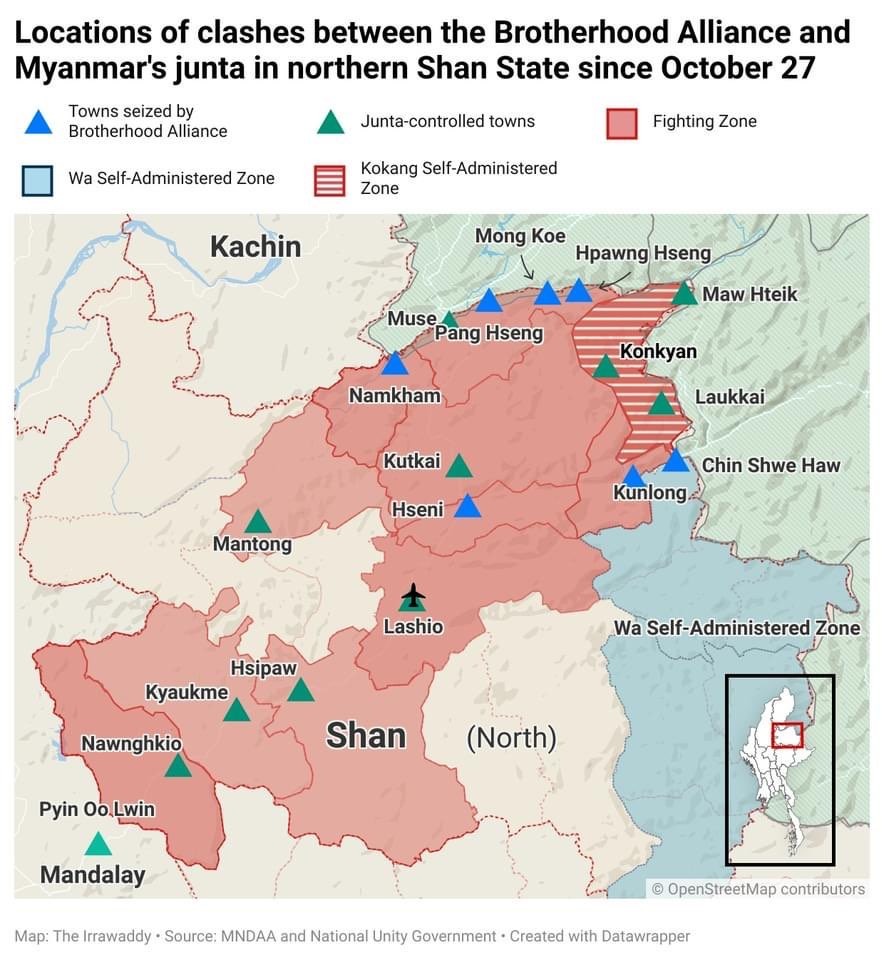

The offensive against the military regime has intensified across Myanmar since the launch of Operation 1027. The regime lost around 200 positions in a month in northern Shan State, where its military forces are in chaos. Observers are well aware that the regime is unable to regain control of those positions.

The offensive has since spread to other parts of the country. Resistance forces have seized Kawlin and Kamphat towns in Sagaing Region, and occupied police stations as well as the bases of junta troops and junta-affiliated militias in Sagaing and Magwe regions. In some cases, junta troops have been forced to abandon their positions because of a shortage of personnel, ceding large swathes of territory to People’s Defense Force groups (PDFs). There have been barely any reports of junta raids and arson attacks on villages in Sagaing and Magwe regions recently. The regime is short of personnel to carry out such raids.

In Chin State, ethnic Chin revolutionary organizations have gained control of much of the territory, seizing Rihkhawdar and Lailinpi towns.

In Karenni (Kayah) State, Karenni resistance forces have seized Mese Township, and are fighting in the state capital, Loikaw. The junta’s administration has collapsed in much of the state.

In Kachin State, junta troops and administrative staff have also been forced to leave Injanyang town. The regime has also lost many bases and crucial transportation routes in Karen State.

In Rakhine State, junta security forces have been forced to abandon at least 40 positions, and its administration has collapsed.

Myanmar’s border trade with China, India and Bangladesh has been halted due to the fighting.

It is indisputable that Operation 1027 has turned the tide of the war against the Myanmar military regime, less than three years after its coup.

False assumptions

When the Brotherhood Alliance launched the operation, the popular view was that China was pulling the strings behind the tripartite military alliance, and that it would stop fighting when China told them to stop—either after it achieved China’s objectives, or when its interests were harmed.

Operation 1027 has however proven to be an ambitious and systematic offensive. It has clear military objectives, and the alliance is determined to attain them. It fought for two days to seize Chin Shwe Haw. It fought for 12 days to seize Kunlong, and it fought for 28 days to occupy Mong Kyat base.

This marks a significant departure from previous operations in which resistance groups would only carry out sneak attacks and withdraw after a while. The alliance is executing a strategy to accomplish its objectives and maintain control of the towns it has occupied.

Junta positions seized by the Brotherhood Alliance are not ordinary outposts, but key bases commanded by battalion commanders, tactical commanders and division commanders. They are command offices and regimental headquarters.

On Nov. 27, as the operation turned one month old, the ethnic alliance declared it was taking things to the next level by launching a nationwide offensive. Large piles of weapons and ammunition including armored vehicles and howitzers seized from some 200 junta positions over the past month will support this.

Chinese rule?

Shortly after the Brotherhood Alliance seized the Jin San Jiao (Kyin San Kyawt) border gate on Nov. 25, China’s People’s Liberation Army announced military exercises along its border with Myanmar. The Chinese Embassy in Yangon has told Chinese citizens to leave Laukkai, the capital of the Kokang Self-Administered Zone in northern Shan State, which the ethnic alliance is planning to attack.

China’s military drills have prompted rumors that Beijing is planning to install its own administrations in towns seized by the ethnic groups, as the alliance lacks administrative capacity.

It is unusual for China to conduct a military exercise when clashes are happening along its border. It is not even responding as strongly as it did when fighting broke out in Kokang in 2015 after the Myanmar military carried out an offensive against the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army there. At that time, China announced live-fire drills and imposed a no-fly zone.

The rumors that China will install administrations in northern Shan State towns have been deliberately spread by the Myanmar military, which always tries to portray itself as the protector of the country, while seeking to exploit anti-China sentiment among Myanmar people.

Indonesia’s statement

Indonesia issued an eyebrow-raising statement on Nov. 25 saying it hosted “positive” talks in Jakarta with interlocutors for the Myanmar military regime, representatives of the parallel National Unity Government (NUG), and armed groups belonging to ethnic minorities.

The NUG said it held separate talks with Indonesia’s Office of the Special Envoy, but denied meeting any representative of the regime. Indonesia’s statement sowed considerable confusion amid high military tensions in Myanmar. Why has the Indonesian Foreign Ministry issued a misleading statement that suggests the likelihood of an inclusive dialogue in Myanmar while its special envoy only held separate talks with some of the country’s key stakeholders?

It is unlikely that Indonesia did so simply to receive credit for taking action on the Myanmar crisis in its final month as the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) chair. Indonesia apparently holds the view that it would be more difficult to resolve the Myanmar crisis if the Myanmar military loses its position of power and the fabric of the country is disrupted. Perhaps this is the reason that drove Indonesia to issue such a statement to facilitate dialogue.

Perceptions of the military

Armed revolts have sprung up across Myanmar since the 2021 coup, but the turning point in the revolt did not come until Oct. 27, 2023.

Observers at home and abroad believed it would be impossible for the resistance to gain the upper hand over the junta’s military. So, they continued to hold the same military-centered view that has been dominant since the political reforms in 2011—that the Myanmar military is the major stakeholder in Myanmar’s crisis.

That notion was still strong when the Myanmar military organized an event to mark the eighth anniversary of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement on Oct. 15, 2023. Not only Myanmar’s neighbors China and India, but ASEAN and even some European countries considered a return to a military-centered peace process.

Operation 1027 however has debunked that notion. A number of towns and some 200 positions in northern Shan State fell in a month.

The fighting is northern Shan shows that the Myanmar military is not unassailable. The reality is that the military is unable to retake control of the towns and positions its has lost in northern Shan State.

Operation 1027 has inspired similar offensives elsewhere across Myanmar. On various fronts, the Myanmar military is collapsing both materially and psychologically.

This rapid deterioration suggests that the Myanmar military can be defeated and could collapse. The military-centered notion has been seriously challenged, shocking those who took it for granted for over a decade, and those who view the Myanmar military as the most important stakeholder in the country.

Unable to accept the loss of the military’s position

Not only the Myanmar military and its sympathizers, but also many observers at home and abroad are concerned about the possibility of the military losing its position. Only a few observers changed their viewpoints after the 2021 putsch. The majority of observers still held the view that the Myanmar military is the key player in solving the country’s crisis.

This is not surprising given that the Myanmar military retained its grip on power for more than six decades and made careful propaganda efforts all those years. The so-called pundits were apparently confused by this distorted history.

When it comes to dissidents and armed groups called “rebels” by the Myanmar military, such pundits tend to find fault with them, and jump to conclusions. But they failed to notice the cancer within the Myanmar military that has held power for so many years, and they are not willing to accept it now that the defects of the Myanmar military have finally been exposed. They cling to the belief that only the Myanmar military can resolve the crisis in the country.

After witnessing a turning point in the post-coup war, they are no longer promoting the view that the Myanmar military will ultimately be able to keep things under control. But, they still hold the view that Myanmar’s powerful neighbors will intervene in the country’s affairs, or that the country will break up when the Myanmar military ceases to exist.

In a last-ditch effort, they have called for giving the Myanmar military some room to withdraw. They are trying to save the military rather than the Myanmar people. In fact, the 2008 Constitution serves as a tool that the Myanmar military can use to get itself out of the crisis.

Junta boss Min Aung Hlaing, who once said, “There is nothing I won’t dare to do,” and his followers staged the coup, thereby cutting off any route for themselves to retreat. Observers are in fact calling for resurrecting a dead tiger.

It is time for such observers to change their view, and re-center their approach around the Spring Revolution forces and the Myanmar people. They need not fear the chaos that follows change. When the Wa people split from the Communist Party of Burma, many people believed they would get into trouble. But 30 years on, they have built a strong institution and secured their territory.

When it comes to resolving Myanmar’s issues, there won’t be solutions unless the military-centered approach is abandoned. As long as we cling to the crumbling institution of the Myanmar military, we won’t be able to objectively judge Myanmar’s issues.

Wai Min Tun is a political analyst.