To me, Myanmar’s celebrities are viewed as role models who shape society through their actions and have a huge influence on millions of people. Their power is why the military government has been so draconian in trying to shut down this platform against them. But how strange it is that people who are famous singers and actors and lived such comfortable lives are now dying of malaria in the jungle.

On the most basic level a celebrity is someone who is: a) well known in the public sphere; and b) well liked—i.e., famous rather than infamous. Take Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Min Aung Hlaing. Both are well known, yet while Daw Aung San Suu Kyi would count as a celebrity, Min Aung Hlaing would not (no matter how many cute red outfits he wears). By this definition, there are currently no celebrities left in Myanmar. Those who are still in the public sphere have been socially boycotted, and those who have not been socially boycotted are no longer in the public sphere due to government persecution.

So I know that talking about celebrities and influencers during a coup might come across as irreverent to much more pressing socio-political issues, but I feel they are important. Indeed, my organization is based on the simple yet proven observation that Myanmar’s influencers and celebrities play leading roles as social change agents: “In Myanmar, Television personalities and celebrities are by far the most trusted source of ‘important information,’ and their insight is relied upon significantly more than religious, political, or community leaders. When asked to indicate three sources that you trust the most to learn important information, the top three responses are TV personalities, posts from my favorite Facebook pages, and community based organizations at 25%, 14%, and 9%, respectively. By contrast, political leaders of my state/region, international media, and national level political leaders were listed by 4%, 3%, and 3%, respectively.” (Taken from: “Communicating for the Future: Briefing Papers, Search for Common Ground,” November 2019).

Robert Garland, a classics professor, has argued that the phenomenon of celebrity has its origins in the ancient world, often connected to military or political glory. Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Spartacus were among the first—celebrity martyr warrior kings who rose to fame on the back of their military successes and political visions and died gloriously pursuing some noble goal. Modern celebrities, perhaps Che Guevara notwithstanding, tend to be less revolutionary. Singers, actors—their fame derives from how the public responds to the content they produce—songs or films rather than battles they’ve won.

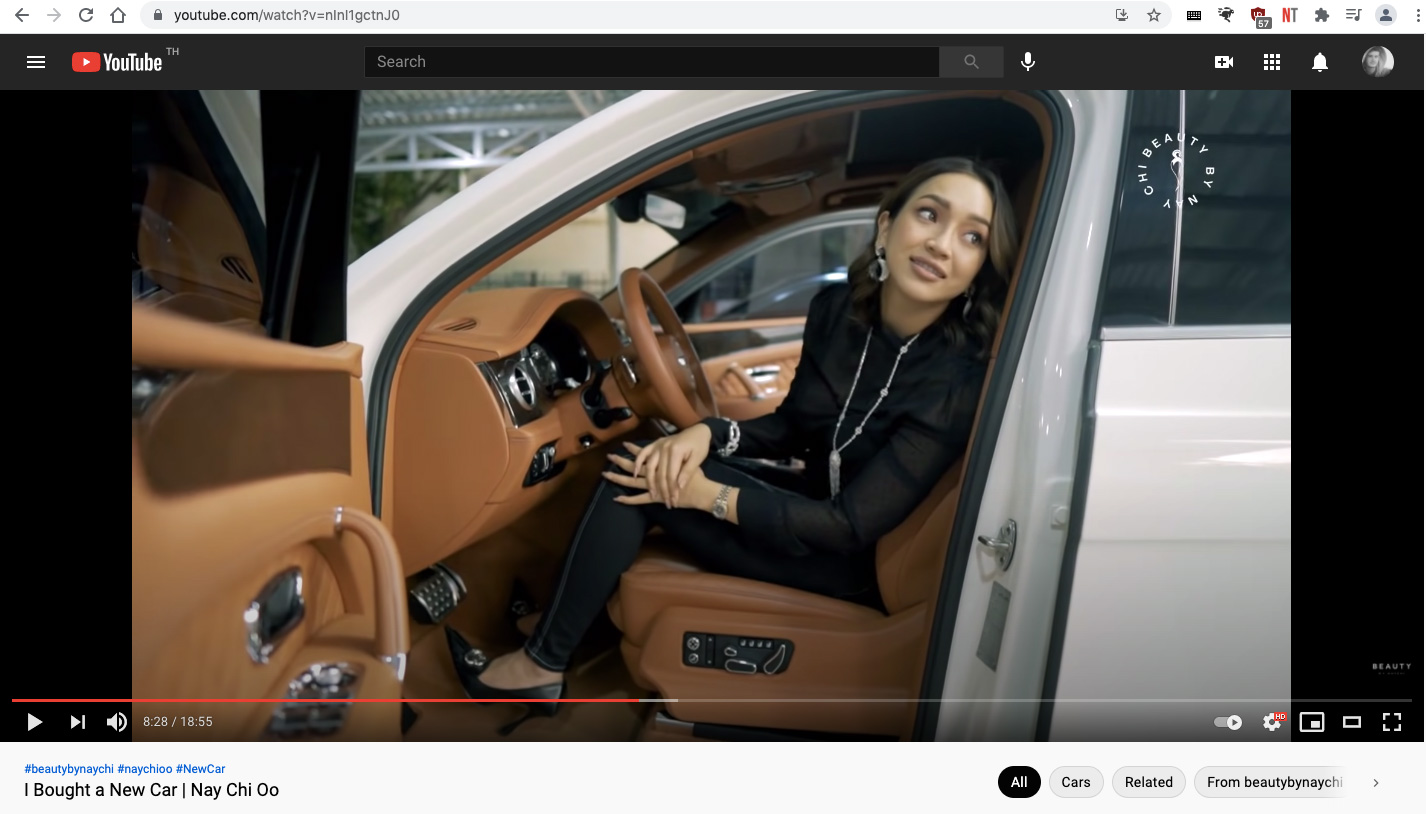

The same was true in Myanmar before the coup. As long as people liked the content, they didn’t ask too many questions. Nay Chi Oo (above) would show off watches worth tens of thousands of dollars that, quote, “Daddy bought for me” (daddy being a military official). Nay Shwe Thway Aung is the grandson of the notorious dictator Than Shwe (whom he was this close to convincing to spend US$1 billion dollars to buy Manchester United Football Club, months after 140,000 people died as the result of Cyclone Nargis, many of them as the result of the sheer incompetence of Than Shwe’s government). He has spent tens of thousands of dollars recreating Enrique Iglesias (he’s a big fan) where he literally burns genuine hundred-dollar bills. Before the coup, both had hundreds of thousands of fans; they were bona fide celebrities.

After the coup, the public has become far more discerning. Nay Chi Oo stayed ominously silent for the first few weeks after the coup, only responding after her fans requested her to do so. When she did join the protests, it was with an entourage of bodyguards. She was destroyed on social media, completely derided. Subsequent attempts to show that she was “with the people”, likewise, did not go down well. She tried to donate to a Civil Disobedience Movement charity, and the donation was refunded to her, with the organization saying they didn’t want her money. There was a feeling that she and others were protesting not because they believed in the cause, but because social media expediency dictated that she must. Staying silent has become social (media) suicide.

Hers is one of the most high-profile cases of social media boycotting, where social media users dole out social media punishment on those who they feel deserve it.

Interestingly, now even celebrities that do not have military backgrounds are not immune from social punishment. Those who are deemed by the public to not be speaking up enough face social shaming and boycotting. Some of the biggest celebrities in Myanmar, with millions of fans, are being boycotted for their silence in the face of the coup. Sai Sai lost 19,000 on the first day of the coup, with a netizen telling Frontier magazine that celebrities are “the parasites of society. They’ll do anything to avoid a normal life. They just want to live in a silver platter with minimum effort.”

If there are exonerating circumstances for those who have been boycotted, it’s the fact that the military government is actively hunting down celebrities that speak out. Using a law known as 505, (written in 1861, by the way), which pertains to “Statements conducing to public mischief”. Section 505(b), notably, penalizes making, publishing or circulating “any statement, rumor or report, with intent to cause, or which is likely to cause, fear or alarm to the public or to any section of the public whereby any person may be induced to commit an offense against the State or against the public tranquility”.

State TV publishes daily lists of arrest warrants issued for celebrities and public figures whom they have deemed to have violated 505. Several high-profile celebs have been arrested at their houses in the middle of the night, and are now in prison. Many more are now in hiding around the country. A handful have escaped, though with the government requiring that airlines submit names of those on flights 10 days before flights, and arrests at the airport a real threat, the scope for more leaving the country is both very limited and very risky.

When I flew out of Yangon in May, I randomly met an old celebrity friend at the airport. He was only able to escape because the government had put his/her music group on the 505 list rather than his individual name (newsflash: the government is stupid). At the airport he/she was bricking it for fear of being arrested. While he/she made the flight safely, tighter restrictions put in place the next day mean that the other members of the group will likely not be able to join them.

The 505 law then has undeniably made people think twice about speaking out. Though interestingly it has become somewhat of a badge of honor—a sign that an individual is resisting the government.

The main source of celebrity income is brand endorsement, though it is a criminal offense to work with any celebrity who is on the 505 list (and even then, these individuals are currently in hiding). Working with anyone who is not on the list is equally unviable. Though depressingly probably more for reasons of economic expediency rather than noble ideology, brands have been quick to cancel brand ambassadorships and distance themselves from anyone who has been socially boycotted, most probably because the brands run the risk of being boycotted themselves. While utterly unimportant given the circumstances, from a commercial brand perspective there are no longer any celebrities in Myanmar. Either they are in hiding and therefore unable to do anything publicly, or they have been completely discredited. Social boycotting and shaming is a powerful force.

The interesting thing here is that the punishment of social boycotting is administered through a form of social media mob justice rather than any centralized judicial system. Different celebrities are on different lists. These lists are compiled by individuals based on whatever research they choose or do not choose to do. If the list is popular enough, it becomes canon. There are no appeals.

It’s possible to argue that celebrities then are in a difficult position. If they speak out, they are putting themselves, their families and their assets at serious risk, and most probably would have to go into hiding or on the run in the jungle. If they keep silent on the issue, they are safe, but become pariahs—inverted celebrities. Whereas before they were adored by millions, now they will be despised by them. There is no real middle ground.

If a normal person, a non-celebrity, stays neutral, people might find it disappointing, but unless they are vocally supporting the coup nobody will really care. For celebrities, however, that is not the case. The difference is that celebrities, by virtue of being celebrities, have a public platform, which they owe to their fans. And in not using their platform to speak out, their fans feel betrayed. In a sense, this is unfair. Celebrities did not sign up to this, and are unable to opt out.

Obviously neither option is ideal. The extent to which a celebrity can be blamed for putting themselves first is open to debate. None of the celebrities who have been socially boycotted played any role in organizing the coup, and if asked in private, many would strongly condemn it (indeed many of those who have been boycotted were part of the early protests).

However, the fact is that celebrities in Myanmar, and around the world, have a huge platform to influence public opinion. A celebrity is actually much more than someone who has xxx,xxx followers or likes; they are role models who shape society through their actions (or inactions) and have a huge influence on millions of people. This platform, this power is why the military government has been so draconian in making sure this platform is not used against them. Ultimately, not using their platform to speak out is not a crime, and these individuals have every right to keep their heads down, to prioritize their safety. However, their fans also have every right to disavow them for not taking a stand.

Raymond, one of Myanmar’s most famous rock stars, tragically died some weeks ago from malaria. He had been hiding in the jungle in an ethnic controlled area in order to evade arrest, after a 505 arrest warrant was issued by the military junta. Despite the danger, he continued to “conduct public mischief”, using his platform to post regularly about the coup on his Facebook account. A former Miss Myanmar has taken up arms, doing military training in the jungle. Two of Myanmar’s most famous actors were arrested at their homes and have been in prison for the past three months. These are not the actions of people who are worried they might lose fans; these are the actions of people doing what they believe is right, regardless of the risks. In light of these actions, inaction just seems that little bit less palatable. What would Spartacus do?

An argument can be made for a new generation of celebrities since the coup which are much more in line with the original celebrities of antiquity. Politicians such as Dr Sasa, (who now has 2.5 million Facebook followers) and journalists such as Mratt Kyaw Thu (with 200,000+ subscribers on his telegram channel) are part of a new political revolutionary group of famous people. While I think both would much prefer to be known as politicians and journalists respectively, and I highly doubt they would ever engage in the kind of brand endorsements that normally characterizes the modern celebrity, their fame is undeniable. That the public eye in Myanmar is increasingly turning to people like this who are using fame (albeit from outside the country and the public sphere) for a good cause rather than an end in itself can only be a good thing. These are more noble celebrities with more integrity, more to say, and the more attention they get, the better. Many thanks to Nay for helping to develop this idea.

Charlie Artingstoll moved to Yangon, where he worked for NGOs for a number of years. Now, he works with celebrities and influencers in social media campaigns that communicate socially beneficial messages. He has also written on Microfinance and the Ultra-poor, the War on Drugs , Suu Kyi and Islamophobia, the hip hop scene in Myanmar, and most recently about mental health in the country.

You may also like these stories:

Xi Says China Doesn’t Bully Other Countries: Myanmar’s People Know Better

Tabayin Villagers Cannot Count Dead Amid Myanmar Junta Attacks

Myanmar Junta Suspends Trials Inside Insein Prison Due to COVID-19