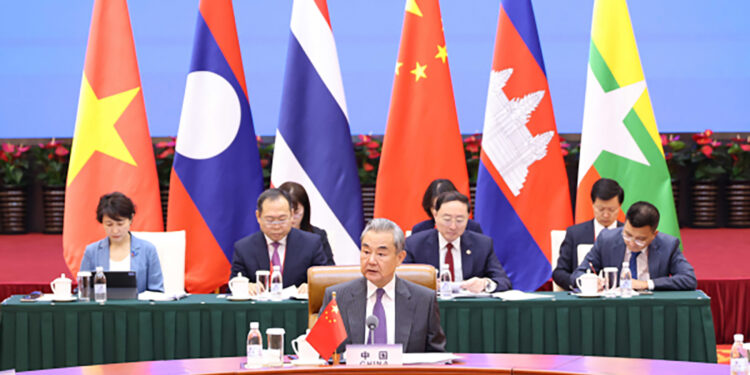

The Lancang-Mekong Cooperation initiative (LMC), established in 2016 under China’s leadership, presents itself as a beacon of regional cooperation and sustainable development. Yet beneath this veneer of multilateral harmony lies a sophisticated instrument of Chinese hydro-hegemony that has transformed the Mekong River into a tool of geopolitical leverage and a cautionary tale of how Beijing weaponizes water resources under the guise of cooperative frameworks.

China’s official narrative portrays the LMC as responding to regional needs for development and cooperation. However, examination of Chinese sources reveals a more calculated agenda. According to Lu Guangsheng from the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, the LMC represents China’s transition “from passive participant to active creator” of international mechanisms aimed at “stabilizing and coordinating China’s relations with Mekong countries.” This frank acknowledgment exposes the LMC’s primary function: securing China’s strategic interests through institutionalized influence.

The LMC’s creation coincides suspiciously with mounting criticism of China’s unilateral dam construction on the Lancang River. By 2010, downstream countries had begun protesting the severe impacts of Chinese dams, which caused unprecedentedly low water levels during the dry season while Chinese reservoirs remained full. The LMC emerged as China’s response—not to address these legitimate concerns, but to create a framework that legitimizes Chinese control over the river system.

Hydro-hegemony

China’s upstream dominance gives it overwhelming leverage over downstream nations. With eleven operational dams on the Lancang and plans for more, Beijing can manipulate river flows at will. During the 2019-2020 drought, China’s dam operations exacerbated water shortages downstream while Beijing selectively released water to demonstrate its “goodwill”. This pattern of creating crises and then offering solutions exemplifies what scholars term “hydro-diplomacy.”

Chinese academic sources are remarkably candid about this strategy. The Shanghai-based researcher admits that the LMC enables China to supply “policy support” and “public goods” to the region, positioning Beijing as the indispensable provider of water security. The mechanism allows China to present itself as a beneficent upstream neighbor while maintaining ultimate control over a resource vital to 70 million people downstream.

The LMC’s institutional design reinforces this asymmetry. Unlike genuine multilateral mechanisms, the LMC operates through bilateral arrangements between China and individual downstream countries, preventing unified responses to its actions. This divide-and-conquer approach allows Beijing to offer selective benefits while avoiding collective accountability.

Environmental destruction

The environmental consequences of China’s Mekong strategy are catastrophic. Chinese dams trap an estimated 96 percent of the river’s sediment flow, starving downstream deltas of nutrients essential for agriculture and fisheries. The once-mighty Mekong fishery—the world’s largest freshwater fishery—faces collapse as dam-induced flow alterations disrupt fish migration patterns.

Chinese sources acknowledge these impacts while attempting to minimize them. One official study admits that Chinese dams have reduced sediment flow by 94 percent but frames this as beneficial “flood control.”

The LMC provides diplomatic cover for this environmental destruction by creating forums for “dialogue” and “cooperation” that produce no binding commitments. China’s promises of “environmental protection” and “sustainable development” ring hollow when juxtaposed with the reality of continued dam construction and ecosystem degradation.

Economic coercion

The LMC exemplifies China’s neo-colonial resource extraction. It facilitates Chinese investment in downstream countries’ hydropower sectors, creating economic dependence while extracting electricity back to China. This arrangement serves Chinese energy security while locking downstream nations into disadvantageous relationships.

The LMC Special Fund, touted as a generous contribution of $300 million over five years, pales compared to the economic benefits China extracts from the region. Chinese state-owned enterprises dominate regional hydropower development, using favorable financing terms to secure long-term contracts that benefit Beijing at regional expense.

Furthermore, China’s “bundled” approach to aid, trade, and investment creates complex webs of dependence. Countries accepting Chinese hydropower investment find themselves obligated to import Chinese manufactured goods and sign trade agreements on Beijing’s terms, creating a comprehensive system of economic control masked as mutual benefit.

Bangladesh: the next victim?

Bangladesh’s dangerous inertia over the Brahmaputra River makes it vulnerable to the same predatory tactics China employed on the Mekong. With 91 percent dependence on trans-boundary water flows and the Brahmaputra contributing nearly 70 percent of its annual river flow, Bangladesh faces existential threats from Chinese upstream manipulation. China’s construction of the world’s largest dam on the lower reaches of the Brahmaputra—a US$167.8 billion project capable of generating three times the power of the Three Gorges Dam—represents a “water bomb” scenario for downstream nations. Yet Dhaka’s response remains inadequate limited to diplomatic protests and technical cooperation discussions.

Bangladesh’s recent collaboration with China on water management, including formation of joint committees and cooperation between research institutions, mirrors the early stages of Mekong countries’ integration into Chinese-dominated frameworks. While framed as beneficial technical cooperation, these arrangements risk creating the same dependencies that now plague Mekong nations. The parallels are striking: China offers technical expertise and funding for water management while constructing upstream infrastructure that grants it ultimate control over water flows. Bangladesh’s enthusiasm for Chinese assistance—including a 50-year water management master plan—suggests dangerous naivety about Beijing’s long-term intentions.

Learning from the Mekong’s tragedy

The Mekong’s experience offers crucial lessons for Bangladesh and other potential victims of Chinese hydro-hegemony. The LMC demonstrates how China uses multilateral frameworks to legitimize unilateral actions, environmental rhetoric to mask ecological destruction, and economic incentives to create political dependence.

Bangladesh must recognize that China’s offers of cooperation come with strings attached. The promise of Chinese expertise in flood management and smart water systems should be weighed against the risk of technological dependence and political manipulation. Most critically, Bangladesh should avoid the Mekong countries’ mistake of engaging with China through bilateral arrangements that prevent collective action.

Regional cooperation remains essential, but it must be genuine multilateralism that constrains rather than enables hegemonic behaviour. Bangladesh’s recent accession to the UN Water Convention represents a positive step toward establishing international legal frameworks for transboundary water management, but such frameworks require enforcement mechanisms and political will that have thus far proven elusive.

The LMC stands as a masterpiece of Chinese strategic deception—a wolf in sheep’s clothing that has transformed Southeast Asia’s most vital river into an instrument of Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions.

Bangladesh faces a critical choice: learn from the Mekong’s tragedy or repeat it. The time for reactive diplomacy has passed; only proactive regional cooperation with India and robust international legal frameworks can prevent the Brahmaputra from becoming another Chinese weapon disguised as opportunity.

Chandu Doddi is a research scholar in Chinese Studies at the Center for East Asian Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.