The Myanmar military is in serious trouble. Coup maker Senior General Min Aung Hlaing faces growing calls to resign—this time, not just from his opponents, but also from his allies.

Internal dissent, defections and a breakdown in the chain of command. What’s next?

An internal coup?

Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing’s attempts to lead the military and administer the country in the three years since the coup are seen as completely incompetent.

Analysts said removing

Min Aung Hlaing alone

isn’t enough—he and

his entire gang must go.

But if there were to be a coup against him, then what? Would a coup lead to a genuine transition, or would he just be replaced by a hardline faction?

Analysts said removing Min Aung Hlaing alone isn’t enough—he and his entire gang must go. Then, who would hold him and his regime accountable for the crimes committed so far?

In any case, pressure is mounting on the regime and its leader.

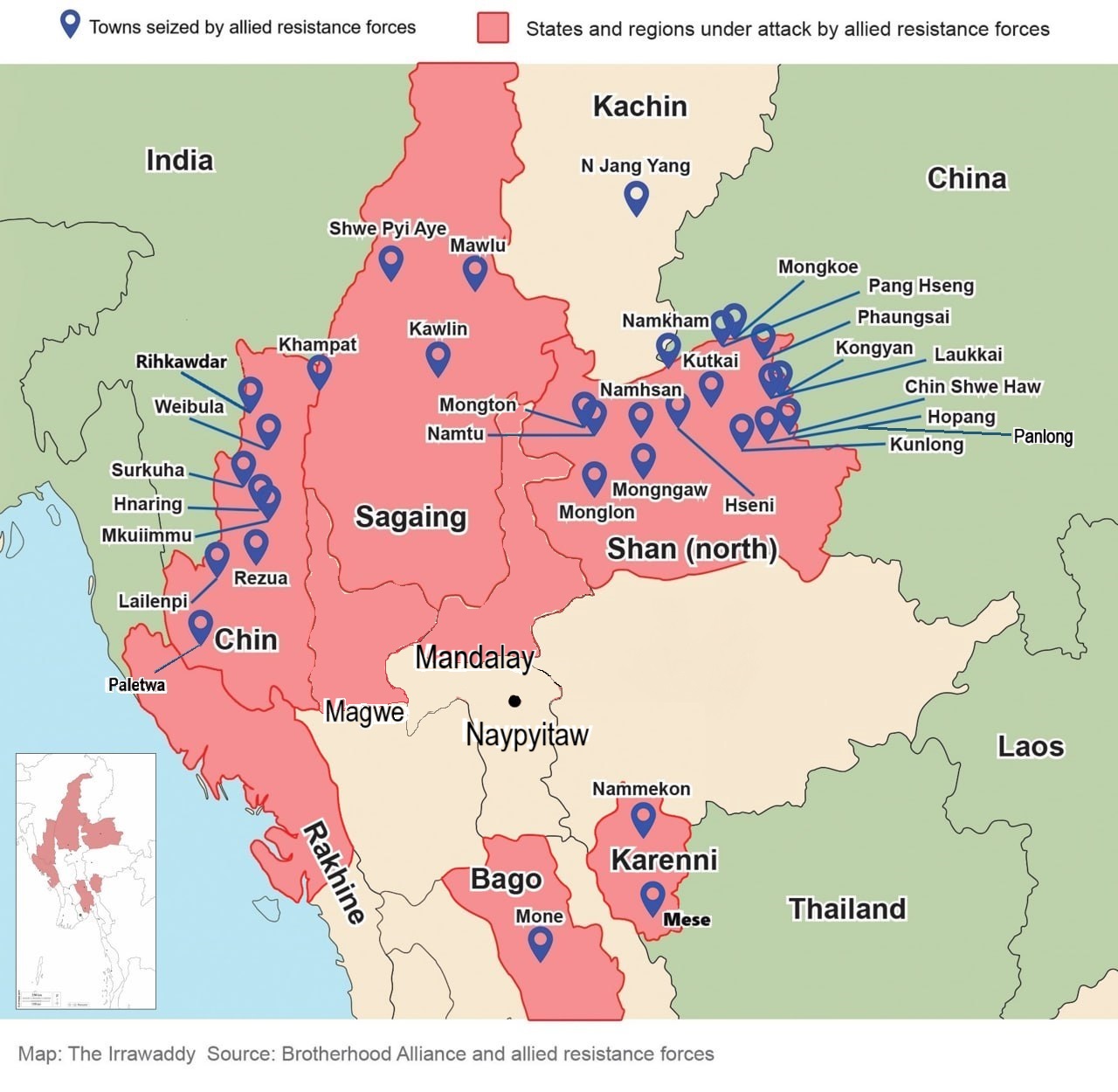

The humiliating defeat in northern Shan State and the severe losses suffered by the military have stirred deep dissatisfaction among rank-and-file soldiers. Ex-military officers have posted comments on social media insisting that commanders who surrender to ethnic armed forces should be harshly punished.

In Naypyitaw, six brigadier generals who surrendered in northern Shan State were given life sentences. Families of officers and soldiers live under serious stress as they face intimidation and the threat of punishment from their superiors.

On the front lines in Rakhine, Karen and Karenni (Kayah) states, troops are divided over whether to fight, remain neutral or compromise.

In recent months, many officers have quietly relocated to neighboring countries Thailand and India.

Seeing the regime’s repeated failures on several fronts, there have been growing calls from pro-regime figures for Min Aung Hlaing to step down.

Last week, an ultranationalist Buddhist monk who helped set up pro-junta militias was detained and questioned by authorities after he joined calls for Min Aung Hlaing to resign to show responsibility for the string of humiliating military defeats.

He told a crowd gathered for a pro-military rally in Mandalay Region’s Pyin Oo Lwin town that Min Aung Hlaing should step down from his post as military chief and hand over control to his deputy, Vice Senior General Soe Win.

The monk, Ashin Ariawuntha, also known as Pauk Ko Taw, was released after being questioned in the morning.

Regime supporters have expressed anger at Min Aung Hlaing publicly, on YouTube and Facebook.

They say he is incompetent, selfish and lacks backbone, and accuse him of guiding a military once considered invincible into a state of shame and desperation.

“Three years is enough for U Min Aung Hlaing” has become their refrain. The timeline refers to the coup the general led in 2021.

He is in deep trouble. Will he step down? Would he allow Soe Win to take over?

Many insiders have said the duo do not have good chemistry. As the hugely unpopular regime has faced crises and losses on the front lines, the two are rumored to have engaged in heated exchanges over the losses and failures. Min Aung Hlaing and his family are known to be very corrupt. Soe Win is regarded as less so, though his family (on his wife’s side) is involved in construction and hotel businesses in Mandalay and Pyin Oo Lwin and mining business in Kachin State. The issue of corruption aside, there should be extensive public hearings about who ordered troops to commit war crimes over the past three years.

The growing calls for Min Aung Hlaing to resign come as the six-month extension period of the legal status of the regime’s governing body, the State Administration Council (SAC), is set to expire on Jan. 31.

To extend the six-month period the regime will have to convene the National Defense and Security Council (NDSC). Acting president Myint Swe is seriously ill, but by hook or by crook, Min Aung Hlaing will do whatever it takes to convene the NDSC meeting.

Analysts say there are a few possible options or scenarios for what might happen next. The first one is for the junta to simply approve another extension. Opposition forces will react with further offensives and the country will continue its steep decline.

The second option would be a major reshuffle, some analysts close to the regime say. This would involve Min Aung Hlaing handing his current position of prime minister to one of the two deputy PMs—Tin Aung San and Mya Tun Oo—while remaining commander-in-chief of the armed forces and chairman of the regime. Such a reshuffle won’t please anyone, however.

Deputy Prime Minister Tin Aung San is an admiral and the regime’s defense minister, while Deputy Prime Minister Mya Tun Oo is a former defense minister and current minister for transport and communications. The latter is known to be a favorite officer of former dictator Than Shwe.

The third scenario is for the regime to allow creditable civilian politicians to form an interim government. Some ethnic armed organizations that have signed ceasefires with the regime have recently suggested that the junta allow the formation of a coalition government.

What about the views of China and Myanmar’s other neighboring countries?

There has been speculation among opposition forces that China wants Min Aung Hlaing removed and a transitional government established.

During his recent visit, China’s Vice Foreign Minister Sun Weidong reportedly met with former dictator Than Shwe at his residence. (China also reportedly asked to see detained State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi but the request was denied.) This is not the first time since the coup that a Chinese official has sought to meet Than Shwe. Several high-level officials from China have met him over the past three years, raising rumors and speculation about his continued influence over the coup leader and the SAC.

The question now is who wants Min Aung Hlaing to remain in power?