Life has been harsh for young Karenni woman Maw Thea Myar since she fled to a new camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) set up inside Thai territory near the Myanmar border.

The 20-year-old was forced to flee her previous IDP camp in Hpruso, where she had settled down with her sister’s family two years ago, after it was annihilated by junta bombs in an air raid in July 2023.

“I was just about to finish my diploma course. I thought I was going to achieve my dreams this year, but they were shattered by the junta bombing on July 12,” she said.

Life is a struggle for the more than 3,000 people living in the IDP camp, which is without electricity or internet access, lacks sufficient water supplies and is plagued by poor sanitation.

Yet these hardships haven’t broken her spirit; she still aspires to become a female leader for the Karenni people in the future.

She was taking a Community Development course offered by a local community college at Hpruso IDP camp before it was bombed. The lack of access to education at the new camp has been difficult for Maw Thea Myar, who sees it as the single biggest hardship she faces at the new IDP camp.

“The Thai authorities haven’t allowed our college to reopen in the new camp. So, some students have left the camp. Sometimes, I even have to hide my books,” she said.

“I am looking for a way to join another education center,” she said of her plans for next year. Her greatest hope is that her previous school will reopen, as it served as a beacon for ambitious Karenni youths like her who strive to realize their dreams of making a better future for their community.

Maw Thea Myar isn’t the only student who has refused to allow the flame of hope to be extinguished, and continues to seek a path of learning even amid all the uncertainty that now shrouds Kayah state.

Khu Moe Reh, 21, is also searching for an opportunity to join a GED (General Equivalency Diploma) course near the Myanmar-Thailand border.

After serving two years in the armed group the Karenni Nationalities Defense Force (KNDF), he decided to return to the classroom and take responsibility for supporting his family.

“My elder and younger brothers are KA [Karenni Army] and KNDF members. I urged my teenage brother to study again but he insisted on continuing to fight junta troops on the frontline. Our family needs one of us to support them in the future. So, I decided to study again,” he explained.

Opportunities are few and far between, however, as there are only a few education centers that can provide GED and higher education for IDPs, and the number of places they offer is extremely limited.

“Only one or two students will get the chance to study there. So, the competition will be fierce,” he said.

Since the military coup, nearly 10 million students across Myanmar have boycotted the regime’s education system and refused to return to classrooms and schools.

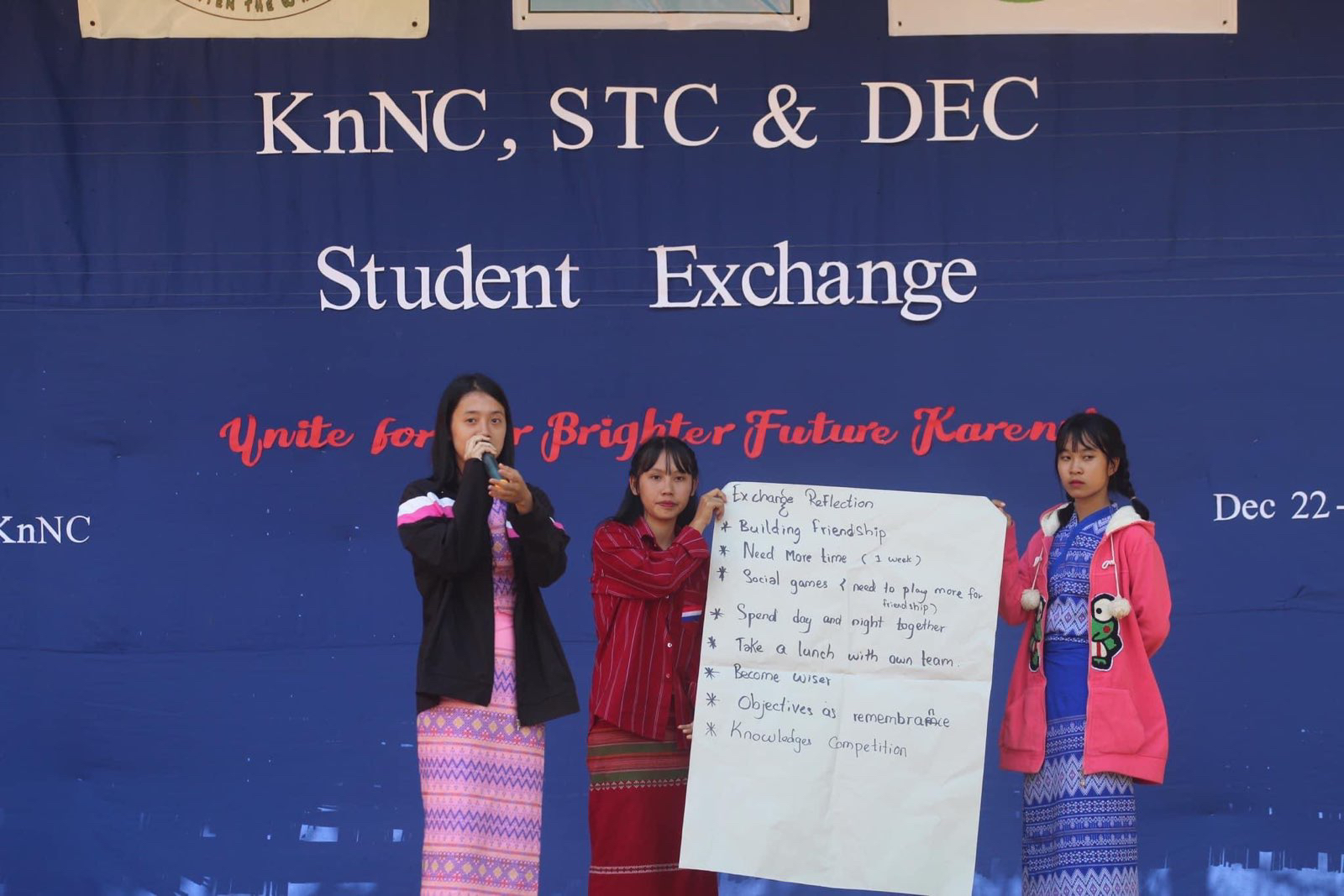

This has led Karenni youths to rely on local community colleges, which were founded by the Karenni Education Department in the 1990s to provide alternative educational opportunities for youths other than the government education system. A few colleges relocated to the Thailand-Myanmar border when fighting between the junta infantry and resistance forces intensified in the state.

The majority of Karenni people have become IDPs since a local armed uprising against the military regime broke out in the state in May 2021.

Daw Maw Mi Mar, spokesperson for the Karenni Education Department, said that in terms of education, Kayah State faces greater challenges than other resistance strongholds and territories controlled by ethnic armed groups.

“Our state is the smallest state, and clashes are breaking out everywhere. Nearly all schools are set up in IDP camps, which are regularly targeted by junta bombing and shelling,” she said.

Despite the loss of opportunities in higher education, basic education is still thriving in the IDP camps that dot war-torn Kayah State, each one a sea of blue and green makeshift dwellings.

CDM teachers and volunteers continue to ignite the spark of curiosity in children and guide them down the path of knowledge and learning, despite the fear, hunger and ongoing war that surrounds them.

The top priority for Daw Htar Htar, a volunteer teacher from Demoso, is to create a safe learning environment for her students after her school was bombed by a junta jet fighter on July 4.

She has been teaching at a typical makeshift school, covered by tarpaulin sheets, in a displacement camp in western Demoso since she joined the many CDM (Civil Disobedience Movement) teachers refusing to work under the military regime following the 2021 military coup.

The school started by offering primary education classes, Daw Htar Htar said, and this year expanded to provide secondary education.

“Apart from the shortage of teaching materials and learning aids, we need safe shelter with a secure and solid roof that can ensure safety and protection,” she said, adding that she had submitted a request for a proper roof as a long-term solution.

However, her request was denied by the volunteer groups assisting the camp for several reasons.

“It is not easy to donate zinc roofs due to the lack of funding and transportation difficulties. The number of students is also a factor,” a representative from a volunteer group explained.

Around 120 such makeshift schools are scattered across western Demoso Township. They are frequently struck by the junta’s indiscriminate shelling and aerial bombardments despite being far from the front line, where allied anti-regime forces are fighting regime troops seeking to advance into their territory.

Thanks to the efforts of the CDM teachers, most primary and secondary students in Kayah State have been able to continue their education without interruption in community schools set up by the teachers in displacement camps. However, high school instruction has noticeably declined within the state, educators said.

Upwards of 10 percent of the 226 schools set up by CDM teachers in Kayah offer Grade 9 classes or higher.

“Many youths have left for foreign countries to find work and others have joined the resistance forces, but I think education is also very important for them. We need to create an environment that creates other opportunities for our youths via higher education programs,” a volunteer teacher said.