Since the junta seized power, waves of people from Myanmar have crossed over to Thailand due to the intense armed conflict in their homeland. While their quality of life can certainly be improved, most of these people have adequately settled on Thai soil through various ways and means. Now as the conflict continues to deteriorate in most of the country, Myanmar is facing a multifaceted crisis that could trigger yet another cross-border movement.

While updates on its security concerns and armed conflict situation are ubiquitous, the economic standing of Myanmar is also worthy of discussion. Bottom line is, it is bad; so bad that the junta has been forced to develop some economic countermeasures. One such recent development is that the Central Bank of Myanmar (CBM) has deployed a series of incremental relaxations in the policy on foreign exchange, such as floating the kyat to the market rate, since around mid-December of last year, as it sought to incentivize market activities by bringing more foreign exchange into the domestic economy. On the flip side, the weakened value of the kyat compared to that of the overvalued official rate pegged prior to the policy changes could also lead to higher domestic prices for traded goods, making it more expensive for the ordinary Myanmar person to purchase products. Lurking in the background is also the low productivity rate of the private sector, rising consumer price inflation, and border trade losses due to armed conflict. The World Bank’s Myanmar Economic Monitor reported in December 2023 that the annual inflation rate in Myanmar is now at 29 percent as the kyat has depreciated by 18 percent against the US dollar; and that firms were reportedly operating at just 56 percent of their capacity in September 2023. Similarly, the Ministry of Commerce of the State Administration Council (SAC, the junta’s official name) recorded a 40-percent border trade decline, in the areas adjacent to both Thailand and China, since the beginning of Operation 1027, a major anti-regime military offensive launched in northern Shan State in October by an alliance of ethnic armed organizations (EAOs). Overall, the combination of instability from both the security and economic perspectives could potentially render Myanmar unliveable for its people.

On Feb. 10, 2024, several days after the third anniversary of the coup, the SAC reactivated the People’s Military Service Law of 2010. In essence, the law calls for mandatory conscription of the young generation of Myanmar people, aged 18-35 for males and 18-27 for females, to serve in the military for at least two years. Experts and analysts have made observations about this move of the junta and what it could be signalling to the world about its precarious position on the battlefield. They even noted that this effort of forced recruitment will eventually blow up in the junta’s face. Considering the aforementioned deepening of the socioeconomic crisis and day-to-day hardship, it is plausible that the conscription will add to the existing concerns of forced migration from Myanmar. Using data from the World Bank Group (WBG) on population, this essay offers a forecasting analysis of the implications of this new law with an emphasis on Thailand. Without a proactive plan to manage this potential wave of people, it will overwhelm the Thai border management mechanisms, making illicit human trafficking more likely.

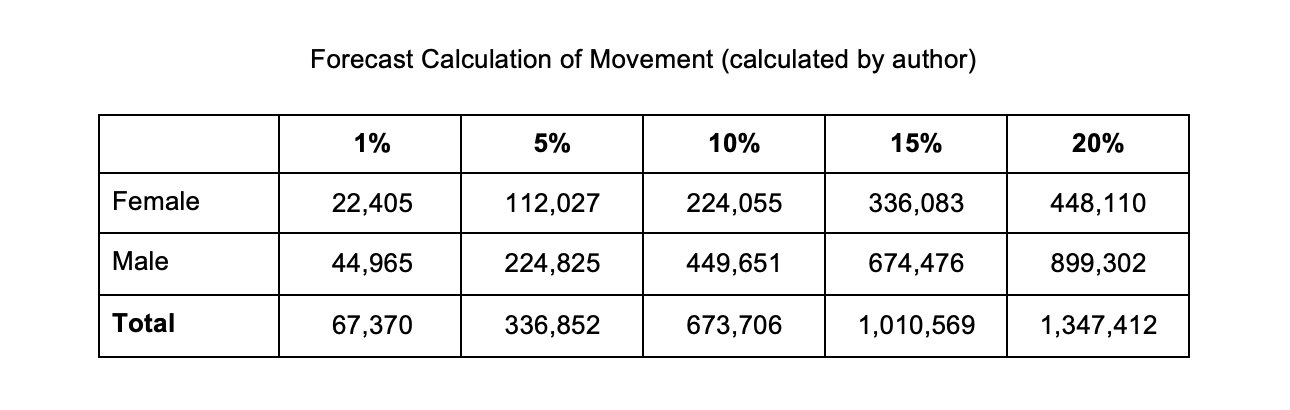

From the 2022 data, Myanmar has a total population of around 54 million. Based on the law, young men and women are the obvious target for recruitment. From the WBG data, which includes information on both the total male/female population as well as age group breakdowns, I recalculated the numbers to fit the law’s requirement as best as possible. Now, we are looking at approximately 2,240,553 females, aged 20-29; and 4,496,512 males, aged 20-34 who could potentially be drafted today. Obviously, a segment of these young men and women will resist and try to escape from the law. The most viable options for them are either to join the revolutionary groups (Peoples Defense Forces or EAOs) or flee the country entirely. For the second option, many observers have noted Thailand as the most plausible exit route, if not destination, since it is easier to reach than China or India. While we cannot be certain how many of them will choose to flee the country and cross the border into Thailand, a forecast figure should already raise the alarm for the Thai government. The table below shows a calculation of how many young-generation Myanmar people Thailand will have to manage if X percentage of them choose to flee from their homes.

While this calculation is capped at 20 percent migration, one gets the picture of how massive this movement could be. If only 1 percent of young Myanmar people choose to flee to Thailand, we are already looking at over 67,000 people waiting at our doorstep. This will add to the number of existing refugees and internally displaced people, posing a challenge for Thailand to manage despite the initiative to provide humanitarian assistance in Tak Province, particularly because this group of “potential arrivals” will be facing quite a different reality than the former groups—they have no home to go back to. The minute these people leave their homes, they are fugitives from the law who will face heavy punishment, or even death, if they get caught. Considering the international principle of non-refoulement means that we cannot push these people back, noting the imminent threat to their lives, it will present yet another complex layer for Thailand since different measures and assistance are needed for this group of people compared to the “immediate refugees” who are the IDPs in Myanmar’s ethnic-controlled areas sheltering temporarily in the designated temporary safety areas (TSAs) along the Thai-Myanmar border with restricted arrangements by the Thai authorities. Alternatively, these young men and women could be incorporated as migrant workers. According to the statistics from the Foreign Workers Administration Office of the Ministry of Labor of Thailand, there are already 2.1 million migrant workers from Myanmar registered to work in Thailand as of January 2024 through the two recent cabinet resolutions; however, some labor rights activists have disclosed that this number only reflects registrations, but not the completion of the process. This means that the Thai administrative system is already struggling to process the existing workers at hand, leaving many still in the pipeline without proper documentation to stay or work in the country. Consequently, the precarious predicament of migrant workers leaves room for them to be further exploited by opportunistic actors.

Overall, the Thai government should take note of the potential aftermath of the new conscription law issued by the SAC. Although the Thai foreign minister has said that “We will not interfere with their internal [Myanmar] affairs,” this enactment of a domestic law will have effects on Thailand. Just the sheer number of people who may try to escape the forced recruitment could overwhelm our border management mechanisms, and a humanitarian corridor will not resolve this issue due to the different realities and needs of the target groups. Without proper preparation and clear guidelines, local authorities, who find themselves overwhelmed by the movement of people, may resort to the usual tactics via immigration measures without regards to international human rights obligations. Even worse, it may contribute to the proliferation of the illegal human trafficking business since more people are now enquiring about the cost of migration to foreign countries online, adding more to the problem of organized crimes and transnational security that have been stifling the region.

As such, there is an urgent need to develop a proactive plan to prepare for the potential influx of the young people of Myanmar, who may have to seek refuge in our land for a prolonged period. For instance, a consultative dialogue with the revolutionary ethnic organizations from the Myanmar side to ensure conducive circumstances should be emphasized. Specifically, new administrative approaches such as a joint initiative that aims to promote liveability in the areas along both sides of border, allowing economic activities, employment, education, and public health provisions to thrive, could serve as an alternative for border management that can sustainably absorb this wave, and perhaps even future influxes, alleviating the administrative burden on Thailand’s status quo mechanisms.

Dr. Surachanee Sriyai is currently a visiting fellow at the ISEAS Yusof-Ishak Institute. Her research interests include digital politics, political communication, comparative politics, and democratization.