Faced with widespread armed resistance, Western sanctions and boycotts from some regional governments, the regime in Myanmar has aggressively stepped up and strengthened its diplomatic engagement with its few allies including China and Russia.

In danger of being outplayed, the exiled National Unity Government and opposition forces, including the ethnic leaders, are now in catch-up mode and have a lot of homework to do in this area.

China has opened its arms to the regime, which is eagerly forging ever closer and warmer relations with Myanmar’s giant neighbor. Beijing’s geostrategic and economic interests in Myanmar are far greater than those of India and Thailand, two other key countries that continue to engage with the junta.

The regime depends on aid, investment and military supplies from China, but reengagement also brings with it many challenges as Myanmar’s population overwhelmingly oppose efforts by other nations to lend legitimacy to the brutal junta.

The junta’s Foreign Ministry reported in February that China is funding 92 projects worth US$27.4 million in Myanmar through the Mekong-Lancang Cooperation Special Fund.

In August, at the Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS) Economic Corridor Governors Forum in Kunming, China, the junta’s Investment and Foreign Economic Relations Minister Dr. Kan Zaw told the gathered delegates that China has 597 investment projects in Myanmar worth a combined $21.863 billion.

In recent months, the regime has sent dozens of delegations to southern China to attend key economic conferences. Three key ministers—Kan Zaw, Information Minister Maung Maung Ohn and Commerce Minister Aung Naing Oo— have all made trips to China.

China also continues to provide a large amount of aid to the powerful Ministry of Home Affairs in Naypyitaw, which has used the funds to build a digital forensic lab and acquire speed boats.

Last week Myanmar’s ambassador to China asked Beijing to share advanced nuclear technology to be used in Myanmar’s agriculture, health and energy sectors.

Self-interest

Myanmar has descended into a state of near civil war since the coup, but Beijing continues to engage the war criminals in Naypyitaw while defending them before the UN Security Council.

On the ground, Beijing is building a railway linking Kyaukphyu in Rakhine State with the key border town of Muse in Shan State via Myanmar’s second-largest city, Mandalay. The railroad is part of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor—itself part of China’s vast, international Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—and Beijing is also expanding investment in oil and gas pipelines in Myanmar, as well as tin, copper and rare earth mining, electricity production and border trade.

Engagement with China’s southern region became more active after Wang Ning, a member of the Communist Party of China (CPC)’s Central Committee and secretary of the CPC’s Yunnan provincial committee, met Min Aung Hlaing in Naypyitaw in April, signing agreements on rice, agricultural produce and fertilizer trade, and power purchases. In this case, the Yunnan administration took the lead, with no direct engagement between Naypyitaw and Beijing.

Under the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) forum, China has aggressively forged closer ties with the regime, creating uneasiness among Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) governments, as the regional grouping continues to ban the junta’s top leaders and foreign minister from its annual conferences and summits.

At the same time, the regime has used the China-ASEAN forum, which is held in China, as a venue to engage members of ASEAN, affording it a degree of legitimacy.

Next month, China will celebrate the 10th anniversary of President Xi Jinping’s BRI, marking the occasion by hosting the third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing. There has been speculation that Min Aung Hlaing will be invited to attend the forum. Should he do so, China and the junta’s cooperation will only be strengthened. It would also signal that China has finally jettisoned its cautious approach in favor of open and full engagement with the brutal regime in Naypyitaw.

Increasingly concerned with instability on the border, Beijing has stepped up collaboration not only with the regime but also with ethnic armed organizations operating on the frontier, stepping up cooperation on security and other border issues such as transnational crime, including online fraud and gambling syndicates, and collaboration between the two countries’ police forces has been enhanced.

Chinese shadow over election plans

Aside from economic engagement, senior members of the junta-appointed Union Election Commission (UEC) visited China recently. Junta media said the Myanmar delegation would observe the CPC’s efforts at state-building and party-building in China, a one-party state where elections are nonexistent.

UEC chief Thein Soe also made a separate visit to Russia.

In the first week of September, junta boss Senior General Min Aung Hlaing told his cabinet that he plans to hold an election after a national census in October next year, indicating that the poll will not take place until at least 2025.

Interestingly, in July, Thein Soe observed elections in Cambodia, held soon after the main opposition party was banned. The poll was criticized by the world’s democracies as neither free nor fair. Critics said it was nothing more than legal cover used by Hun Sen—then one of the world’s longest-serving leaders—to hand power to his son, Hun Manet, who became Cambodia’s prime minister last month.

In any case, last week, in his first foreign trip as head of government, Hun Manet visited China and met Xi, signaling that the transition would do nothing to disrupt Cambodia’s status as one of Beijing’s staunchest allies in Southeast Asia, in return for which it receives huge sums in Chinese investment.

Chinese leaders were impressed by Hun Sen’s deft management of the election in Cambodia and have presumably conveyed a message to the junta leaders in Naypyitaw to organize their long-promised vote in Myanmar. Western countries insist no election held under the junta could be free or fair. Does China want to see the left hand turn over power to the right hand in Myanmar? Would it be wishful thinking to believe that China will use its influence under its stepped-up engagement with the junta to push for an election that would lead to a transition to some form of civilian government?

Friends in Russia, Belarus

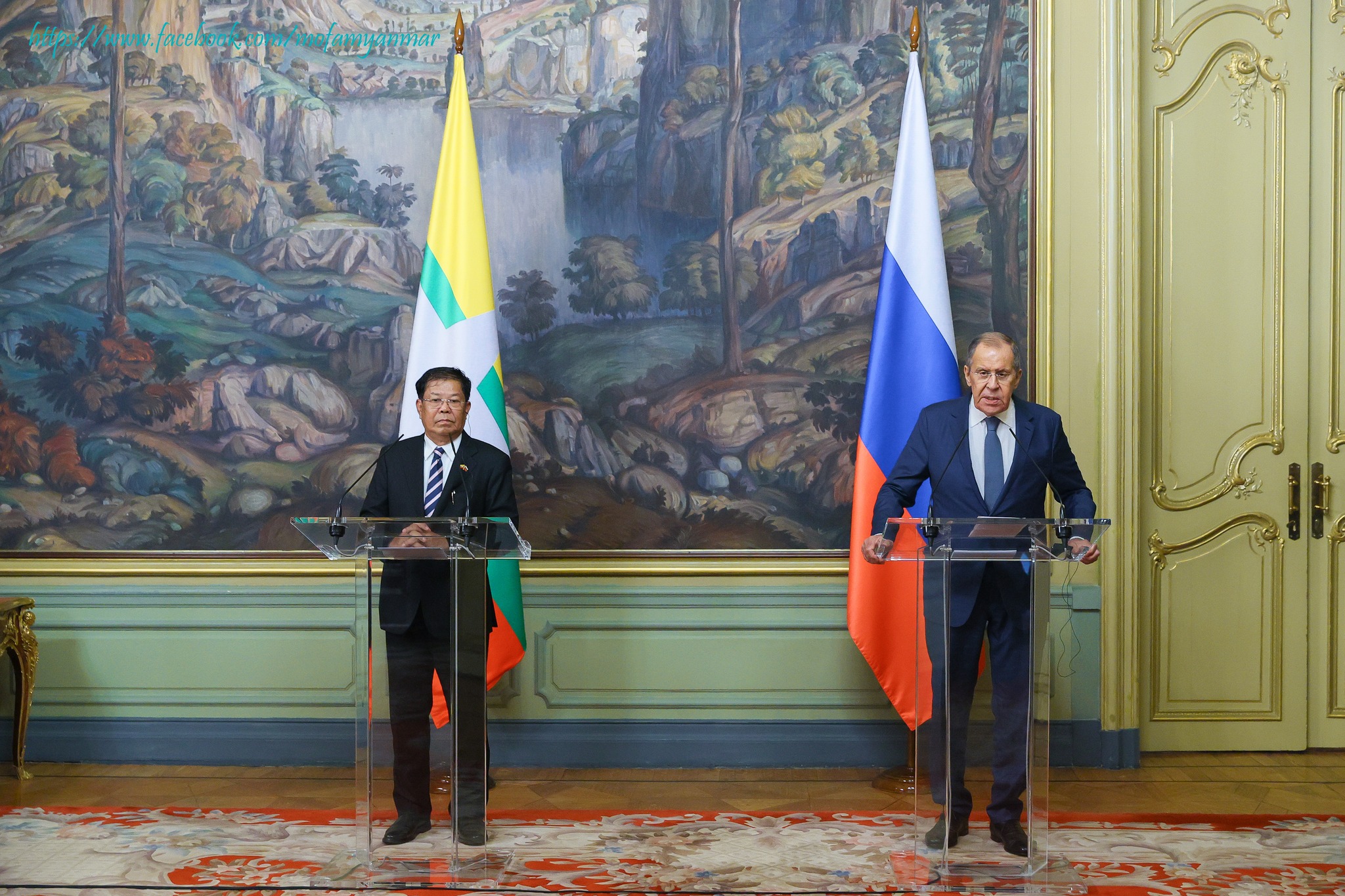

Beijing is not alone in strengthening its friendship with the regime in Naypyitaw. This month, junta Foreign Minister Than Swe visited Russia and met with his counterpart Sergey Lavrov. Than Swe told a press conference that relations between the two pariah nations were at a new peak and that he understood the current situation in Russia.

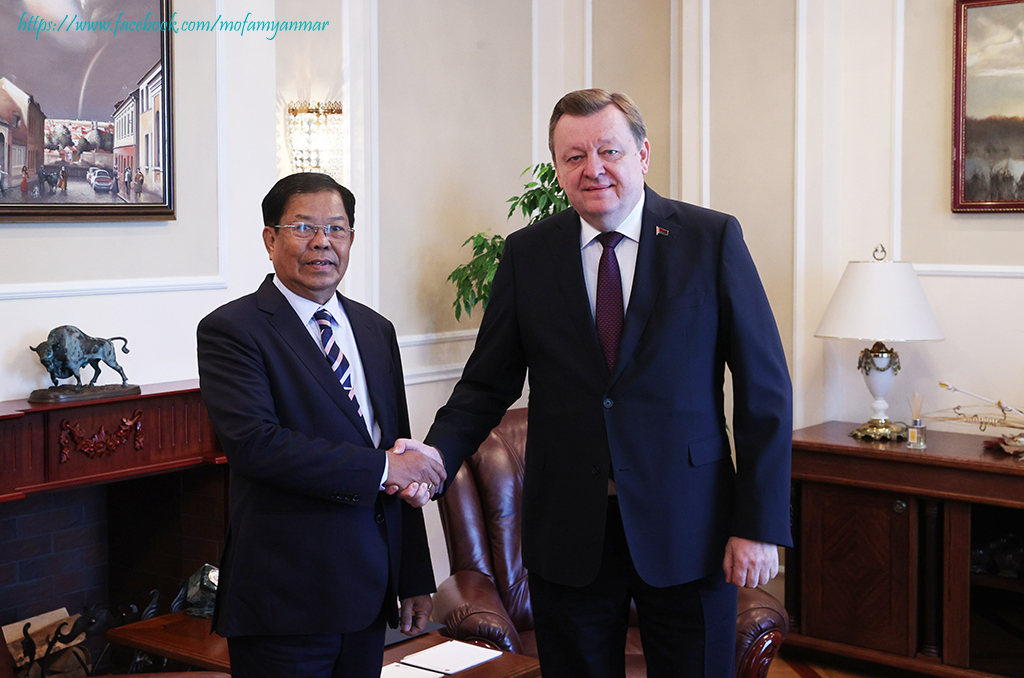

Expanding ties with another Eastern European friend, the regime opened a consulate in Belarus’ capital Minsk this month. Russia and Belarus are major arms suppliers to the regime. Russia has always been supportive of the regime at the UN and Belarus has also refused to join other members of the world body in condemning the military coup.

The junta has also renewed its old friendship with North Korea, recently appointing a new ambassador to the isolated country. Tin Maung Swe, the regime’s ambassador to China, will concurrently serve as envoy to North Korea. In the past, the US had expressed concern over Pyongyang’s continuing efforts to provide weapons to the junta.

However things unfold, as mentioned earlier these efforts to foster ties will bring challenges. In Myanmar, anti-Chinese sentiment is running high as Beijing has repeatedly supported the regime on the global stage while also selling it weapons worth millions of dollars to use in its brutal crackdown on opponents of military rule. Chinese projects have been targeted in Myanmar since the coup.

Politically and in terms of human rights, democratic and opposition forces in Myanmar draw inspiration from the West, something that elicits mistrust from China. There is very limited communication between Beijing and Myanmar’s democratic forces, though China continues to engage ethnic armed groups on the border, pressuring them to enter dialogue with the regime. However, it is very unlikely that ethnic forces are going to strike any formal ceasefire or agreement with the Myanmar military for the time being.

Beijing, Russia and Belarus’ stepped up engagement with the regime in Myanmar will not win the hearts and minds of the majority of Myanmar people. For that reason, their engagement will necessarily remain limited, uninspiring and one-sided, based as it is on narrowly focused strategic self-interest.