Holding the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) meeting in Myanmar, and the Chinese foreign minister’s decision to visit the war-torn country early this month in order to co-host it, conveyed some crucial messages that China is seeking to reassert ties with Mekong countries through Myanmar.

In Myanmar, where Beijing’s strategic and economic interests abound, China has three ambitious plans to be carefully watched following Wang’s trip.

China may be considering beginning its ambitious projects in areas where there is less risk in Myanmar. These ambitious plans seek not only to dramatically boost China’s economic and political clout in Myanmar but also to give geopolitical advantages to China and its allied ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in the eastern and northern parts of Shan State.

With Western players shunning Myanmar due to the regime’s human rights abuses, China could become the sole player in infrastructure projects in the country, helping to line the regime’s pockets. Observers said new international land-sea trade corridors under the LMC will make Myanmar over-reliant on China economically and, as a result, it is inevitable that it will become a client state of China.

LMC projects

Born of China’s unilateral dam construction, the LMC is a sub-regional cooperation mechanism consisting of the six countries through which the Mekong River flows: China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. Since 2016, China has emerged as an active player and guarantor for Mekong countries ranging from cultural events and agriculture projects to regional connectivity infrastructure projects.

During the meeting in Myanmar, China proposed six cooperative programs involving agriculture, water resources, digital economy, aerospace, education and public health.

However, the LMC’s main agenda is to tout transport infrastructure projects and cross-border economic cooperation among the countries, e.g., the construction of the China-Laos Railway.

Last year in August, China announced it would transfer over USD$6 million to the Myanmar military regime to fund 21 projects under the LMC, including providing financial support for culture, agriculture, science, tourism, animal vaccines, and others.

During his meeting with the regime’s foreign minister Wunna Maung Lwin, Wang said Beijing is willing to strengthen coordination and cooperation with Myanmar “to promote the quality of and upgrade the LMC.” Moreover, the China-funded Mekong-Lancang Cooperation National Coordination Unit (Myanmar) has opened in the country.

A local observer on China-Myanmar relations said Wang’s trip showed that Beijing has given full support to the regime via the LMC, though some Chinese analysts deny this. The regime is seriously in need of foreign investment to ease the political and social crises sparked by the coup.

“If the country totally falls into anarchy, it would be a nightmare for China. They do not want to see that [for their own interests],” she said.

Under the LMC, China is actively supporting Myanmar in different sectors, including a lesser-known strategic port project in the eastern part of Shan State.

Early last month, the Chinese Embassy announced that a feasibility study (FS) for the Wan Pong Port upgrade project had been completed with the support of the LMC Special Fund. Since 2018, China has injected millions of dollars to transform the port into a regional trade hub. According to the Chinese Embassy, the FS includes environmental and social impact assessments, cost estimates, design plans and operations training programs.

Located in Tachileik District in the eastern part of Shan State, the strategic port lies on the Mekong River. It is a important project for China as it will allow it to expand its influence over the Mekong region. Beijing is committed to turning Wan Pong into one of the major regional ports on the Mekong.

The port plays a major role in trade with Laos and will also open the door to connecting with other Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) countries. Moreover, during the pandemic, Myanmar exported rice to China through the port via Laos.

The completion of the expansion project will allow Wan Pong Port to handle shipping containers, which will help to boost trade between Myanmar and GMS countries.

The plan will also enhance China’s economic influence in the eastern part of Shan State. After the military takeover in Myanmar, China appeared to make an assertive effort to gain control of the eastern part of the Salween River, including the east part of Shan State.

Furthermore, under the LMC, the resumption of hydropower plants on the Salween River and the incorporation of so-called development projects of the Salween basin into the Greater Mekong Project is one of the main priorities for China.

China plans to build at least seven dams along the Salween River, including mega dams in Shan State. Planned as a joint development by Chinese and Thai companies, the 7,000-megawatt Mong Tan Dam, known locally as the Tasang Dam in Shan State, will be the largest hydropower dam in the country. Despite strong opposition from locals, the dam is in the planning stage.

The move will increase China’s economic and political clout and give economic and geopolitical advantages to China and its allied EAOs in the area, including the United Wa State Army (UWSA).

Since the military takeover, China has stepped up its efforts to create a buffer zone along the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) and along the eastern Salween River with the help of its allies among the EAOs. Given the conflict dynamic between its allied EAOs and the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS), China appears to be urging friendly EAOs to take secure territorial control in those areas.

More importantly, China’s rising influence in the Salween basin could yield the resumption of hydropower plants along the Salween River and the incorporation of other development projects in the Salween basin under the LMC.

New international land-sea trade corridors

China’s expansion of the transportation corridors under the LMC is another major issue that needs to be carefully watched.

Given Myanmar’s unique geographical position in China’s grand infrastructure plan, the war-torn country is crucial for China to access South Asia and Southeast Asia via the Indian Ocean. Chinese media often tout the China-Laos Railway as a new engine to boost economic cooperation between China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) under the LMC and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

In April, China launched a land-sea trade corridor that opened direct access to the Indian Ocean via Myanmar. The new trade corridor travels through four Mekong countries—China (Chongqing), Laos (Vientiane), Thailand (Bangkok) and Myanmar (Yangon)—to the Indian Ocean, according to Chinese media.

The route has received less attention as many have confused it with the land-sea route from Sichuan to Singapore via Myanmar, which saw its first test run in August 2021.

While Myanmar is seeing an increasing number of armed conflicts across the country, China officially inaugurated a new land-sea trade route: Chongqing-Lancang-Chinshwehaw-Mandalay- Yangon-Singapore, the last leg via the Indian Ocean.

The route goes from Chongqing in China’s Sichuan province to Lancang in China’s Yunnan province, Chinshwehaw in the Kokang Self-Administered Zone in northern Shan State, and Yangon, the commercial capital, and then to Singapore via the Indian Ocean.

Goods will be transported by rail from China’s Chongqing to Lancang and later transferred by road from Myanmar’s Chinshwehaw to Yangon and shipped from Yangon port to Singapore.

The Chinese Embassy said that the new route is “an important breakthrough in strengthening China-Myanmar trade relations for Beijing.” The route cuts transport time in half. Goods from inland areas in western China can go directly to Southeast Asia and South Asia through Myanmar in a short time.

The new route is expected to strengthen Chongqing’s connectivity with ASEAN and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) members. Given the current situation in Myanmar, the route will have geopolitical and economic advantages for China.

Many may wonder how the new route can succeed, as it passes through areas where many armed conflicts occur. Along the new land-sea corridor in Myanmar, particularly in northern Shan State, EAOs with close ties to China control the ground after successfully driving the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) out of strategic positions in the area. EAOs with close ties to China fully managed to guard the route in northern Shan State.

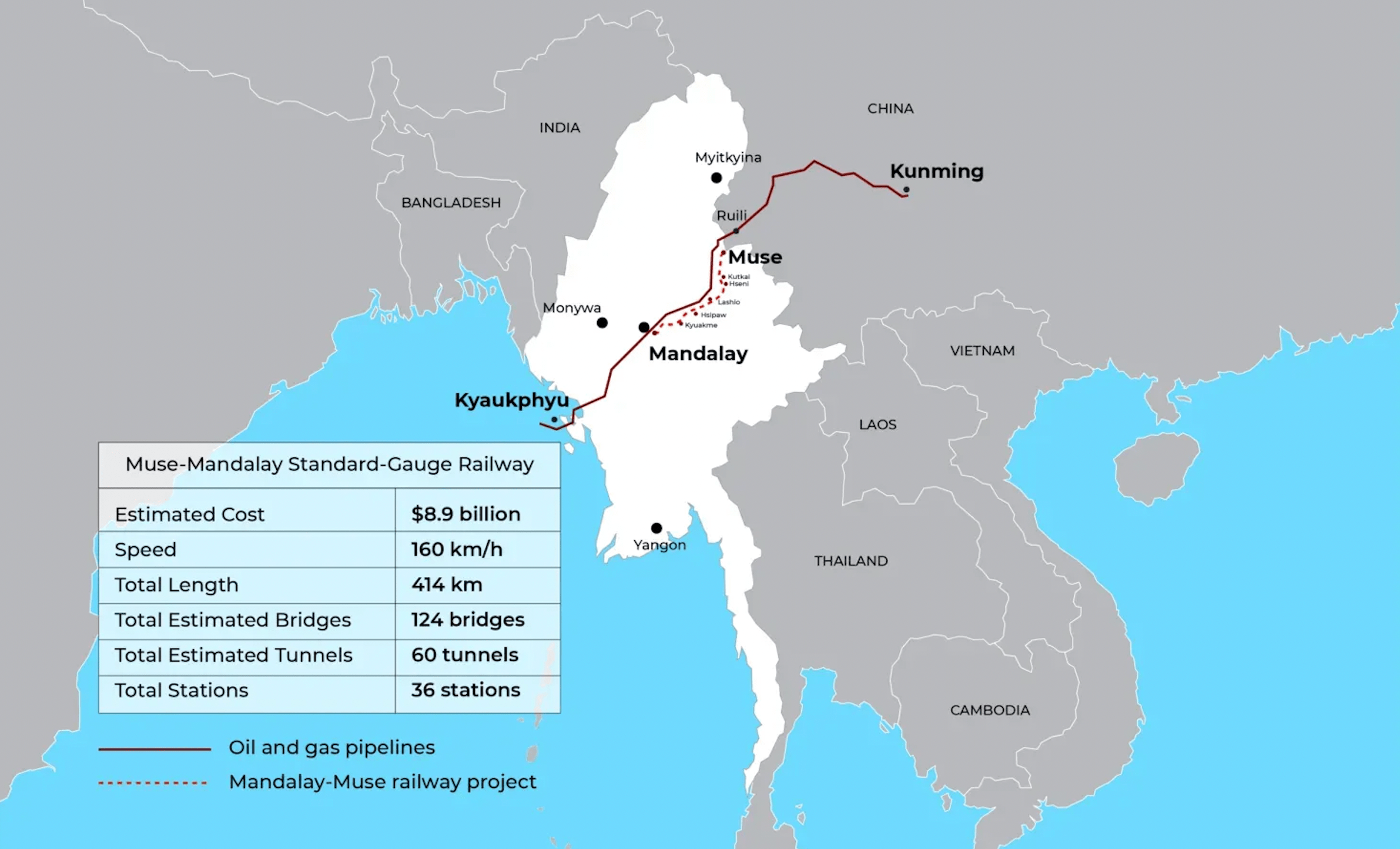

Moreover, China’s international trade corridors aren’t complete without the China-Myanmar Railway. Recently, China completed construction of the Dali-Ruili Railway, which is a crucial part of the China-Myanmar International trade route. The Chinese Embassy said that the new railway would open this year. The railway was initially planned to connect with the China-Myanmar Railway, an important part of Beijing’s strategic plan to create access to the Indian Ocean for landlocked Yunnan.

The railway is planned to link with the Muse-Mandalay railway, a part of the China-Myanmar Railway. The long-awaited USD$9-billion project faced several reviews under the National League for Democracy government.

To complete its regional logistics connectivity, constructing the Muse-Mandalay Railway is vital for China. In late June, Chinese media and regime-controlled media revealed that China and the regime’s governing body, the State Administration Council (SAC), are in negotiations to begin constructing the Muse-Mandalay Railway project. Following Wang’s trip, a question has arisen about whether China has stepped up activities to get the project off the ground.

China-Myanmar Economic Corridor and CMEC Plus

Since the coup, China has been cautious about the instability in Myanmar and anti-China sentiment, despite keeping the CMEC on track with ongoing discussions and preparations with the SAC. However, in August last year, China officially called the SAC a “government” and resumed publicly talking about the CMEC.

The SAC also reviewed a total of 97 China-backed projects and urged China to resume development and infrastructure projects, particularly the Kyaukphyu SEZ (KPSEZ) in Rakhine. It also said China is committed to supporting 200 million yuan (about $30 million) worth of development projects in Rakhine, including the CMEC. The SAC also held the first-ever ministerial-level meeting on CMEC projects in January, attended by ministers from Mandalay, Rakhine, Yangon, Shan, Ayeyarwady and Magwe.

When carefully analyzing this month’s discussion between Wang and U Wunna Maung Lwin, it is clear that China is taking the pulse of negative sentiment among Myanmar people.

Reviving projects under China’s ambitious BRI is one of the top priorities for China in the post-pandemic period in the Mekong region. Beijing has already made several preparations to implement CMEC projects during the last year, despite Myanmar being in turmoil following the military takeover.

During Wang’s trip, China showed a willingness to resume ambitious projects under the CMEC, including the KPSEZ and cross-border interconnection projects. The KPSEZ is a major infrastructure project under the BRI and has made some progress since the coup, including inviting bids to provide legal services to the project and signing an agreement with a Myanmar consulting company, MSR, to conduct an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA).

Beijing also hinted that it has a plan to turn CMEC into “CMEC Plus,” which means China will invite LMC members to cooperate on it. The statement also revealed that China and Myanmar agreed to expedite construction of cross-border interconnection projects in which Myanmar will buy electricity from China. Under the NLD government, an agreement to study the projects was signed with China Southern Power Grid (CSG), a Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE).

China has a plan to connect the grid via two routes in Myanmar. The first route is from Dhong Dai in Yunnan province, China, to Muse and Hopong in northern Shan State, Loikaw in Kayah State, and Phayakyi in Bago Region. Another route is from Yunnan to Kachin’s Bhamo and Ohntaw in Sagaing Region, with a plan to later connect with Myanmar’s national gird.

In May, before the Mekong summit, Chinese Ambassador to Myanmar Chen Hai and regime Minister for Electricity U Thaung Han met in Naypyitaw, the capital of Myanmar. According to a statement, the two sides discussed implementing cross-border interconnection and hydropower projects in the country.

Analysts have already warned that there is a dependency risk when relying on foreign sources, especially China. As the infrastructure of power grids will need to pass through high conflict areas, further militarization of these areas is possible.

They said China fully understands that the country may be falling into anarchy. So, it has taken further steps to expand the buffer zone in ethnic areas and also engaged in activities that indirectly support the regime.

“The regime has to bear the growing influence of China on Naypyitaw and ethnic areas. Moreover, it also has to bear the growing influence of China-backed armed groups in the country,” one observer said.

The majority of strategic projects planned under the CMEC are in ethnic areas where armed conflicts occur frequently. However, northern Shan State, where most of the strategic CMEC projects will be built, is dominated by ethnic armed groups with close ties to China. So the risk to China there is lower.

China may soon launch practical implementation of BRI projects, concentrating first on areas where there is less risk. These could be areas dominated by ethnic armed groups with good relationships or close ties with China.

You may also like these stories:

Top China Official Reaffirms Beijing’s Support for Myanmar Junta

Myanmar Junta Airstrikes Continue in Kayah State

Hell Hounds Are Loose in Myanmar; Who Can Stop Them?