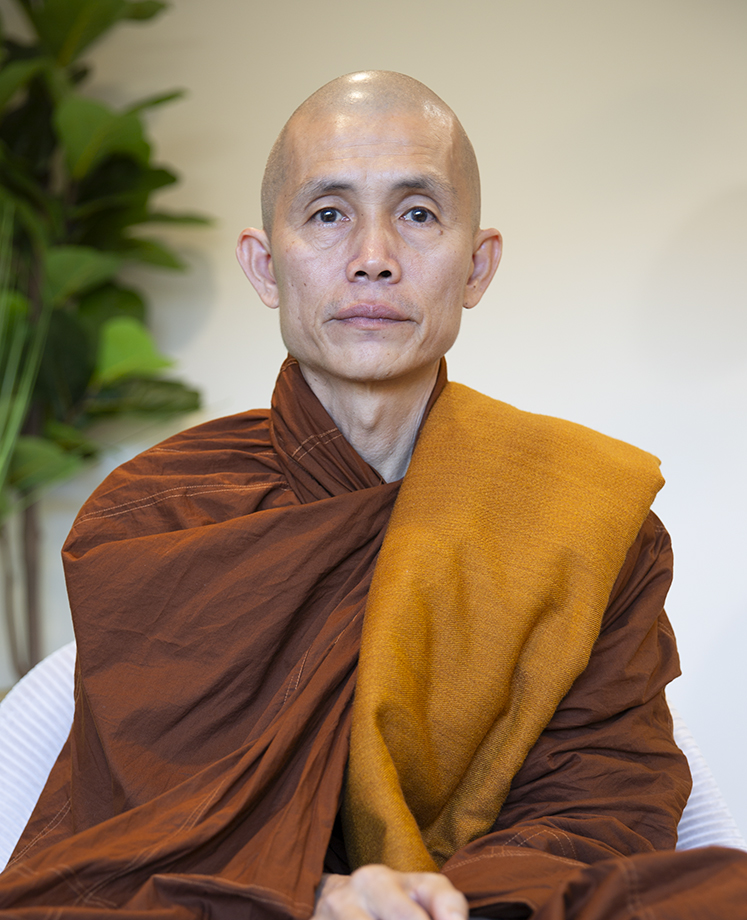

Sayadaw U Ottamathara is well known for his meditation centers and recognized for helping the elderly, the impoverished, and people in need of housing or medical attention. These are the hallmarks that made him famous and highly praised.

But then, he had a sudden fall from grace.

The fall came after his meeting with U Tin Oo, an elder statesman of the National League for Democracy, where he said Daw Aung San Suu Kyi should step aside from politics, and that would bring peace to the country.

Condemnation was immediate and widespread. It sparked a fury against the monk that is likely to be a key part of his legacy.

“When you said that, everything is over. No matter how you try to explain, it is very difficult. Because of what you said the majority of followers consider you no longer a monk.” – Sayadaw Ashin Sarana, in conversation with U Ottamathara, August 2023

U Ottamathara’s position on government is Buddhist-centric. He says that Buddhism in Myanmar is in serious peril and preserving this religious tradition and culture must be the country’s top priority. In his view, having government leaders who understand and promote Buddhism is imperative if this religious tradition is to be preserved. And those who make Buddhism central to their leadership “will win.”

U Ottamathara says the military is not justified in taking over, “that is clear.” He went on to say it’s against Buddhist teachings:

“I am a monk… I will not take what is not given to me. That is the rule for the monks and also the rule for the Buddhist.”

Paradoxically, he firmly asserts the military is beneficial for Buddhism.

“[The] military is maintaining Buddhism. They want Myanmar to be developed as a Buddhist country…. [The] military takeover—religion and culture is the reason why.”

This is a familiar military and Buddhist nationalist refrain and it has been used repeatedly for decades. The generals position themselves as Myanmar’s spiritual guardians of Buddhism because, they say, it is being threatened by Islam and other religions. Nationalist monks support the military by their public presence with the generals and their silence on the military’s atrocities.

“The military is a demonic force that uses Buddhism for political purposes to build power.”—U Mani Sara, a monk imprisoned after attending anti-military rallies. The New York Times, 2021

Monks are on both sides of the political spectrum; many support the military, and many are against it. Monks have consistently been alongside protesters and have been hunted, jailed, humiliated and killed for following their Buddhist teachings. Monks were also some of the most ardent backers of the military’s attempts at ethnic cleansing of Rohingya Muslims.

The military has controlled the country for generations and, according to U Ottamathara, they cannot be ignored. It’s inconceivable to him that the military’s concerns would not be part of any path towards peace.

U Ottamathara’s empathy for the military and displeasure with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is clear. There is an underlying disdain when he talks about Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her “Western influence.”

“For Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, she grew up in the West; [she] is Buddhist, but she may not understand Buddhist culture very well. She may not emphasize traditional Buddhism.”

Religious nationalism is evident in the attention he gives to the West’s influence.

“When she became leader [her ideas were] based on the West, not on the East. If they take help from the West there will be [an] overwhelming of Christians. It used to happen like this.” U Ottamathara believes the West’s influence precludes her from a leadership role where strengthening Buddhism is Myanmar’s most important issue.

He acknowledges that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has been a force for good: he credits her for the country’s economic growth, admits that she increased personal freedom, the free press thrived, and education improved. He also recognizes her National League for Democracy received an overwhelming majority of votes in the 2020 election. But apparently her accomplishments and overwhelming support by the people are not enough for her to lead the country.

Instead, since she is well known and respected, leaving politics and becoming a peacemaker is the best for everyone. But not addressed is why she can’t both lead the country and bring peace to Myanmar.

In U Ottamathara’s self-appointed role as negotiator, he is not shy about saying he is the only one capable of bridging the political gap between the military and the opposition.

In U Ottamathara’s teachings (The Complete Thabarwa, June 2018), he expressed similar beliefs: “We are different but we have the same understanding. This is why we can work together; we will not fight together. Having the same right understanding or right view is the most important.”

Although that sounds like a good teaching, it is unrealistic for Myanmar today. The military’s and the opposition’s “same right understanding” is diametrically opposed.

Burmese groups demonstrated against U Ottamathara when he visited the San Francisco Bay Area in July, 2023. They expressed their outrage loud and clear. Signs read: “Down with Ottama Tharya Supporter of Dictator Killer Min Aung Hlaing! – Get Out! Get Out!! Ottama Tharya! Right Hand of Killer Min Aung Hlaing – STOP Killing our People!! STOP killing our children! – GET OUT, Criminal Fake Monk!!!”

Asked about his understanding of the protesters’ anger, U Ottamathara believes: “They see from the side of the West, the Westerner. In the West, in a developed country, the government and the people emphasize human rights. Everyone is equal. But not in the East; [there is a] different view.”

During a contentious phone call with one of the protesters, he expressed interest in meeting with their group’s leaders. The group declined the meeting unless he publicly denounced Min Aung Hlaing. The protester asked if he cares about the Burmese people. The reply was “of course,” and “Min Aung Hlaing is one of the people.”

There are many monks who vehemently disagree with U Ottamathara’s approach. As a scholar from Buddha University put it: “If he truly has better wishes for the country and if he is actually following the code of conducts and the rules and regulations of Buddhist monks, he should preach [to] the military.”—Sayadaw Min Thonnya

U Ottamathara started his attempts at brokering peace over two years ago, not long after, as he describes it, the “great political change.” To date, no progress is evident in his mediation strategies.

Ottamathara readily says the military’s killings are wrong. That is a mild rebuke of a military that is responsible for killing over 4,100 people and has no intention of stopping their carnage. Because of this, rather than bridging political gaps, he formed a wedge between himself and the wider Burmese communities in Myanmar and around the world.

Gary Rocchio is a freelance photojournalist.