In an upscale residential complex situated in Hlaing Tharyar Township in Yangon, the commercial capital of Myanmar, Sophia and her team were busy scouring chat apps on their computers, relentlessly searching for gullible men to scam.

Logging on to a social media platform, Sophia initiated her daily routine by sending out a barrage of introductions to men hailing from countries like the United States, Spain and Canada.

Introducing herself as a Myanmar-born woman living in the US, Sophia told her interlocutor that she was currently on a business trip in his country—the first seemingly innocent step in a swindle aimed at persuading him to “invest” in a nonexistent cryptocurrency.

“Sophia” is not a woman, but a fake online identity used by Ko Oo, a 28-year-old man from Yangon in his job—scamming.

Ko Oo was laid off by a microfinance company in southern Yangon after the 2021 military coup as his employer struggled to recover loan payments from borrowers in the post-coup economic crisis.

After months of unsuccessful job hunting, he ended up working as a waiter in a restaurant located in Shwe Kokko—a so-called “new city” project in Karen State’s Myawaddy that has gained notoriety over the past year as a fraud park. He was offered a monthly salary of 400,000 kyats (US$190) for the job.

During his time working at the restaurant, he gained some knowledge about online scam syndicates and even got acquainted with some scammers.

After spending five months in Shwe Kokko, he had to return to Yangon due to family issues. However, he felt compelled to join a scam center due to the lack of other employment opportunities. The scam center, located in the Nawaday Garden housing estate in Hlaing Tharyar Township, is officially registered as a tech company called Global Cyber 8.

“When I was in Shwe Kokko, [those working at scam centers] asked me if I wanted to work as a scammer for a salary of around 15,000 [Thai] baht [$420] for a six-month contract. Some of my friends advised me not to take up the job, as they had heard that workers are subjected to torture there. So, I didn’t join a scam center. However, when I returned to Yangon, I struggled to find a job. Eventually, I ended up taking a job at Nawaday [Garden estate],” he said.

Every day, Ko Oo had to search social media platforms such as WhatsApp to find accounts and phone numbers of 28 potential targets, mainly from the US and Europe. He used various fake online identities including “Sophia”, “Emily” and “May”.

“When obtaining phone numbers, they avoid targeting those from China and other Asian countries. We then forwarded the data to experienced seniors, who handled the potential victims,” he said.

It appears that Beijing’s vigorous crackdown on online fraud has discouraged his employer from targeting Chinese citizens, Ko Oo suggested.

Myanmar was already facing economic challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic when the military staged a coup in 2021, causing further economic turmoil. Consequently, many Myanmar citizens struggling with high unemployment and skyrocketing food prices are turning to scam centers that promise high-paying jobs, just to make ends meet.

Many young people from different regions across Myanmar are working not only at companies like Global Cyber 8 in Yangon but also at scam centers in Shwe Kokko and in Laukkai, in the Kokang Self-Administered Zone (SAZ) in northern Shan State on the China-Myanmar border, according to former scammers interviewed by The Irrawaddy.

‘Nightmare’ of Shwe Kokko

Ko Arkar, a young man from Yangon, is one of them. He became a scammer around the end of December after being recommended by a friend working at a scam center in Shwe Kokko.

His friend had previously worked for scam centers in Laukkai and Shwe Kokko, and was called for a job interview at a scam company in Times City, one of the most luxurious shopping centers in Yangon.

Ko Arkar worked at Yilu Hong Co. Ltd. in Shwe Kokko, which offered him a monthly salary of around 1.5 million kyats.

“Initially, I planned to work for only three months and then return to Yangon. I believed that no one would find out that I worked as a scammer, though I am aware that the job would hurt my self-respect,” said Ko Arkar.

Like his colleagues, Ko Arkar looked for potential targets on social media platforms, using the fake online identity “Bella”—a fictitious Thai-Italian woman employed as the general manager of a clothing firm.

The thought that he might have ruined the lives of his targets had haunted him even in his dreams, said Ko Arkar.

“Shortly after I started working, I became tormented by feelings of guilt. I didn’t last for a week there,” Ko Arkar explained. He quit the job after four days, paying a fine of 1,000 baht to the employer.

Yilu Hong Co. Ltd. in Shwe Kokko employed around 60 people, many of them young, said Ko Arkar. He said he found many young men in their 20s working at other scam centers in Shwe Kokko, also known as Shwe Kokko Myaing.

“I felt disgusted with myself. Shwe Kokko Myaing is a nightmare to me,” he told The Irrawaddy.

“Others might not feel remorse now. But once they feel it, they will have to live with it for the rest of their lives. So, I am speaking to the media to make them aware of that,” he said.

Ko Arkar has since returned to Yangon to escape his Shwe Kokko nightmare, and is now trying to earn an honest livelihood.

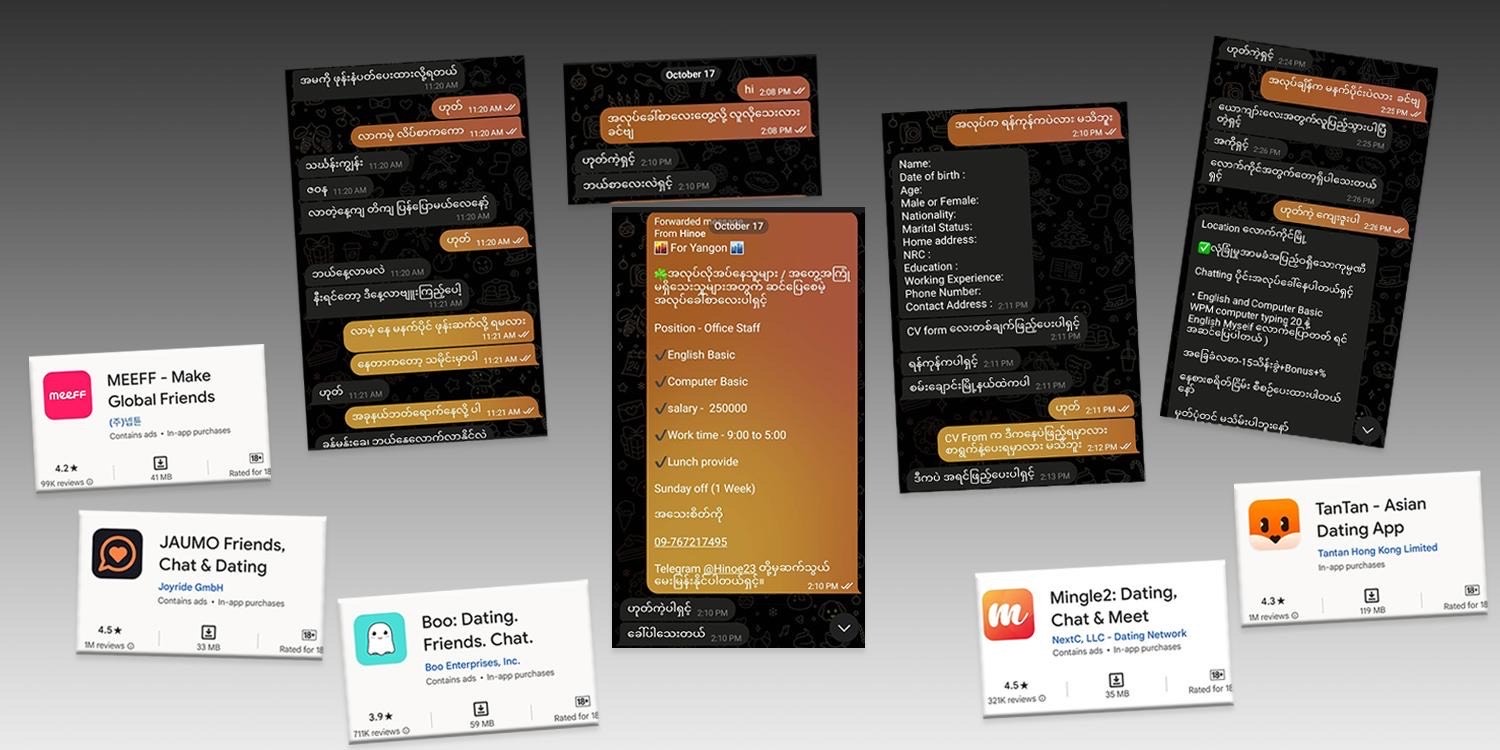

Over the past year, an increasing number of job advertisements by online syndicates based in Yangon have appeared on social media. These scam centers, such as Yilu Hong, post job openings daily on the Telegram group “Jobs in Myawaddy, Shwe Kokko.”

Global Cyber 8

Ko Oo revealed that the fake tech company, which is actually a scam center, had a workforce of around 40 people when he worked there. The center was led by a slender 28-year-old woman who, based on her appearance and poor Burmese, Ko Oo believes to be of Shan-Chinese origin.

Her photo is used as the profile picture for fake online accounts, including the one used by Ko Oo under the name Sophia. However, employees knew nothing about her, including her real name.

The company, Global Cyber 8, is situated at No. 10, Block 44 in the Nawaday Garden housing estate in Hlaing Tharyar Township, Yangon. It was registered with the Directorate of Investment and Company Administration (DICA) in July 2022, according to DICA’s official website.

The website states Global Cyber 8 is a locally owned Myanmar company that offers information services, other professional, scientific and technical services, as well as computer programming, consultancy and related services.

Before the coup, lists of directors and other basic facts about registered companies were publicly available on the DICA website. However, such information has been unavailable since the takeover.

The majority of employees at Global Cyber 8 are men who are provided accommodations at a separate house in the Nawaday Garden housing complex. The working hours are from 4 p.m. to 4 a.m., and employees are not allowed to use their phones or computers during working hours. The company supplies devices for scamming.

Employees on probation were paid 300,000 kyats a month, and were taught by their seniors about how to use chat apps, specific greetings, and conversation to lure potential victims, Ko Oo explained.

Scammers were required to collect a specific number of WhatsApp numbers daily. If they failed to meet their daily target, they were fined. However, if the victims fell for their trap and invested money in fake businesses set up by the scam syndicate, the scammers would receive a bonus, Ko Oo explained.

After completing a one-month probationary period, he decided to resign from his job when he was presented with a work contract that required a minimum commitment of three months. He did not reveal how many WhatsApp numbers he managed to collect for potential scamming during his time at Global Cyber 8.

Despite reports of forced labor, torture and fatal punishment at prison-like scam factories based at the border, there was no torture at scam syndicates based in Yangon, former employees told The Irrawaddy.

It is however believed that Yangon-based scam centers, such as Global Cyber 8 Co., are connected to scam syndicates operating at Shwe Kokko on the Thai-Myanmar border and in Laukkai on the China-Myanmar border.

This assumption was confirmed when The Irrawaddy contacted a Yangon-based scam center, posing as a job seeker responding to a job advertisement on Telegram.

The Telegram account responded that vacancies for male employees at the company in Sanchaung Township had been filled, but there were still jobs available in Laukkai.

The Irrawaddy has been monitoring the Global Cyber 8 Co compound in Nawaday Garden since October 2023. The company removed its signboard in late January 2024, but there are still some individuals residing in the compound.

DICA is responsible for suspending the registration of and dissolving companies punished for criminal activity. However, Global Cyber 8 is still listed on the DICA website, indicating that it is still in operation.

With online scam syndicates officially registered with DICA freely operating in cities like Yangon, right under the noses of the junta’s military and police, the regime’s law enforcement is becoming an object of ridicule.

The Irrawaddy made at least three calls to DICA director U Myo Min to ask about Global Cyber 8, but the calls went unanswered.

Scam syndicates thrive under military rule

More than 100,000 people engage in telecom fraud each day in at least 1,000 scam centers in Myanmar, which shares a border with southwest China, Chinese state media reported in November.

Beijing has been pressuring the regime to cooperate on cracking down on the giant, systematic scam networks that involve dozens of financiers and ringleaders of crime syndicates.

The issue has come under the international spotlight as the amount of money lost to scam syndicates operated by well-trained fraudsters has climbed into the billions of dollars.

Last year, Interpol carried out Operation Storm Makers II, a five-month investigation targeting human trafficking-based cyber fraud. Initially, cyber scam centers were mainly located in Cambodia, with human-trafficking hubs in Laos and Myanmar, but the phenomenon has spread as far as Latin America, Interpol said in its report released in December.

Scam syndicates notorious for trafficking and enslaving young job seekers from regional countries including Myanmar are considered transnational security threats.

In Myanmar alone, over the past year authorities reported rescuing trafficking victims who originated from 22 countries, largely from Karen and Shan states, Interpol reported.

Since the coup in 2021, scam syndicates have spread to the commercial capital of Yangon from their original bases in Shwe Kokko and Laukkai.

The Irrawaddy attempted to find out more about the scam centers operating in Yangon. An Irrawaddy reporter posed as a job seeker and responded to job advertisements for “finding” and “chatting” positions posted on social media.

The Irrawaddy found that there are also scam syndicates operating in condominiums and residential complexes in Sanchaung, Mingalar Taung Nyunt, Thingangyun and Kamayut townships.

One of the recruiters, whose account carried a profile picture of a woman, responded that all vacancies for male employees in Sanchaung Township had been filled, but there were job openings available in Laukkai.

Another recruiter, who used a Telegram account with a Chinese name and profile picture of a woman, responded that the office was in Thingangyun Township and that she would give the exact address only on the day of the interview.

Applicants are required to submit their CVs, and must have a basic knowledge of English and computers. Recruits are then trained to learn conversations in certain languages prepared with the help of Google Translate and people skilled in those languages.

Scam syndicates based in Yangon have dramatically scaled back their job advertising recently in response to arrests, but it is believed they are still in operation.

Is the junta deliberately ignoring scam syndicates?

Junta newspapers reported in October 2023 that the regime had sentenced a Myanmar woman to 25 years in prison for trafficking persons to a scam syndicate abroad.

Promising job opportunities with a monthly salary of almost 1.5 million kyats at a gaming center in Laos, a woman named Ma Soe Soe (aka Ma Chit Chit and Ma Mo Moe Oo) from Natmauk in Magwe Region lured six men and a woman under 22 from Naypyitaw. The job seekers were then sold to a scam syndicate, according to the report.

Since late last year, the junta has handed dozens of suspected key players from scam groups to Chinese police. However, the Myanmar Police Force did not reveal details about their identities, how and where they were arrested, or how they were defrauding people.

The regime recently raided a scam center called Supportfix in Yangon’s Tamwe Township. The scam center reportedly deceived foreigners into divulging their WhatsApp account numbers and some basic personal info, which it sold to other scam syndicates. The regime however did not reveal what punitive action it had taken against the arrested scammers. It remains unclear if any measures are being taken to arrest the accomplices.

The regime issued operating procedures for prevention and undercover investigation of online fraud on Oct. 5, 2023, with the Central Bank of Myanmar taking the lead role in anti-fraud efforts.

The Ministry of Home Affairs and Ministry of Transport and Communications will cooperate to oversee undercover investigations of telecom fraud using social media, websites and mobile applications, the regime said.

Online gambling was rampant in Hlaing Tharyar Township even before the coup in 2021, said former police officer Zarni, who worked for 24 years at the Special Intelligence Department of the Myanmar Police Force until he joined the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) after the 2021 coup. The fact that gambling and fraudulent activities continue to operate with impunity reflects corruption and deteriorating law and order, said Zarni.

With the regime weakened by the CDM and escalating armed revolt, police officers are finding it hard simply to protect themselves and do not bother to tackle corruption by lower-level police, said Zarni.

“What is happening now is higher-ups have allowed their subordinates to do anything they like as long as they don’t turn their guns on them,” said Zarni.

China issued warrants in December 2023 for the arrest of Kokang businessmen and senior members of local militias in Shan State’s Kokang SAZ including the zone’s former chairman Bai Suocheng and the then-chief of the Kokang Border Guard Force, Wei San, naming them as prime suspects in online scam operations at the border.

There were allegations that the regime attempted to protect scam bosses from Laukkai, the scam hub and capital of Kokang SAZ, despite pressure from China.

The regime has denied the allegations, but it has undeniably turned a blind eye to border guard forces and militia groups under its command operating fraud factories.

Fraud parks controlled by Bai Suocheng and Wei San in Laukkai, and the Shwe Kokko fraud park in Myawaddy controlled by Karen State Border Guard Force leader Brigadier General Saw Chit Thu, are notable examples.

Despite pressure from Beijing, the regime did little to fight telecom fraud until the Brotherhood Alliance of three ethnic armed organizations launched an anti-regime offensive known as Operation 1027 in late October 2023. The alliance cited eliminating online scam syndicates as one of the goals of its operation, and subsequently handed over Chinese citizens either overseeing scam operations or being forced to conduct scams to China. Following this, the regime arrested thousands of scammers in Laukkai and transferred them to their respective governments.

In January, the regime transferred Bai Suocheng and Wei San to Chinese authorities.

Myanmar has transferred at least 44,000 telecom scam suspects including 2,908 fugitives to China since late 2023, China’s Ministry of Public Security said in a press release on Jan. 30.

The regime announced on Feb. 9 that it had transferred a total of 50,619 individuals—48,803 from China, 1,071 from Vietnam, 537 from Thailand, 133 from Malaysia, and the rest from South Korea, Laos, Uganda, Taiwan and India—to their respective governments from Oct. 5, 2023 to Feb. 8, 2024.

The Irrawaddy is unable to report specific details about corruption behind those scam factories involving Myanmar military-affiliated militia leaders that rake in billions of US dollars annually.

It remains to be seen how the regime will investigate and take action against fraud groups that are officially registered as companies and operating in Yangon. Another question to be answered is: Where are the scammers who managed to flee Laukkai during Operation 1027 running their operations now?