When one of his Burmese colleagues showed him an official notice saying he had only six months to leave Myanmar’s most notorious cyber-scam hub – Karen State’s Myawaddy Township – Joel (not his real name) felt a surge of nausea that had become as familiar to him as the sweat he broke out in after arriving in Cambodia 16 months earlier, during one of that kingdom’s most humid months.

He had been told he was arriving for a high-paying managerial job at a call center for a Western credit-card company. Instead, he was driven by van from Phnom Penh International Airport to a concrete enclave near Cambodia’s border with Vietnam.

The first stab of nausea arrived when he saw soldiers wielding AK47s at its gates: It rippled through his entire body.

Less than a year later, Joel was sold to a scam center in Myawaddy.

One day after reading the nausea-inducing notice ordering him to leave Myawaddy, he shrugged it off, saying: “At least it gives me six months to pay off my debt.”

He took solace, too, in the fact that the militia that guarded the compound he was captive in, the Karen National Army (KNA)—previously known as the Karen Border Guard Force (BGF)—was the same one telling workers like him to leave.

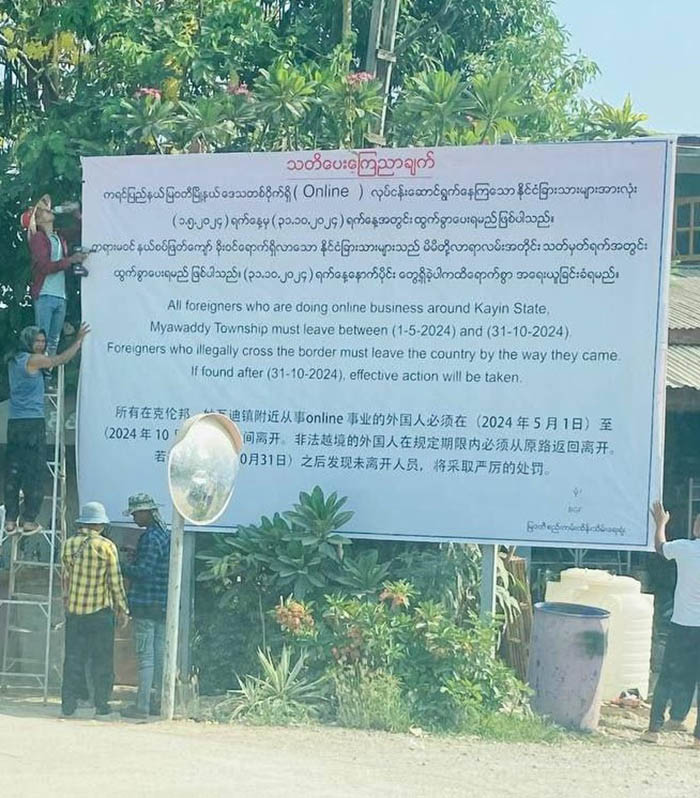

This was on May 2 when the KNA erected billboards in Myawaddy announcing in three languages—Burmese, Chinese and English—that foreign “online” workers were required to leave the township by the end of October.

Notices were also delivered to the countless online casinos and scam centers in the township with the same unambiguous message: “All foreigners who are doing online business around Kayin [Karen] State, Myawaddy Township, must leave between (1-5-2024) and (31-10-2024).

“Foreigners who illegally cross[ed] the border [into Myanmar] must leave the country by the way they came. If found after (31-10-2024), effective action will be taken,” the notice shown to Joel by an alarmed Karen colleague concluded.

Joel was under the impression that the KNA was the revolutionary army fighting for greater autonomy in Karen State and freedom from Myanmar’s barbaric military.

He was wrong.

The KNA is a junta-allied militia with a well-documented history of savagery that may only be exceeded by its leader’s – Colonel Saw Chit Thu (also known as San Myint) – monumental avarice, a report by Justice for Myanmar, an advocacy and research group, details.

As the Karen National Union’s armed wing, the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), drove Myanmar’s military from Myawaddy in late April the colonel and his mafia militia moved in.

The junta-allied warlord intervened on behalf of the near-defeated Tatmadaw to protect his business empire, including his financial connections to the 18 to 20 cyber scam compounds in the township, sources in Myawaddy and across the river in Mae Sot, Thailand, said.

Three weeks after the billboards went up, Joel – despite being further in debt – was even more upbeat: “Nothing has changed at work,” he enthused, explaining that his boss “looked into” the announcement, was “not even bothered” and “was confident to ignore it … [because] the colonel will protect us.”

Money matters

An April 22 report by the United States Institute of Peace in April estimated that Colonel Saw Chit Thu and his militia earn about US$192 million annually from a single scam compound in Myawaddy: Shwe Kokko. Last year, scam centers in Myanmar raked in $15.3 billion, the institute said in a May report. Combined, they employ – or enslave – more than 120,000 people, according to a 2023 report by the UN’s Human Rights Office.

More than $100 million has been traced to a single crypto wallet used by scam centers in Myawaddy scam compound KK Park so far this year, according to an August 29 report by Chain Analysis, which monitors cyber crime.

Researcher Nathan Paul Southern was not surprised by Colonel Saw Chit Thu’s moves in Myawaddy.

“Colonel Saw Chit Thu is running nothing short of a mafia organization involved in scams, human trafficking and drug trafficking. Operations are in no way slowing down,” he told The Irrawaddy.

“I can’t stress enough how the Cambodian and Lao governments, the Myanmar Tatmadaw or [Border Guard Forces] are making no effort to substantially crack down on this [regional crime],” Sutherland added. He is the operations director at Eye Witness Project, a London-based research consultancy that investigates conflict, crime and corruption and has conducted research for the US Institute of Peace on scam centers across Southeast Asia.

Southern offered a revealing anecdote: “Earlier this month [August], the Karen National Army organized a prayer service for notorious Chinese criminal kingpin She Zhijiang. The service involved hundreds of people and was wishing for the good health and release of one of the key architects behind … Shwe Kokko and [scam compounds] across the region.”

Jason Tower, Myanmar country director for the United States Institute of Peace, said that hundreds of members of the KNA who attended the “prayer service for the return of mafia boss She Zhijiang to [their] crime zone” were wearing shirts emblazoned with his image.

Mood swings

By late June Joel was alternating between extreme self-flagellation and giddy optimism. From his third floor office in a building Myawaddy’s Yu Long Bay, a gated and guarded scam compound on the edge of Myawaddy town, he looked wistfully towards Thailand and what he imagined was the freedom awaiting him there.

Some days he spoke about revising his CV to apply for English-teaching jobs in Bangkok.

(Joel’s nationality and age are not being disclosed to protect him.)

The scam center he works at targets victims in the United States and Canada with fake crypto currency investments. His job is to help close scams after “Burmese staff build a rapport” with potential victims. He’s what is called a “model” in the crime: a charismatic young man or woman who speaks the language of the victim and – once they’re primed – can reassure them into “investing” via a video chat on Telegram.

Joel’s employer keeps his passport locked in a filing cabinet. He also keeps a ledger of the ever-increasing costs Joel accrues in Myanmar, which began with the expenses of transporting him to Yangon from Cambodia and then to Myawaddy. (These costs do not include the fee his current employer claims he paid his Cambodian employer to buy Joel from a one-year contract.)

According to a section of a ledger obtained by The Irrawaddy, Joel owed slightly more than US$900 in May. Three Chinese nationals owed almost $9,000 combined. (The numbers are imprecise to avoid the risk of identifying them.)

The ledger lists seven costs captives must pay to gain their freedom: 1) passport and invitation letter; 2) six months visa; 3) labor certificate; 4) daily necessities; 5) plane ticket; 6) landing visa/return form; and, 7) fare (transport from Yangon to Myawaddy).

Other costs are added monthly, for air conditioning in dorms and hot-water showers, additional food and toiletries, as well as 5 percent monthly interest on the total. By the end of the month, Joel has nothing left from his $600 salary for working 74 hours a week, mostly at night under fluorescent tubes.

But even if he could pay the debt, he’s trapped in Myawaddy. He cannot cross either of the two “Friendship” bridges that span the Moei River linking the town to Mae Sot without being arrested in Thailand for illegal entry and deported home penniless. Leaving Myawaddy in the opposite direction could be fatal. The main road linking it to Yangon weaves through the Dawna Mountains in western Karen State. It is a war zone.

Some small nongovernmental organizations in Mae Sot are helping a trickle of people like Joel escape scam centers in Myawaddy. They lack the funding and resources, however, to do much.

Sutherland says the rescues are “unfortunately necessary” because law enforcement in the region does not do its job. “It is depressing how well we know the routes used by the traffickers time and time again and nothing stops them,” he explains.

There’s also more than a bit of theater to the rescues, which do succeed in convincing some that progress against cyber crime is being made.

Colonel Saw Chit Thu and his militia “are trying to make some public comments about cleaning up the areas under their control and [conducting] what are usually sham raids in order to appease the Chinese government,” Southern explains. “It’s important to remember that this crackdown [pushed by China] is really only on the scam compounds targeting Chinese victims and those, to a lesser extent, that use Chinese forced labor,” he adds.

“Mostly, the bosses are alerted to raids before they happen and as long as they switch to non-Chinese scam victims, such as those in the USA, UK or Australia, then they will be allowed to re-open again,” he explains.

“Scams and the human trafficking used to fuel them are not going anywhere under KNA control in the foreseeable future and it is important to remember that they are closely linked with the ruling junta. The cash being made in places like Shwe Kokko is an absolute necessity for the military to continue waging a horrendous war on the people of Myanmar.”

Three Pagodas

Sources in Mae Sot and Myawaddy say some staff are being shifted from scam centers to new ones in the southern tip of Karen State, near the Three Pagodas Pass, which crosses the border from Sangkhla Buri in Thailand’s Kanchanaburi Province to Karen State’s Payathonzu town.

One source in Payathonzu said they are primarily Chinese nationals, not captives but casino and scam center operators and managers. Scam centers and casinos in Payathongzu dwarf those in Myawaddy in size and number, but sources in Payathonzu say they are rapidly expanding in both size and number.

The town is mainly controlled by the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA), a narcotics- selling offshoot of the KNU, but that Colonel Saw Chit Thu’s militia is strengthening its hand there, and partnering with the DKBA to expand scam centers, sources in the town say.

Burmese media reports from Payathongzu say the influx of Chinese scam centers and casino operators has been so massive since April that rental prices have more than doubled, and that notices are now issued in both Burmese and Chinese. Land is being snapped up, too, on the hillsides around the town.

Chinese scam center operators are hiring bodyguards from the DKBA as well as Colonel Saw Chit Thu’s militia, according to Karen media.

The Chinese criminals are arriving from both Myawaddy by car and by strolling through the pass from Thailand waving Thai passports at immigration officials, Burmese media reports say.

They openly carry weapons in the town, the reports say.

Tower says it’s worse. The entire Myanmar side of the Moei River, which separates Karen State from Thailand, “has been overrun with criminal scamming compounds.”

“Scam syndicates in the DKBA territory are growing very quickly, as the DKBA has built a deeper alliance with Chinese crime groups. Larger numbers of non-Chinese trafficking victims are being brought in to the DKBA compounds like Taichang,” he explained.

Yangon calling?

Myanmar’s largest commercial city is also experiencing a scam-center boom. Residents and researchers identify the area around Times City in Ward 7 as a hotbed.

“The job ads are as sneaky as the scams,” one applicant for a scam center job near Times City said, requesting anonymity.

Southern said he just returned from Yangon and the scam compounds there are definitely on the rise.

“I can’t confirm yet whether or not they are using forced labor to run them. But even if they are not, then Yangon is likely to follow the same model as most other places where this has spread,” he added.

“Eventually, it becomes about economies of scale on scamming and a willing workforce is simply not able to contact enough people as hordes of slaves are.”