Myanmar military commander-in-chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing has seriously lost face over the past month or more, as his armed forces have suffered dramatic setbacks on the battlefield in northern Shan State and beyond. The defeats inflicted on it by rebel groups in the north and elsewhere present the Myanmar junta with the biggest challenge to its rule since the coup in February 2021.

The regime has lost hundreds of outposts, towns and trade routes in the coordinated offensive, which was launched across northern Shan State, Kachin State and upper Sagaing Region in late October.

Operation 1027 has proven to be a game changer, as some analysts have dubbed it. But will it also turn out to be a regime changer, or will China and neighbors including India try to preserve the junta’s grip on power?

The Myanmar regime has approached its giant northern neighbor China, asking it to intervene in the domestic conflict. Will China assist the regime in the current conflict? Can either side trust it?

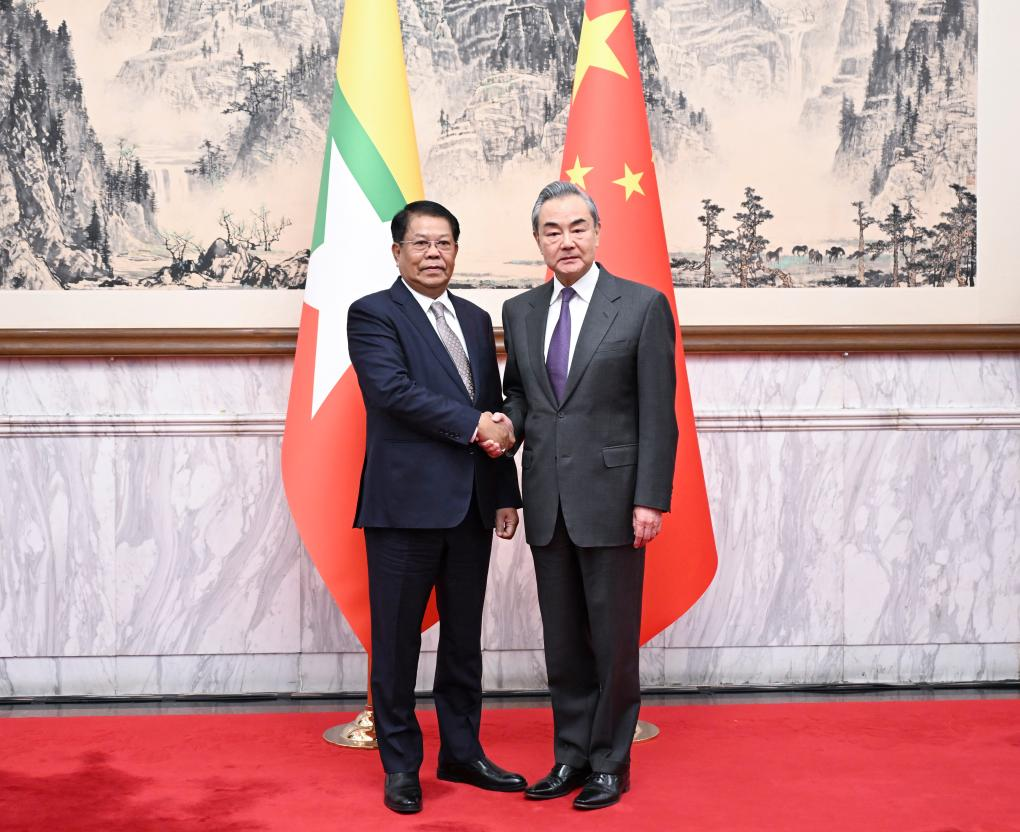

This week, as the allied ethnic forces advanced on Laukkai—a city in the Kokang area of northern Shan State where both regime forces and junta-allied Border Guard Forces are based—Myanmar’s Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Than Swe flew to Beijing and held talks with China’s top diplomat Wang Yi.

China hopes for ‘national reconciliation’

“Myanmar still faces many domestic challenges and hopes to continue to receive support and help from China to achieve domestic peace and stability,” Than Swe told Wang, according to a Chinese Foreign Ministry statement.

Reading between the lines of his message, it’s apparent that the Myanmar regime is desperate to stop the war in the north and is asking for China’s help in bringing this about.

In reply, Wang, who is no stranger to Myanmar politics and met with Aung San Suu Kyi weeks before the coup in 2021, said China would not interfere in Myanmar’s internal affairs, but hoped the country could “achieve national reconciliation” and “continue its political transformation process under the constitutional framework as soon as possible”.

It is believed the Myanmar side asked China to exercise its influence to persuade the Brotherhood Alliance of three ethnic armed organizations (EAOs)—the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) and the Arakan Army (AA)—to stop fighting and enter a dialogue. The junta likely hopes, with help from Beijing, to isolate the ethnic armed groups. However, having met with success so far in their efforts to drive the regime out of northern Shan State, will the insurgent forces listen to China?

Indeed, as in the past, the junta needs China’s help to act as a mediator if it is to broker a truce with the ethnic armed alliance. This time it needs to do so in order to sustain its regime, and everyone knows that China has considerable influence over the ethnic forces based in northern Shan State. Some cynics have even joked that these forces are “little armies of the PLA”, referring to China’s People’s Liberation Army.

In any case, while the Myanmar regime seeks its strategic support, China is likely to maintain its “principle of non-interference” in the current conflict.

Chinese special envoy Deng Xijun recently traveled to the China-Myanmar border and held meetings with several leaders of key ethnic forces including the MNDAA, TNLA and AA. He also held a separate meeting with representatives of the Kachin Independence Army. Ethnic leaders sensed that China is concerned about the growing instability on the border and worried that if the regime cannot control Myanmar, who will?

China’s southwestern province of Yunnan shares a 2,000-km border with Myanmar’s Shan and Kachin states.

As Than Swe met with Wang in Beijing, regime-controlled media reported that Myanmar and China discussed accelerating construction of the Kyaukphyu deep-seaport in western Myanmar’s Rakhine State and a railroad linking Rakhine with Yunnan Province via Mandalay, the second-largest city in Myanmar. Analysts say the Myanmar junta plans to speed up the railroad project soon to please China, in a quid pro quo.

Does Min Aung Hlaing eye a political solution?

On Monday, during a regime cabinet meeting, Min Aung Hlaing said, “If armed groups persevere in their errors only local people will suffer the impacts [of the fighting],” before urging the EAOs to seek political solutions to problems.

Min Aung Hlaing, however, has warned that the Myanmar military would not accept any action that threatened to result in the breakup of the Union or harm the “three main national causes”, referring to the military’s three-part political ideology: non-disintegration of the union; non-disintegration of national solidarity; and perpetuation of sovereignty—something the Myanmar military believes it has primary responsibility for upholding.

It is only the ethnic regions and their residents that will suffer the consequences if the “three main national causes” are harmed, Min Aung Hlaing threatened. Tough words.

His comments raise the question: If Myanmar descends further into disintegration, will the junta resort to extreme measures?

But underneath this belligerent talk, Min Aung Hlaing faces internal opposition from his top generals and officers who are frustrated by the heavy military setbacks and public humiliation. Unquestionably, Myanmar people seem to be happier these days, watching the military suffer heavy casualties.

Navy ships and live-fire drills

China remains the Myanmar junta’s key supporter and arms supplier.

In the last week of November, as the Myanmar regime continued to lose soldiers, including officers, on the battlefield, three Chinese navy ships arrived in Myanmar for joint drills with the Myanmar navy, to show that Myanmar remained an important ally.

In the same week, the Chinese military began live-fire drills across the border from northern Shan State, beefing up security as violence escalated between the junta and armed rebel groups.

The “real combat training” on the Chinese side of the border aimed to test the “rapid mobilizing, border sealing, and fire strike [capabilities]” of the PLA, its Southern Theater Command said.

“[Our] troops are always prepared to respond to various unexpected situations and are determined to safeguard [China’s] national sovereignty, border stability, and the safety of people’s lives and property,” a spokesman was quoted as saying on the command’s official WeChat social media account. This is interesting.

China’s live-fire exercise and port calls were clear signals to those inside Myanmar and external forces, including the West, that Beijing will not allow the country to destabilize.

Myanmar is indeed in serious chaos and the military is in a state of decline. Neighbors including China are concerned. Will China take sides with war criminals? Some opposition leaders, hoping that China will support the revolutionary cause, wishfully insist that China has not fully decided on that.