July 2018 marked 71 years since General Aung San was assassinated. During these years, we had the AFPFL government, the caretaker government, U Nu’s Pyi Daung Su government, the revolutionary government, etc. All together, there were eight governments. All these governments performed homage-paying ceremonies at the Martyr’s Mausoleum every year on July 19. It is however apparent that paying homage every year does not necessarily mean following the principles and programs of the national leader. The proof of this is that Myanmar, despite being one of the first countries in the region to attain independence, and in spite of its rich resources, presently belongs to the group of least developed countries in ASEAN, and in the world in general. This statement requires a review of the principles and the programs advocated by Gen. Aung San during his lifetime. These can be summarized as follows:

- During his university days, he tried to gain knowledge of politics and the requirements of the country.

- After leaving university, he joined the Do-Bama-Asiyone, the political organization fighting for the country’s freedom, and was fully engaged in the cause of the country.

- When World War II broke out, he risked his life and went abroad to form the Burma Independence Army (BIA).

- After the war, as the chief of the interim government, his priorities were: (1) national unity; and (2) national development.

After 71 years, we find our country’s main requirements are the same two as existed in the time of Gen. Aung San. Regarding the task of national unity, the representatives of the defense forces as well as of the elected bodies of the government are ostensibly negotiating to achieve peace and tranquility for the country.

Regarding development, U Aung San, during a short period of around eight months as the chief of the cabinet, initiated a development plan for the country with the objective of terminating the colonial economy and encouraging the development of the industrial sector. In 1945, Governor Reginald Dorman-Smith came back to Yangon with the “Blueprint for Burma” he and his exiled government had worked out in Simla during the war. This plan was to carry on with the 1935 Burma Constitution while separating the five states of Shan, Kayin, Kayah, Kachin and Chin from the Union. The people of the country and the AFPFL rejected Dorman-Smith’s “White Paper Plan”. In September 1946, following the change in British government that brought Clement Attlee to power, the new governor, Hubert Rance, arrived and Bogyoke Aung San became the head of the cabinet. In this short period, the country saw the launch of its most important plan, the “Sorrento Villa Plan”, also known as the “Economic Development for Burma” plan. (Sorrento Villa is the building at the corner of Pyi Road and Hanthawaddy roundabout, presently known as the Sar-Pe-Baik Hman Building.)

Bogyoke Aung San and later democratic governments understood the significance of the country’s long-term development plans and the requirement to develop the industrial sector of the country. This policy was adopted by U Nu’s AFPFL government, which applied measures to develop the industrial sector, and adopted a policy of export orientation and import substitution. Under this policy, the country exported textiles and processed foodstuffs starting from 1953 — the first time in history that Myanmar exported industrial products.

In recent years, we have had politicians who say publicly that Yangon shall reach the standard of Singapore in 10 years, or that Myanmar shall overtake Singapore in 20 years. It is astonishing how some responsible persons can make such statements without any basis. In the first place, we have 14 states and divisions and over 400 towns; any sensible person would ask, “Is it fair and justified to have only Yangon be highly developed, from the standpoint of national unity?” Additionally, there are several technical issues such as: In Yangon, only 30 percent of households receive water supplied from the YCDC; only 60 percent of households have electric meter boxes; around 50 percent of the areas in Yangon suffer from floods whenever there are heavy rains, and so on. It would take more than 10 years just to overcome these basic challenges. Yangon and Singapore have similar populations, of about 5.5 million. In terms of area, Yangon is over 300 sq. miles while Singapore is slightly smaller. Singapore has about 600,000 vehicles and Yangon about half that, and yet, in peak hours, it takes about three hours to drive from the western suburb of Hlaing Thaya to Sule Pagoda in the heart of Yangon’s CBD.

Just to provide some sense of the time needed to develop city infrastructure, Singapore started with the construction of the MRT (Mass Rapid Transport) system in 1987. After 26 years, in 2013, only 40 percent, or 83 km, of the line was complete. At that time it was used daily by 1 million people. The whole 200 km was completed in 2016 and it now has 3.1 million passengers daily.

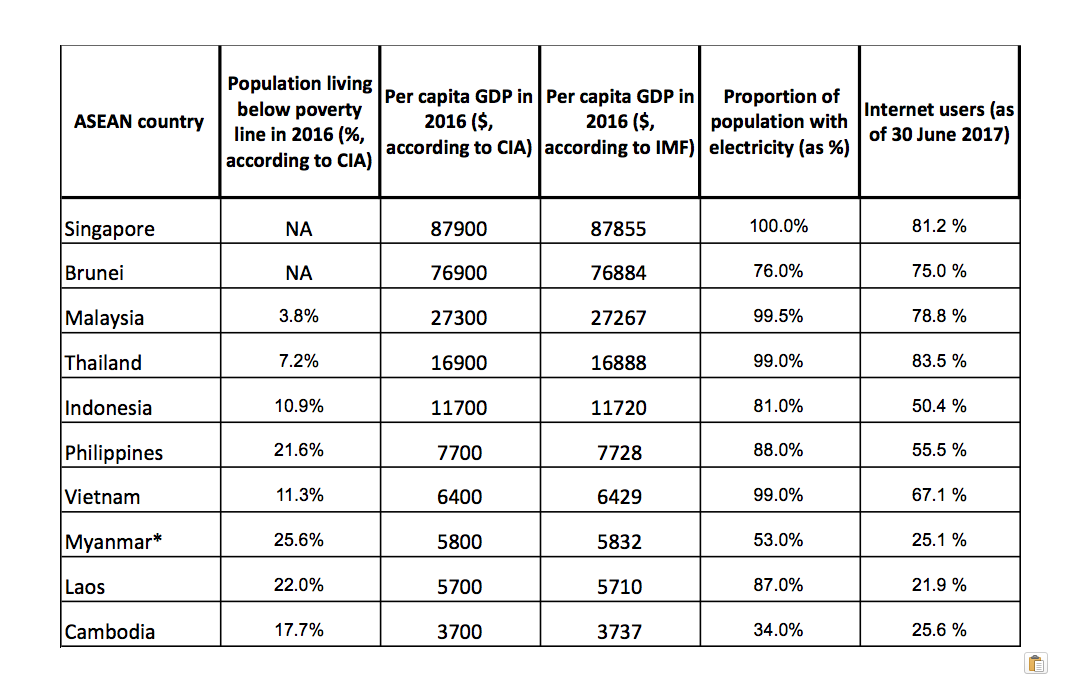

Regarding the statement on Myanmar overtaking Singapore in 20 years, Myanmar is a country of 2,612,200 sq. miles, while Singapore’s area is 277 sq. miles — slightly smaller than Yangon’s. Myanmar has a population of over 50 million and Singapore just over 5.5 million; the per capita GDP of Myanmar is around USD5,800, whereas Singapore’s per capita GDP is more than 15 times higher at USD87,900. Their circumstances and development levels are vastly dissimilar. Among ASEAN nations, more appropriate comparisons would be with Vietnam (per capita GDP USD6,400) or Laos (per capita GDP USD5,700). However, a much larger percentage of the population has electricity in Laos than in Myanmar. Even our immediate neighbor Thailand’s per capita GDP of USD17,000 is three times that of Myanmar’s. The attached table compares ASEAN nations’ development indicators. Per capita GDP is the most important figure for this purpose. However, the percentage of the population living below the national poverty line and percentage of households with electricity are also closely related to the countries’ general development.

In general, statements on the country’s progress, like when and how the country’s GDP shall increase, issues on the industrial sector, on electrification, communication, unemployment, etc., should only be made based on scientific facts. Only the country’s long- and short-term plans can provide reliable and convincing information. Bogyoke Aung San started the country’s development plan during his eight months in office as the head of the cabinet. It is time for us to launch a comprehensive development plan — a requisite for a country that has suffered five decades without parliamentary democracy.

Water supply, drainage, roads, electricity, etc. are material and physical issues that can be solved within a few decades if there is money available, if we have Devas to help us with billions of dollars. Foreign companies can construct for us the underground trains, Yangon’s floods can be eradicated with underground drains and sluice gates, and so on. However, our problem is that we do not even have qualified engineers and technicians to maintain these modern systems. The main issue facing our country is “comprehensive development” — the education, morals and attitudes of our people towards society and the environment.

Every day we observe our people trying to get into buses without queuing, with no consideration for pregnant women, the elderly or the handicapped. Many drivers have no respect for the traffic rules; many of us chew beetlenut and have the habit of spitting, etc. Garbage being thrown out of very expensive cars straight onto the streets is a common sight; we can therefore conclude that material wealth cannot be equated with high cultural and educational standards. The citizens of Myanmar by tradition are polite and cultured people, but five decades under dictatorship, and living with the injustice and inequality, the corruption, the deprivation of such basic rights as the right to work and the right to education, etc., have created an attitude in many of our people of self-preservation: get oneself into the bus and get oneself moving as quickly as possible. This is reflected in our environment every day. It is time we started re-educating our people about our old traditions — to respect the elderly, to give preference to the weak and the handicapped — to begin a re-education process of “the way we were”.

In summary, programs on education, civics and behavior-improvement should also be an integral part of the nation’s development plans. We should begin with such programs because education is the most important asset we can possess, and such programs are less costly than building new cities.

Dr. Kyaw Lat is an architect and urban planner who has worked with the Department of Human Settlements and Housing Development, Ministry of Construction and the United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (Habitat). He was also a professor at Yangon and Mandalay Technological universities, professor at Cologne University of Applied Sciences, Germany, and finally before his retirement an advisor to the Yangon City and Development Committee from 2011 until 2016.