Myanmar’s military regime has resumed a crackdown on unlicensed bureaux de change amid soaring private imports of technology like solar panels.

Some money changers have already gone into hiding as junta officials conduct spot checks and arrests.

On Jan. 14, the regime said it had investigated 26 individuals suspected of illegally buying, selling, and exchanging foreign currency, with nine being prosecuted by the police and six being charged in township courts.

The junta also said it will take action against 12 Facebook groups, five Facebook pages, and 10 individual posters who bought, sold, and exchanged foreign currency online.

Until last week, the unofficial exchange rate was around 4,580 kyats for the U.S. dollar, but it suddenly skyrocketed to 4,615 kyats on Jan. 13 and 4,820 on Jan. 15. After the first wave of arrests, it fell slightly to a range of 4,650–4,680 kyats.

The official exchange rate is a mere 2,000 kyats.

“Many money changers have gone into hiding due to the arrests, and some are greedy and advertise excessive exchange rates on social media,” a money changer in Yangon told The Irrawaddy.

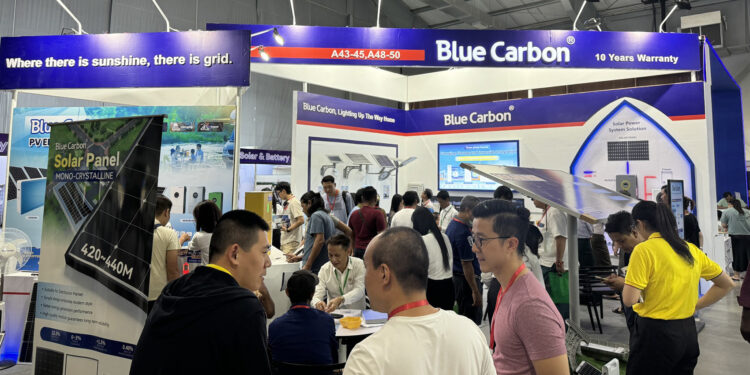

One reason for the dollar’s soaring market price is that demand for foreign technology like solar panels is rising amid chronic electricity shortages.

Electricity is at best available for eight hours a day in Yangon, typically in four-hour chunks, so people are importing generators, solar panels, and battery-powered electrical appliances, according to market sources.

Among the largest importers of solar panels and related products is Aung Pyae Sone, the son of junta chief Min Aung Hlaing, who is profiteering from political instability to import huge amounts of solar products for homes as well as government offices, businesspeople say.

The junta has exempted imports of solar panels and related equipment from customs duties since 2023 to ensure sufficient domestic electricity supply.

After the military seized power, the regime arrested businessmen and formed a committee to monitor and rein in the gold and currency markets, which were soaring as people scrambled for safe havens for their money.

Last year, the regime arrested a dozen gold merchants, including prominent figures such as U Aung San Win, owner of Aung Thamadi Gold Shop, U San Win of Zaw Htet Gold Shop, U Thet Naing Win of Kyan Thone Khway Gold Shop, and U Myo Thu Win, of Academy Gold Refinery, and at least 20 operators of bureaux de change.

Some were released on bail while others had to pay bribes to escape prosecution, according to business sources.

Gold traders are therefore nervous that the current crackdown on money changers could hit them too, one Yangon gold merchant said.

“Some foreign exchange traders have been arrested, but no gold merchants have been arrested yet,” he said. “Gold prices have risen significantly in the global market, and 24k gold is traded on the black market. In theory, gold prices are set by the government, but traders normally do whatever they want. But now they’re being cautious.”

On Jan. 13, the global gold market rose by US$10 to $2,696 per ounce, and the market price in Myanmar rose from 6.4 million kyats per tical of 24k gold to 6.6 million kyats.

But the junta-controlled Gold and Currency Market Monitoring and Regulatory Working Committee set the gold price at just 5.4 million kyats per tical—a gap of almost 1.2 million kyats.

“The new U.S. president will be sworn in on Jan. 20, so the dollar is fluctuating in the global market and in Myanmar as well,” the Yangon money changer said. “The gold price is also soaring due to buying by solar companies, and the regime has arrested some money changers, so everyone is being cautious.”

The junta-controlled Central Bank of Myanmar and the Ministry of Home Affairs are also cracking down on operators of the informal remittance system known as hundi, which is used by migrant workers to send their earnings home at market exchange rates.