In recent years, Beijing has conducted security and political assessments and concluded that the Myanmar military regime, the State Administration Council (SAC), can no longer protect China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)-related projects in Myanmar. Chinese sources in Beijing familiar with the situation said the SAC was considered too weak and unstable.

This is the main reason behind China’s proposal to the junta to form a joint venture security company (JVSC), which has created headlines in Myanmar media as well as unease among top military leaders in Myanmar.

Myanmar junta’s official announcement on the formation of a Working Committee for Signing a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on establishing a JV security company between Myanmar and China, and The Irrawaddy’s unofficial English translation of the announcement.

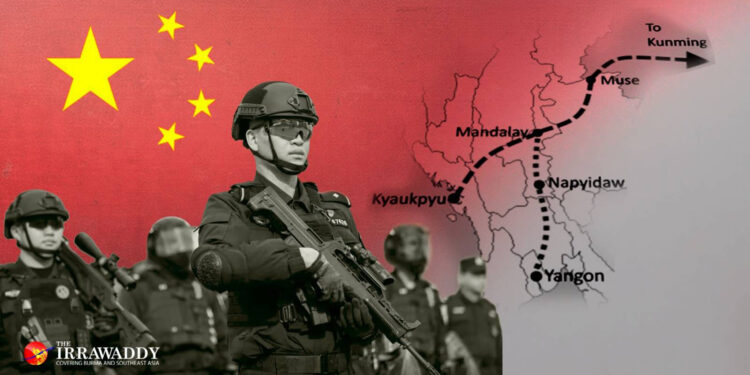

After seeing the fall of northern Shan State capital Lashio in August and the escalation of armed conflict from northern Shan State to central Myanmar to Rakhine (areas through which China-owned oil and gas pipelines pass, as well as a proposed BRI-related railway line that would connect Kunming in China to Rakhine on the shore of the Bay of Bengal)—as well as a bomb attack on the Chinese Consulate in Mandalay—Beijing has been forced to come up with a proposal to defend its projects in Myanmar. It remains to be seen how Myanmar armed opposition groups including ethnic armed organizations and their allies will react to this.

In the wake of the 2021 military coup and the nationwide armed revolt against the regime, China’s BRI projects in Myanmar have been stalled and face security challenges.

Since the launch of the BRI in 2013, Chinese private paramilitary companies have been active around the globe safeguarding China’s mega projects against perceived threats from criminals and violence. These Private Security Companies (PSCs) have been safeguarding Chinese ports and vital sea communication routes, collecting critical local intelligence, and deploying personnel for non-combatant evacuation operations.

Despite being “private”, all Chinese PSCs are under the control of the Chinese government. They are largely made up of former servicemen from China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and police force. They are equipped with modern firearms and sophisticated gadgets for intelligence gathering and communication. In short, PSCs are miniature Chinese armies in disguise dispatched to places where the PLA can’t be deployed.

In fact, some Chinese scholars quietly admit that China’s show of force on the Myanmar border has had no effect at all.

In late August, after the fall of Lashio to resistance ethnic armed groups and their allies, and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to Naypyitaw, Beijing held a live-fire military exercise near its border with Myanmar as a warning sign to the warring groups to maintain stability and security in the border area.

The PLA’s role is to project power and influence around the globe. But on the border with troubled Myanmar, it is not working at all as the fighting has spread and resistance groups have seized enough ground to threaten Myanmar’s second-largest city Mandalay, an observer of China-Myanmar affairs in Beijing admitted.

China has held military drills near the border since fighting on the Myanmar side broke out in 2015. But it has made no difference; the situation has gotten worse with widespread fighting, the junta’s loss of more towns, and regime airstrikes near the border resulting in bombs and bullets landing on Chinese soil.

In July, armed resistance forces seized two Chinese-invested joint ventures—a cement factory in Mandalay and a nickel mining company in Sagaing Region. The fall of Lashio came the next month. China decided “enough is enough” as the situation deteriorated to its lowest point.

In fact, since the live-fire drill held along the border in late August, senior officials in Beijing have been thinking about what new role the PLA can play in the Myanmar conflict to protect Chinese interests. That’s why they came up with the proposal of forming a joint venture security company for the safety of Chinese projects in Myanmar, with Beijing insisting that the junta comply with the proposal, sources said.

In fact, Chinese security guards have been deployed for years at Chinese projects in Rakhine State’s Kyaukphyu. But they are not like the ones from the proposed joint venture security company, who will be equipped with modern firearms and sophisticated intelligence and communications devices.

Yet to be seen is Beijing and Naypyitaw’s joint security plan for Myanmar’s (conflict prone) economic corridor, but it’s too early to make any predictions about that.