As the saying goes, “Truth is bitter.” But we must face these bitter truths if we want to avoid deception, abandon illusions and act practically to solve our country’s chronic political crisis.

Let’s swallow that bitter medicine. This is about diagnosing a deep-rooted disease that has plagued Myanmar for over a century. I call it “Myanmar’s 60-Year Political Cycle.” Why? Because our country has already endured 60 years under colonial rule and another 60 years under military dictatorship. The question now is: What comes next?

Can Myanmar finally become a peaceful and stable nation after breaking free from military rule? When, and how, will we escape it?

The first 60-year cycle: British colonialism

To understand where we’re going, we must look back—not only at political systems, but at global events like the world wars and the rise and fall of empires.

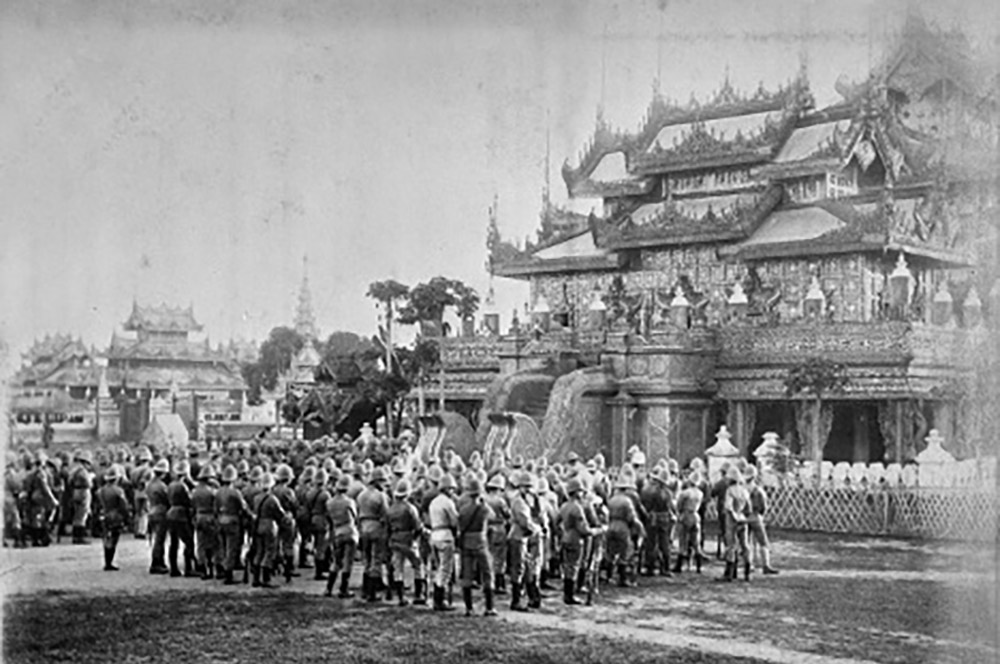

Let’s begin in the 19th century. On November 28, 1885, after the Third Anglo-Burmese War, British forces captured the Mandalay Palace and forced King Thibaw to abdicate, formally annexing the whole country on January 1, 1886. At the time, our ancestors could not have imagined the colonial yoke would last more than six decades.

But the resistance began early, during the first and second Anglo-Burmese wars in 1824 and 1853. Armed uprisings sprang up and rebel leaders like Bo Min Yaung and Saya San were executed. The nationalist movement later took shape under Thakin Kodaw Hmaing and passed into the hands of student leaders like Ko Aung San and U Nu. This eventually led to the formation of the Burma Independence Army and the long struggle for independence.

Like many Asian nations during the era of colonial expansion, the fate of Myanmar (known as Burma at the time) was shaped by the global trend of imperialism. The British ruled the entire country from 1886 to 1948—a full 62 years.

The first opportunity to remake the country

Myanmar got a chance to remake itself when it regained independence in 1948. Under Prime Minister U Nu and the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), the country enjoyed political freedom, vibrant democracy and one of Asia’s most promising economies, while undergoing political changes as a fledgling nation. This young nation with parliamentary democracy lasted about a decade.

But when General Ne Win seized power in 1962, that window closed. Myanmar’s first opportunity to remake itself lasted just 10 years before being cut off by its first coup, which was followed by authoritarianism.

The second 60-year cycle: military rule

The seeds of dictatorship were planted even earlier, when Ne Win assumed leadership of a caretaker government in 1958. Though power was briefly returned to U Nu in 1960, Ne Win’s 1962 coup launched a formal military dictatorship.

His one-party system under the Burma Socialist Programme Party ruled for 26 years. If we include the 1958–60 caretaker period, the country spent 28 years under Ne Win’s military boot. After the 1988 uprising, the military retained power under the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) and later the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC)—until 2011. Then came a pseudo-civilian government under former general Thein Sein, elected through a manipulated 2010 vote boycotted by major pro-democracy parties.

From 1958 to 2016, Myanmar spent nearly 58 years under military rule, led entirely by generals or their proxies. That was our second 60-year cycle.

The second opportunity to rebuild

In 2015, the National League for Democracy (NLD) won a landslide victory in a relatively free election. In 2016, for the first time in more than half a century, an elected government took office.

This was our second chance to remake the country—but it lasted just five years.

Had the military allowed this period to go on, the country could have evolved into a stable democracy. Economic growth, peacebuilding and social development were all within reach. We might have ended the 60-10-60 cycle, entering a new era of sustainable democracy.

But on February 1, 2021, the generals struck back again—staging a coup. They nullified the 2020 election results, and arrested the country’s elected leaders. And the country lost another rare opportunity to rebuild—the only opportunity in a century.

Looking back from 1886 to 2021, we now see the pattern more clearly than ever: 60 years of colonialism → 10 years of rebuilding → 60 years of dictatorship → 5 years of fragile democracy → another era of military dictatorship.

If this pattern continues unbroken, the next cycle could last until the 2080s or beyond. But this time, something is different.

Resistance: Can the people break the ‘curse’ cycle?

Since the 2021 coup, the people of Myanmar have shown unprecedented resistance. What began as peaceful protests has transformed into a nationwide revolutionary movement involving civil disobedience, political uprising and armed resistance.

The “Spring Revolution” is not limited to one generation. Gen Z, Gen Y, Gen X—and even older and younger generations—have all taken part. The uprising spans territory from major cities to the country’s ethnic borderlands. Ethnic armed organizations have found common cause with new resistance forces, including People’s Defense Forces. Their collaborative operations like the Operation 1027 military offensive have shown that the military is not invincible.

This is the strongest and most coordinated pushback against authoritarianism since 1962. The question now is: Will it succeed?

The final battle? Or just another cycle?

For the first time, we have a real shot at ending this 60-year cycle. But the military is regaining ground with support from some neighboring countries, especially China. With China’s quiet pressure on ethnic armed groups, it has begun recapturing lost towns like Lashio without major battles. Rather than compromise, the junta may be relying on diplomatic manipulation and divide-and-conquer tactics.

So, how do we break the cycle?

- Can armed revolution alone defeat a deeply entrenched military?

- Is a negotiated political settlement even possible, given the military’s refusal to compromise?

- Could international pressure—economic, diplomatic or legal—tip the balance?

We don’t yet have clear answers. Countless people, especially young people, have sacrificed for this cause since the coup. But one thing is certain: the outcome of this struggle will define Myanmar’s political future for the rest of the century.

Myanmar’s people are trying to do what has never been done before—to end the pattern and rewrite the future.

The struggle today is not just about removing a dictatorship. It is about finally breaking free from a cycle that has haunted us since the 19th century.