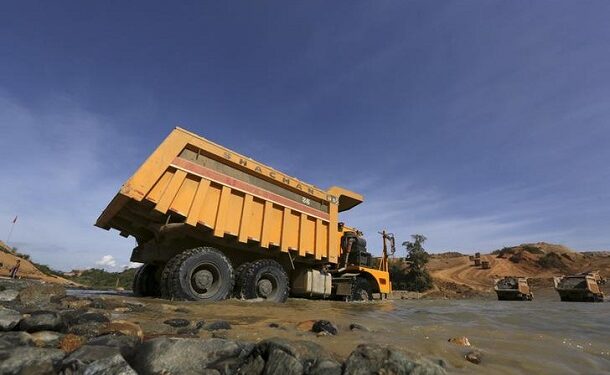

Myanmar’s government currently collects much of the trillions of kyat generated by oil, gas, gemstones and other minerals each year, primarily through its state-owned economic enterprises (SEEs). In the face of such centralized control over revenue, many ethnic groups have long asserted their right to make decisions over resource management in their states. In fact, combatants in areas of active conflict and leaders from several ethnic minority parties—particularly those associated with Kachin, Rakhine and Shan states—have openly called for greater resource revenue sharing.

These appeals are only expected to get louder as the NLD forms a new government. In its election manifesto, the party promised to “work to ensure a fair distribution across the country of the profits from natural resource extraction, in accordance with the principles of a federal union.” This statement implies at least two things: First, that the party intends to transform Myanmar into a federation, where states and regions have true sovereignty over some government responsibilities; and second, that it intends to enact a natural resource revenue sharing system.

A resource revenue sharing system will undoubtedly be on the table during evolving discussions on federalism. However, as we have seen in other countries, these systems come with considerable risks. In the most extreme cases, such as Peru, they can actually exacerbate conflict, encouraging local leaders to use violence to compel greater transfers from the central government or gain control over mine sites. While these experiences are atypical, natural resource revenue sharing often leads to financial waste, local inflation, boom-bust cycles and poor public investment decisions.

Myanmar is particularly susceptible to these risks as overall resource revenues officially recorded in the budget remain small—due to smuggling, underreporting, weak tax collection, and revenue retention by SEEs, among other causes. This means that there are limits to how much revenue sharing can help affected communities without the government first putting effort into capturing a bigger share of profits for the state.

How much money is at stake today? According to conservative estimates from Myanmar’s first Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) report, the government collected nearly 2.6 trillion kyat in oil and gas tax and non-tax revenue and another 442 billion kyat in mining revenues in fiscal year 2013/14. Together, oil, gas and mineral revenues made up 47.5 percent of government revenues (excluding the significant sums that SEEs retain for themselves) in the same year.

However, official revenue figures vastly underestimate the true size of the non-renewable resource sector. EITI figures only cover a portion of jade sales. And illegal mining and smuggling of minerals, especially jade, has been well documented. Some independent estimates put the true size of the mineral sector at more than 10 times official figures.

Currently, the 42 percent of resource revenues that are not retained by SEEs in their own so-called “Other Accounts” are pooled with other fiscal revenues in the Union budget. Some are then distributed directly to state and regional governments, which are responsible for financing local infrastructure, agriculture and some cultural institutions.

As part of the government’s effort to decentralize fiscal responsibilities, the amount of the overall budget allocated to all states and regions has increased in recent years, from 3.4 percent in 2013/14 to 7.6 percent in 2014/15 to 8.7 percent in 2015/16. The government now says that it is using population, poverty and regional GDP indicators to determine how much it gives each state or region from this pool of money.

Research from the Natural Resource Governance Institute’s (NRGI) new report “Sharing the Wealth: A Roadmap for Distributing Myanmar’s Natural Resource Revenues,” generally corroborates this claim, but with qualifications. Our research indicates that, in practice, the Union sends more money per capita to regions and states that have greater development needs, are conflict-affected, and whose politicians are more assertive. This year, for instance, Chin, Kayah, Tanintharyi and Kachin received the highest per capita allocations, while Ayeyarwady, Bago, Mandalay, and Yangon received the lowest.

But just because more money is going to states and regions does not mean that there is more accountability or that social services and infrastructure are improved relative to other parts of the country. Nor does this fiscal decentralization address local demands for greater autonomy over natural resource revenues.

Most state and regional officials still report to Union authorities in Naypyitaw. Furthermore, state and regional governments still have low capacity to develop and implement budgets effectively. This means that state and regional spending is not necessarily efficient or linked to a coherent economic development plan.

While true federalism—partial sovereignty for states and regions—would require constitutional reform, there are three steps the new government can take now to “ensure a fair distribution across the country of the profits from natural resource extraction.”

First, the government can start building national consensus on a natural resource revenue sharing formula. This way, all parties would have clarity on the issues and feel a sense of ownership over natural resource governance. This is the principle means through which resource revenue sharing can help stop violent conflicts. Indonesia spent nearly two years negotiating a resource revenue sharing deal with conflict-affected Aceh before coming to an agreement. The ongoing Union Peace Dialogue could be one forum for discussion of how a revenue sharing system could be administered. This discussion would not be a substitute for formal parliamentary and public discussions, but could support government efforts to build peace.

Second, the government could further decentralize by making state and regional politicians and officials accountable to local residents. It could also delegate resource management and expenditure responsibilities to these officials slowly, so they have time to learn how to perform these new roles. This can be done even without constitutional change. The Colombian and South African experiences offer some lessons for how decentralization can be achieved in unitary states (though neither case is an unmitigated success).

Third, the government could improve the transparency and oversight of natural resource revenues by cracking down on smuggling and illegal mining and publishing project-level information on all extractive projects. Without this information, state and regional governments cannot verify the value of minerals being extracted on their land and therefore cannot trust that they would receive their due under any revenue sharing formula. Myanmar could look to Bolivia and Mongolia, which lead the way when it comes to extractive sector transparency. For instance, the Bolivian government publishes, in a clear and understandable format, online data on transfers to and between subnational authorities and on hydrocarbon production by province, field and company.

Natural resource revenue sharing can be a key component of peace-building and decentralization in Myanmar. Mineral-rich Kachin, Mandalay, Sagaing and Shan, and onshore oil-rich Magway and Bago would undoubtedly benefit. Governments in other states and regions with pipelines that transport offshore gas may also profit. But unless done properly, resource revenue sharing can help perpetuate conflicts that have gone on for far too long.

Andrew Bauer is a senior economic analyst at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).