Indonesia will take over as chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in January, but that does not mean that the regional grouping will do anything decisive to end the crisis in Myanmar. ASEAN’s two basic principles — consensus and non-interference — make that a non-starter. But an initiative put forward by a group of Indonesian legal experts might have a profound impact on the fate of the junta that seized power in Naypyitaw in February last year. A case has been made by those experts to amend a law enacted in 2000 which restricts punishment for human rights violations to those committed only by Indonesian citizens. If it is accepted by the country’s Constitutional Court, Myanmar’s generals could be brought to justice in Indonesia.

Chapter XA of Indonesia’s constitution, which was written in the final days of World War II and at time when its nationalist leaders Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta declared independence from Dutch colonial rule, guarantees the protection of human rights to “every person”. However, Article 5 of the 2000 act says that Indonesia’s Human Rights Court can “hear and rule cases of gross violations of human rights perpetrated by Indonesian citizens outside the boundaries of the Republic of Indonesia.” The legal experts — Marzuki Darusman, a former attorney general, Busyro Muqoddas, head of legal affairs at Muhammadiyah, the country’s largest Muslim charity, and Sasmito Madrim, chair of Indonesia’s Independent Alliance of Journalists (AJI) — argue that the 1945 constitution does not mention the issue of citizenship and, therefore, upholds the protection of human rights universally. The experts want “by Indonesian citizens” removed from the law because they say that such wording contradicts the original constitution.

According to a press release issued by the THEMIS Indonesia Law Firm, Legal Aid Institution of Muhammadiyah and AJI on October 13, the court “has held its second hearing of a petition requesting a change in a law concerning the Human Rights Court. The move would allow cases to be heard in Indonesia against perpetrators of atrocity crimes in Myanmar.” The online hearing was heard by three justices of the nine-member Constitutional Court who were reportedly “very open” to the arguments of the petitioners. The case is still being reviewed and there will be a third hearing involving “the Plenary of the Constitutional Court”, which means all its nine judges.

After that, it is possible that the case may be heard by Indonesia’s parliament, which may or may not vote in favor of changing Article 5 of the 2000 act to be, as the three legal experts argue, in compliance with the 1945 constitution. But the very fact that the Constitutional Court has held hearings on the case has attracted attention in Indonesia.

In an opinion piece published by the Jakarta Post newspaper on October 12, Salai Za Uk Ling, the deputy director of the Chin Human Rights Organization, Antonia Mulvey, executive director of Legal Action Worldwide, and Chris Gunness, the director of the Myanmar Accountability Project, stated that it “will send a powerful signal to Myanmar’s generals — who have blatantly ignored ASEAN entreaties — that their actions are an embarrassment to a region that is striving for good economic and diplomatic relations internally and also with nations outside east Asia.” The writers went on to say that “should Indonesia’s Constitutional Court allow the case to be heard, this would be a win for Indonesian justice, a win for Indonesian diplomacy a win for ASEAN, and, more important, a win for the 55 million people of Myanmar.”

It is too early to say what the efforts will result in, and the generals in Naypyitaw have yet to react to what is going on in Indonesia, a country that endured decades of dictatorship before it could develop into Southeast Asia’s most vibrant democracy. That image has been tarnished by the passing on December 6 of a new criminal code that would ban sex outside marriage, cohabitation between unmarried as well as same sex couples, insulting the president, and “expressing views counter to the national ideology”, known as Pancasila, the five principles on which Indonesia was founded and that can be interpreted in different ways: divinity, humanity, unity, democracy, and social justice.

There have been public protests against the new law and Andreas Harsono, senior Indonesia researcher at Human Rights Watch, stated on the organization’s website on December 8: “In one fell swoop, Indonesia’s human rights situation has taken a drastic turn for the worse, with potentially millions of people in Indonesia subject to criminal prosecution under this deeply flawed law.”

But Indonesia’s civil society remains strong with very active human rights organizations and press freedom advocacy groups, making it doubtful whether that law can be implemented. Nor will it have any bearing on the petition now being brought before the Constitutional Court through an initiative taken by three prominent Indonesian citizens with impeccable reputations.

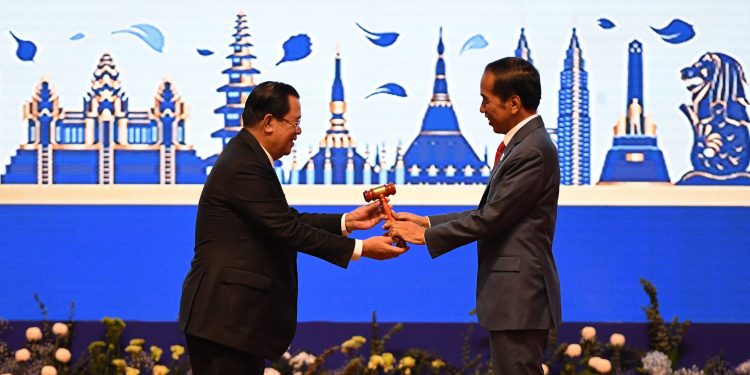

With Indonesia holding the ASEAN chair next year, the legal issue is bound to be discussed among other member states as well. ASEAN’s only effort to solve the Myanmar crisis so far has been the Five-Point Consensus, a peace plan adopted when coup leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing paid a brief visit to Jakarta on April 24 last year. It calls for a cessation of violence and “a constructive dialogue between all parties concerned.”

It was also decided that the ASEAN chair would appoint a special envoy to “facilitate mediation on the dialogue process”, and provide aid through AHA, the ASEAN Coordinating Center for Humanitarian Assistance on disaster management. All that has failed to materialize because ASEAN has no mechanism to implement such decisions taken by the bloc. ASEAN has only banned members of the junta from attending some vital ASEAN meetings. Most recently, the junta-appointed defense minister, General Mya Tun Oo, was not allowed to participate in a summit with Southeast Asian defense chiefs, which was held in late November in Cambodia, the current ASEAN chair.

ASEAN had previously banned the junta’s foreign minister, Wunna Maung Lwin, from two meetings earlier this year and also disinvited Min Aung Hlaing from its 2021 and 2022 gatherings. The military regime has reacted angrily to those very modest steps taken by ASEAN. Junta spokesperson Major General Zaw Min Tun lashed out at ASEAN after a previous snub, saying that the bloc was violating its own policy of non-interference in a country’s sovereign affairs while facing “external pressure”. But what so far has been only a shouting match could take a very different turn, and then outside of the ASEAN framework, if the case in Jakarta goes forward and makes it possible to try Min Aung Hlaing and his cohorts in an Indonesian court.