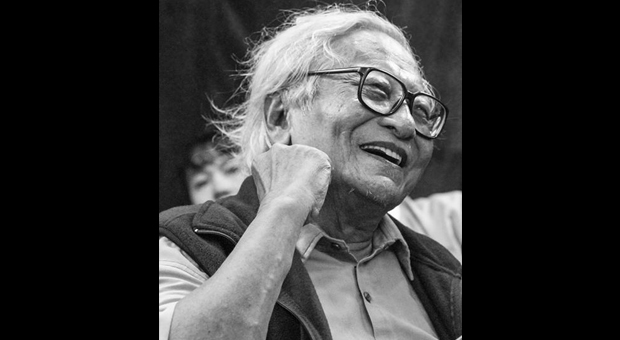

Burmese journalist Win Tin was a true believer in democracy and press freedom. He never hid his disdain for the repressive military regime and continued to challenge Burma’s current nominally civilian government.

Win Tin spent seven thousand nights in Rangoon’s notorious Insein Prison, but he had no regrets and continued to boldly carry the flag of democracy and helped keep the opposition movement alive. “The dictators can only detain our bodies, not our souls,” he once said while in prison.

The way he confronted Burma’s repressive rulers was so uncompromising and inspiring that the generals feared him, and with good reason. In Burma and beyond, many loved and respected the man who, together with Aung San Suu Kyi, has become a symbol of the country’s long struggle for democracy.

As I learned the news of his passing this morning I thought of his determination, intellectual steadfastness and the principles he upheld, and, most importantly, his contribution to the democracy movement.

Among his fellow political activists and contemporaries, Win Tin stood out as a bit different and, though it was not his intention, he outshone many other opposition figures.

One reason for this was his unbending stance and sharp reading of the political situation during the repressive regime and the current democratic transition. He remained very critical and cautious of the ongoing political reforms—a healthy and welcome approach in my view.

Win Tin was always ready to express his opinions to the media, he was eloquent and precise, and unlike many other opposition members he didn’t shy away from criticizing his party leader, Suu Kyi.

Devoted to Political Life

Win Tin was never married, but devoted his life to books, newspapers and politics. Many adored him as an example of a completely selfless man who cared about Burma’s people and showed particular concern for the younger generation.

Even when he became older and suffered from increasing health problems, he would not bother people around him with his ailments; instead he would ask them to leave him while always thanking them for their visit.

Right up until the end he was quick to offer his witty or harsh criticism of the former junta leaders, the current government, while also occasionally criticizing Suu Kyi.

Last year, he said that the National League for Democracy (NLD) leader has been too reconciliatory toward the current government. “Some of us would like to push the military into the Bay of Bengal,” he told The Washington Post, “She only wants to push them into Kandawgyi Lake,” a reference to a lake in central Rangoon.

During my first visit back to Burma in 2012, I went to meet him and asked whether it was the right decision for Suu Kyi to enter the by-elections that year and enter Parliament. He paused, looked at me with smile and said, “You know she enjoys a Hollywood star status and she is a really popular figure.”

After he was released from prison in 2008, we spoke on the phone and he outlined some of the differences between himself and Suu Kyi.

“Suu Kyi is a VIP prisoner—we spent our times in dog cells and we were treated inhumanely. Our feelings and sentiments towards the generals is not the same as Aung San Suu Kyi. She always looked at them with some understanding and she sees the military as her father’s army. But we don’t,” he said.

Despite such frank remarks, he never expressed any doubt about Suu Kyi’s leadership of the NLD and maintained she was the only political figure capable of leading Burma to democracy.

Nearly Two Decades Imprisoned

In 1989, Win Tin was a journalist when he backed Suu Kyi for the leadership of the NLD that she had formed. The same year he was thrown into prison under trumped up charges and accused of being “a communist” by the military regime that had taken power in a coup. He would spend almost two decades in prison.

I had a chance to speak with Win Tin shortly before the 1988 uprising began during a literary talk of the kind that were regularly held in a discreet manner in the old socialist Burma of former strongman Ne Win.

At a friend’s house in downtown Rangoon, some 30 writers had gathered to hear the bespectacled Win Tin speak about the increasingly tense political situation. I noticed he was outspoken but calm, and he voiced concern over the fate of Burma’s youths and students in those difficult times

Looking back, I’ve wondered if he foresaw the uprising at the time or that he would soon face decades in detention and become one of the most prominent and longest serving political prisoners in Burma.

The regime would later find out that it had been wrong to put the iron-willed Win Tin in prison. Unable to break him physically or psychologically, the generals finally gave up and ordered him released in September 2008.

He continued to oppose them even then and refused to sign a form outlining conditions that he should follow upon his release. Prison officials dragged him from his cell and dropped him at his friend’s house.

While in prison, he was often visited by foreign diplomats, US congressmen, International Red Cross officials and UN Human Rights investigators. He became one of Burma’s most well-known political prisoners and reports of his ailing health regularly appeared in the international press. Western governments, human rights organizations and press freedom groups repeatedly tried to intervene in order to free him.

Win Tin pressed on in spite of his health problems and maltreatment in prison, where he remained politically active.

In the 1990s, he asked Suu Kyi to stay the course when the regime applied a divide- and-rule strategy against the NLD in order to pressure the party into joining a military-backed national convention to draft a new constitution.

At one point, he and his prison inmates secretly compiled an 83-page human rights report and smuggled it out through a visiting UN special rapporteur. Enraged prison officials raided cells and dug up books, papers, news bulletins, two radios, and publishing materials. Win Tin and dozens of political prisoners were punished with solitary confinement in tiny “dog cells” and received extended jail sentences.

His former inmates recalled how Win Tin always encouraged them to unite and stand up against any unjust treatment imposed on them in prison.

Ironically, he also spent time with some members of the former regime who were imprisoned after Snr-Gen Than Shwe ordered a purge of Khin Nyunt’s powerful Military Intelligence (MI) units in 2004.

Several high-ranking MI officers, including one who had been in charge of Win Tin’s case, were thrown into prison and shared a cell next to his.

Win Tin also spent time in prison with the grandsons of former dictator Ne Win, who were convicted on high treason charges in the early 2000s by Than Swhe’s regime. Late last year, when they were released, one of Ne Win’s grandsons immediately went to see the old political activist.

During a funeral in Rangoon in October, former spy chief Khin Nyunt walked up to Win Tin to shake his hand. Win Tin showed no anger, but later told The Irrawaddy that the MI officers should apologize to the nation for what they had done.

Win Tin was a keen, unrelenting government critic to the very end, intent on taking down all the obstacles on Burma’s long road to democracy.

Without his guiding light, it’s hard to imagine how the democracy movement will treat the many challenges ahead during this unpredictable democratic transition, where there are still many wolves in sheeps’ clothing.