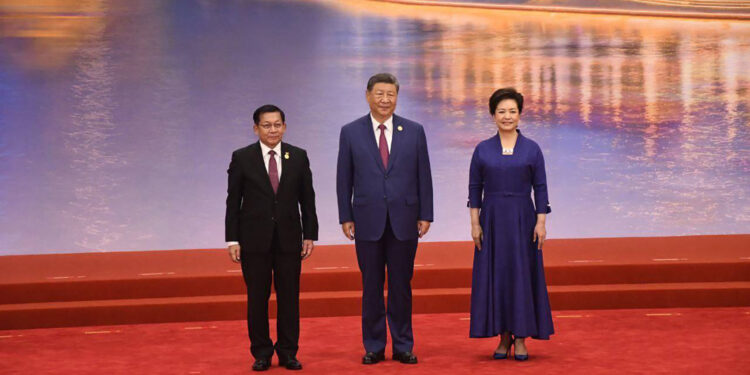

On Sept. 3, 2025, China hosted a lavish ceremony in Beijing to commemorate its victory over fascism. The event, intended in part to honor the victims of atrocities like the Nanjing Massacre, paradoxically featured Myanmar junta chief Min Aung Hlaing. His presence on the red carpet—despite his regime’s ongoing campaign of violence and repression against its own people—should be a moment of shame for all Chinese citizens.

Since Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to Naypyitaw in August 2024 after the fall of northern Shan State capital Lashio, Beijing has propped up Myanmar’s embattled regime with military, political, and economic support. For Min Aung Hlaing, who had endured diplomatic isolation for over four years, invitations to high-profile events like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Summit and the military parade in Beijing, along with ceremonial receptions, represent a major diplomatic victory.

China’s stance on the Myanmar junta

China intervened at a critical moment when Myanmar’s military was fracturing internally and resistance forces were gaining ground in northeastern battles. Some analysts believe that had Beijing delayed its support, it could have triggered leadership changes within the military and broader shifts in Myanmar’s political landscape.

Instead, China chose to back Min Aung Hlaing, helping him consolidate power.

Many believe that China’s support must stem from fears that Myanmar could descend into chaos if the military collapses, threatening Beijing’s strategic interests there. But the decision to embrace Min Aung Hlaing so publicly suggests a deeper motive.

Rather, it appears to be part of China’s strategy to cultivate the junta as a proxy force in its broader rivalry with the United States. By backing the regime, China secures a compliant government in a country that offers strategic access to the Indian Ocean: any shift in Myanmar’s military or political structure would therefore jeopardize Beijing’s ability to maintain such influence.

During Min Aung Hlaing’s recent visit, it became evident that the junta is willing to approve any project proposed by Beijing and is prepared to sell off any national resource at a discount rate in exchange for continued support.

The regime also appealed to China to pressure ethnic armed groups within Myanmar. Min Aung Hlaing openly expressed gratitude for Beijing’s assistance.

Having demonstrated its readiness to trade away Myanmar’s sovereignty for political survival, it would not be unexpected if the regime eventually ceded whole parts of the country to Chinese influence as well.

Proxy politics

China’s declaration during the Sept. 3 parade—that it, unlike the U.S., does not coerce or threaten other nations—rang hollow for Myanmar’s ethnic groups, who have faced increasing pressure from Beijing.

It is unlikely that China will sever ties with ethnic armed groups along its border in the way the junta desires. Instead, Beijing wants to use these groups as leverage to maintain control over the regime. The dynamic suggests that Min Aung Hlaing’s government will become increasingly dependent on China, evolving into a long-term proxy.

By cultivating ties with Min Aung Hlaing, China has provided the junta with tangible advantages. Its backing of a regime accused of widespread war crimes has emboldened the military to continue its brutal campaign—on the battlefield, in prisons, on city streets, and in rural villages—without fear of being held to account. The suffering of Myanmar’s people will only deepen.

Reports indicate that over 10,000 civilians have been killed and approximately 50,000 arrested since the 2021 coup. More than 100,000 homes, have been burned and destroyed.

In 2025 alone, the junta carried out 105 documented massacres, killing 1,081 people, according to the parallel National Unity Government (NUG). In July, a viral video showed junta troops in Mingun, Sagaing, beheading and dismembering a civilian accused of being a member of the People’s Defense Force (PDF). Eyewitness accounts have corroborated the footage, sparking international outrage.

When Beijing decided to back this regime, it realized that military and economic aid alone were insufficient. It began pressuring ethnic armed organizations near the border, cutting off supplies of weapons and essential goods until they complied.

The Myanmar military remains fragile. Yet, emboldened by Beijing’s support, the regime believes it is gaining the upper hand and is now attempting to annihilate ethnic forces. This will only prolong the civil war and intensify the suffering of Myanmar’s population.

China’s recent public endorsement has entrenched Min Aung Hlaing’s hold on power, shielded the regime from international accountability, undermined hopes for national reconciliation, and placed Myanmar’s sovereignty at risk.

China’s missteps

But the Chinese government made two major miscalculations in its Myanmar policy, and they stem from a foreign policy driven more by strategic interests than a genuine understanding of the country’s internal dynamics.

The first misstep occurred between 1967 and 1985, when Beijing provided military support to the Communist Party of Burma in border regions. This was motivated by strategic aims—countering Kuomintang and U.S. intelligence operations—and promoting global communist movements. However, the effort ignored the will of the Myanmar people and ultimately failed.

The second misstep followed the 2021 coup. China’s current engagement with the regime is widely seen as part of its anti-American cold war strategy, but again it runs counter to the aspirations of the Myanmar public and is therefore unlikely to succeed.

Despite China’s backing, the regime is riddled with corruption and mismanagement. The military is bloated with forcibly recruited soldiers but suffers from poor discipline and morale. Its widespread war crimes have only fueled public resistance.

China will likely reject these criticisms, insisting that its support for the junta is aimed at maintaining stability rather than interfering in domestic affairs. It continues to emphasize the importance of national reconciliation after elections.

But the junta’s actions show no genuine commitment to reconciliation. Only sustained pressure from China might compel the military to change course. Whether Beijing will push for peace or continue backing authoritarian rule will become clear by 2026.

(Thet Htar Maung is a political analyst)