6: Confronting Historical Narrative0

Chasing a legend

After crossing the long road-rail bridge over the Salween, I probably should have diverted to Motama (formerly Martaban). But I was set on driving north on Highway 8 to find the historical ruins indicated on my Periplus paper map as being near Thaton.

With two full days remaining before my flight from Yangon, I needed to reach Kinpun Village in order to go up to the Golden Rock early in the morning and be in Bago before nightfall the following day.

I skipped the Zin Kyaik Falls. In another season, what appeared on Google maps to be a tortuous narrow road up to pagodas atop the high ridge to the east would have been a tempting diversion. But on that day lowering gray clouds heralded a potential downpour.

I should have read D.G.E. Hall’s magisterial “History of Southeast Asia” more carefully. He mentions Thaton as a place called Suddhammavati, the legendary center of Mon culture, but casts doubt on the idea that the famed Mon monk Buddhaghosa brought Sinhalese Pali texts to his hometown in 403 CE, saying “no archaeological evidence exists concerning this subject.” Hall affirms as historical fact that Bagan’s King Anawrahta captured Thaton and its King Mekuta in 1057.

Where, then, were the historical ruins of Mekuta’s Mon kingdom hinted at by Periplus? Using Google translate, I asked people in Thaton. More than an hour later, as rain was falling, I found myself staring at an old gray, possibly Dvaravati-style bas-relief of the Buddha at a small rural pagoda on a muddy backroad south of the town. Slight rises in the ground nearby and a few bricks exposed beneath the roots of a tree hinted at the possibility of an old settlement.

Gold rocks

To take the classic photo of the sacred Golden Rock in the rays of a setting sun requires a good sunset and staying overnight atop the 1,000-meter-high ridge where the rock is located. Visitors are not allowed to drive up to Kyaiktiyo, and the last of the trucks that everyone must use goes up at 6 p.m. (the first departs at 6 a.m.)

With ceremonies taking place all night, Kyaiktiyo promises a cultural if not spiritual overnight experience. True pilgrims will eschew the comfort of a soft mattress at a hotel on the ridge. I was happy to enjoy the far better value offered by the Golden Sunrise Hotel near Kinpun Village below.

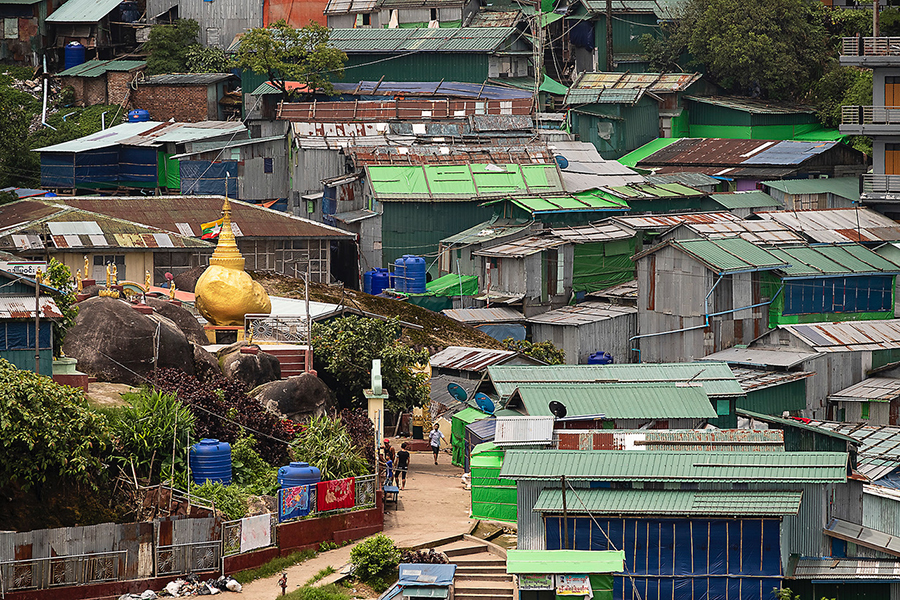

The Golden Rock is not the only gilded rock in Myanmar; not even at Kyaiktiyo, where another gold rock stands on a platform surrounded by one-floor buildings further down the ridge.

A plaque in English informs that the Golden Rock represents the position of an ascetic’s head and enshrines a Buddha hair relic and will “exist forever.” This seemingly disregards the Buddha’s teaching on insubstantiality.

The plaque also commemorates the donation of 59 viss (about 96 kg) of gold by the “multifarious national races of the Union of Myanmar” to make gold leaf and the sacred umbrella. This was hoisted in a ceremony on March 19, 2001, when Senior General Than Shwe (then chairman of the State Peace and Development Council), and Lieutenant General Khin Nyunt (then secretary 1 of the SPDC) performed a water-libation ceremony and (sic) “shared merits for their meritorious deeds with the aim of reaching state of Nibbana (Supreme Bliss).”

At the rock, most visitors make offerings and apply gold leaf before taking selfies. Away from the pagoda, down an older covered footway used by pilgrims to ascend the mount on foot, vendors sell miniature replicas of the Golden Rock and herbal remedies for evidently troubling ailments.

At the center of their displays of bottles and balms were large bowls containing a dark brown ooze. Above this, piles of blackened oily branches, vines and herbs supported the preserved head of a horned creature or a monkey at their apex. Looking like altars to some dark voodoo cult, the displays created a sense of unease. No vendor would let me photograph one. I bought a five-pack of massage balm for what I was assured was a special price, and left.

Bago in the rain

I reached Bago at the same time as a front of rain on the eastern flank of Cyclone Mora. Traffic had slowed to a crawl. There was little to be done except find a hotel.

Bago’s sights are no less impressive than those of the Mon heartland to the east, especially the majestic Shwemawdaw Pagoda, which stands like a giant in the land of phayas. Indeed, Bago, or Hanthawaddy (Pegu) as it was then known, was the capital of the Mon Kingdom (its former capital was at Martaban) for 170 years from 1369 and later became the seat of the Toungoo Dynasty.

At the Kanbawzathadi Golden Palace, old wooden pillars found at the site give a sense of the palace’s staggering scale, allaying doubt regarding the recreation’s verisimilitude. Its grandness seemed all of a piece celebrating the Toungoo Dynasty’s King Bayinnaung.

Honored as one of Myanmar’s great kings, Bayinnaung extended his 16th-century realm from Luang Prabang in the east to Manipur in the west. In 1600, 19 years after his death, Bayinnaung’s empire collapsed. By recreating his vast palace, Myanmar’s modern masters almost seemed to be inviting visitors, in Shelley’s words, to “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Driving south from Bago on the Yangon-Mandalay Highway was predictably straightforward in comparison to my route on the first day on the outward journey. The traffic in Yangon’s northern suburbs kept moving despite the rain; people were carrying on along the streets, seemingly oblivious in their wet longyis. I had many reasons to be grateful.

Oliver Hargreave created “WorldClass Drives in Myanmar” for Yomacarshare.com. The opinions expressed in this article are not those of Yomacarshare.

You may also like these stories: