forced to work for romance scams targeting gay men from Asia and Europe. Sometimes he also had to masquerade as a woman, using profiles with women’s pictures, to lure victims.

He himself was lured by the false promise of high-paying work after responding to a job offer seeking candidates who were computer literate and could speak English. Amid a lack of jobs and money-earning opportunities in Myanmar, the advertised monthly salary of 1.5 million kyats (about US$713 at current official rates) was enticing, and he rushed to apply for the job without considering that it could be a scam operation, Ko Thiha said.

“At first, I thought they were recruiting translators. It was only after I arrived here that I found I had to do a completely different job. I had to expose my body parts later during sex chats. [I realized] this is not OK anymore. But you know what [harsh punishment] would happen to me if I refuse. So, I will have to complete the three-year contract,” said the married man, who has a daughter.

“I have a guilty conscience about raising my daughter with money earned from doing a job like this. What’s more, it’s illegal,” he added.

He said victims of trafficking are punished if they do not meet the demands of their captors. Some who attempted to run away were tortured after being recaptured, and some Chinese citizens even attempted suicide by jumping from buildings, Ko Thiha said.

One crime syndicate at KK Park runs an investment scam that lures people from any countries it can reach—including Myanmar and Thailand—into buying nonexistent shares with the promise of an attractive return, said Ma Wutt Yi, who currently works for the operation.

Ethnic Chinese people from Myanmar, as well as people from China, Thailand, Laos, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and India work in the same department, where they are forced to defraud victims from their home countries, she said.

Every scammer is provided with a computer and handphone installed with apps, software and social media accounts, all controlled by a central computer. Scammers use the social media accounts to prey on the victims.

Ma Wutt Yi said: “For instance, I target Myanmar migrants in Thailand and Myanmar citizens in Myanmar. I invite them to buy shares by telling them that they can a make a certain percentage in two weeks on a 10,000 baht [about $277] investment. Initially, regular returns are paid out to them to develop trust. After they invest more, we seize their money and close the account.”

Scammers are overseen by supervisors, and those who fail to meet their targets are subjected to various kinds of torture including solitary confinement. The scam operators keep the trafficking victims’ identity cards.

Ma Wutt Yi said: “We don’t want to defraud our fellow Myanmar citizens at this difficult period for our country. We can’t escape. They keep our identity documents, and we have to complete the contract. I am too ashamed to tell my friends that I am doing such a job.”

Those who have worked as scammers usually keep it a secret because such work is illegal and they fear reprisals from the scam syndicates, she said.

Foreign victims

Within two years of the launch of operations at KK Park, it became notorious for human trafficking, online fraud, forced labor, systematic torture and organ trafficking targeting people from regional countries.

A story published in July 2023 by the US-based Pulitzer Center reported on human trafficking, torture, killing and organ trading at KK Park, citing the accounts of escapees.

Around the end of 2022, the Thai Embassy in Yangon asked the Myanmar regime to help rescue a Thai citizen who had been abducted and forced to work at an online casino at KK Park. Documents sent by the junta’s Immigration Department to the KNU’s liaison office about the Thai government’s request were seen by The Irrawaddy.

On Dec. 22, six Malaysian citizens who were forced to work as scammers at KK Park and subjected to torture were rescued, according to Singapore’s The Straits Times. The escapees said those who fail to meet the demands of their captors were subjected to various kinds of punishment such as simulated drowning, beatings, starvation and confinement.

The Times of India reported in September 2022 that some 300 Indian citizens had been forced to work for cybercrime syndicates at KK Park. Of them, nine IT technicians from Kerala State were released after paying large sums of money to the syndicates.

KK Park’s origins

The KNU leadership is widely believed to be involved in KK Park, which was developed by China’s Huanya International Holding Group. Padoh Saw Roger Khin, the head of the KNU’s Defense Department and a member of the organization’s Central Executive Committee, personally attended the groundbreaking ceremony of KK Park on Feb. 10, 2020.

According to the KNU, Padoh Saw Roger Khin was merely representing a group of landlords when Hong Kong-based Trans-Asia International Group, a subsidiary of Huanya International Holding Group, signed a land-lease agreement with Myanmar’s Mulaei Alin Co. The latter company exited the project in 2022 and another company from Myanmar, Trust Star Co. Ltd., filled the vacancy around the end of 2022, the KNU said.

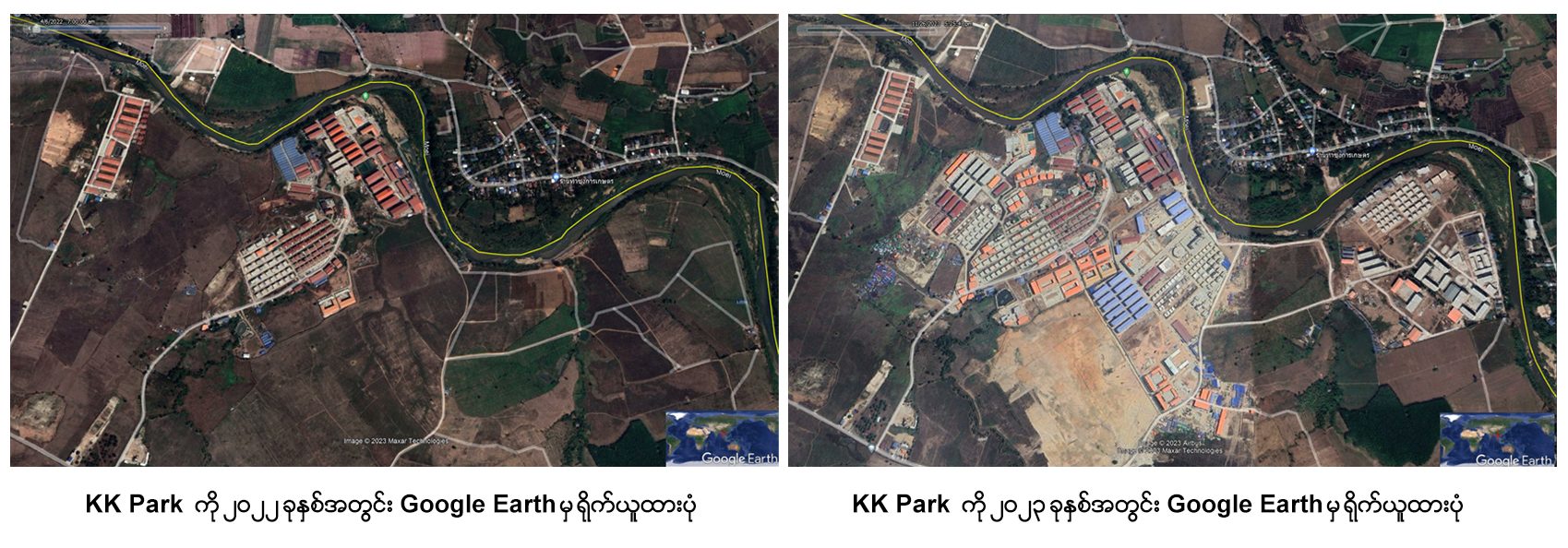

According to Google Earth satellite images, the site on which KK Park now stands was farmland until February 2020. Construction began in March of that year, and many buildings emerged around the end of 2022.

Construction materials for the KK Park project are imported across the Moei River from Thailand. An exclusive jetty—clearly visible in the satellite photos—was built in the south of Mae Ku Village. According to those who have worked at KK Park, online casinos and scams have been operating there since 2021. More buildings are currently under construction at the sprawling site.