HONG KONG — If the People’s Liberation Army went to war tomorrow, it would field an arsenal bristling with hardware from some of America’s closest allies: Germany, France and Britain.

Most of China’s advanced surface warships are powered by German and French-designed diesel engines. Chinese destroyers have French sonar, anti-submarine-warfare helicopters and surface-to-air missiles.

Above the battlefield, British jet engines drive PLA fighter bombers and anti-ship strike aircraft. The latest Chinese surveillance aircraft are fitted with British airborne early warning radars. Some of China’s best attack and transport helicopters rely on designs from Eurocopter, a subsidiary of pan-European aerospace and defense giant EADS.

But perhaps the most strategic item obtained by China on its European shopping spree is below the waterline: the German-engineered diesels inside its submarines.

Emulating the rising powers of last century—Germany, Japan and the Soviet Union—China is building a powerful submarine fleet, including domestically built Song and Yuan-class boats. The beating hearts of these subs are state-of-the-art diesel engines designed by MTU Friedrichshafen GmbH of Friedrichshafen, Germany. Alongside 12 advanced Kilo-class submarines imported from Russia, these 21 German-powered boats are the workhorses of China’s modern conventional submarine force.

With Beijing flexing its muscles around disputed territory in the East China Sea and South China Sea, China’s diesel-electric submarines are potentially the PLA’s most serious threat to its American and Japanese rivals. This deadly capability has been built around robust and reliable engine technology from Germany, a core member of the US-led North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Arms trade data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) to the end of 2012 shows that 56 MTU-designed diesels for submarines have been supplied to the Chinese navy.

“They are the world’s leading submarine diesel engines,” says veteran engineer Hans Ohff, former managing director of the Australian Submarine Corporation, the company that built Australia’s Collins-class conventional submarines.

MTU declined to answer questions about transfers to the Chinese navy, future deliveries or whether it supplies technical support or servicing. “All MTU exports strictly follow German export laws,” a company spokesman said.

China’s Military Market

The Chinese defense ministry says the PLA’s dependence on foreign arms technology is overstated. “According to international practice, China is also engaged in communication and cooperation with some countries in the area of weaponry development,” the ministry said in a statement responding to this series. “Some people have politicized China’s normal commercial cooperation with foreign countries, smearing our reputation.”

Transfers of European technology to the Chinese military are documented in SIPRI data, official EU arms trade figures and technical specifications reported in Chinese military publications.

These transfers are crucial for the PLA as it builds the firepower to enforce Beijing’s claims over disputed maritime territory and challenge the naval dominance of the US and its allies in Asia.

China now has the world’s second-largest defense budget after the United States and the fastest growing military market. Many of Europe’s biggest defense contractors have been unable to resist its allure. High-performance diesels from MTU and French engine maker Pielstick also drive many of China’s most advanced surface warships and support vessels, SIPRI data shows. Pielstick was jointly owned by MTU and German multinational Man Diesel & Turbo until 2006, when Man took full control.

Some military analysts remain skeptical about the quality of China’s military hardware. They say the engines and technology the PLA is incorporating from Europe and Russia fall short of the latest equipment in service with the United States and its allies in Asia, including Japan, South Korea and Australia. This leaves the PLA a generation behind and struggling to integrate gear from a range of different suppliers, they say.

Others counter that China doesn’t need to match all of the most complex weapons fielded by the United States and its allies. Even if it deploys less than the best gear, Beijing can achieve its strategic goal of blunting US power.

“At what point do they become good enough?” says Kevin Pollpeter, a specialist on Chinese military innovation at the University of California Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation at San Diego. “If they have sufficient quantities of good-enough weapons systems, maybe that will carry the day.”

Limits of Embargo

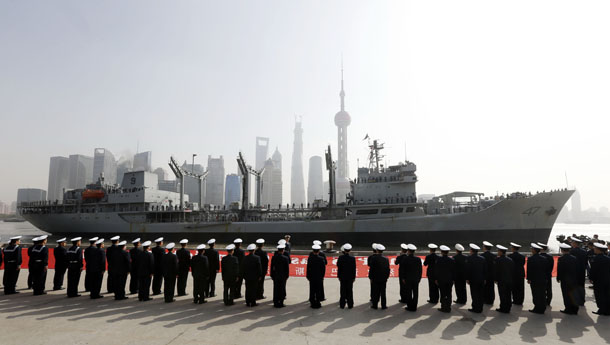

Russia remains China’s most important outside source of arms and technical assistance. The Chinese navy’s best-known vessel—its sole aircraft carrier, the Liaoning—was purchased from Ukraine. A US Navy vessel nearly collided with a Chinese warship last week while maneuvering near the Liaoning, during a time of heightened tensions over Beijing’s recent declaration of a new air-defense zone in the East China Sea.

European hardware and know-how fills critical gaps, however. It wasn’t supposed to play out this way.

The European Union has had an official embargo on arms shipments to China since the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown. Washington imposes even tighter restrictions on transfers of US military technology to China, inspiring energetic efforts by Beijing to smuggle American gear and know-how. Europe’s embargo, however, has been far more loosely interpreted and enforced. Thus weapons and, perhaps more importantly for the PLA, dual-use technology have steadily flowed from America’s European allies to China.

EU arms makers have been granted licenses to export weapons worth almost 3 billion euros (US$4.1 billion) to China in the 10 years to 2011, according to official figures from Brussels collated by the London-based Campaign Against Arms Trade. EU governments approved the sale of aircraft, warships, imaging equipment, tanks, chemical agents and ammunition, according to official figures.

Michael Mann, an EU spokesman in Brussels, said the EU arms embargo issued in June 1989 “does not refer to dual use goods.” It is up to individual member states to exercise control over such goods, Mann said.

From China’s perspective, France and the UK interpret the arms embargo most generously, mostly blocking only lethal items or complete weapons systems. France was by far the biggest EU supplier, accounting for almost 2 billion euros of these licenses. The United Kingdom ranked second with almost 600 million euros, followed by Italy with 161 million euros. The value of weapons actually shipped is difficult to extract from the data because some countries, including the UK and Germany, don’t report these figures.

The value of German export licenses for weapons was a relatively modest 32 million euros in the decade to 2011. However, EU arms trade figures don’t include dual-use technology that in many cases can be sold without licenses. Examples of such technology include many kinds of diesel engines. The same applies to transfers of commercial aerospace design software that can be used for fighters, bombers and unmanned aerial vehicles.

Arms industry experts say dual-use transfers are almost certainly more valuable to the PLA than the actual weapons Europe has delivered. But it’s impossible to calculate a hard number for European-Chinese trade: The EU lacks a consistent system for tracking these transfers amid the vast flow of goods, services and intellectual property to China. Europe shipped goods worth 143.9 billion euros to China in 2012, according to EU trade statistics.

Critics of the EU’s arms trade with China say member states have failed to devise a system to enforce the embargo. They say this reflects the loose structure of the EU, where each member state interprets the restrictions differently according to domestic law, regulations and trade policies.

Geography plays a role, too: The distance between Europe and Asia means there is ambivalence about the rapid growth of Chinese military power. From Europe, China looks like an opportunity, not a threat.

Selling Components

The embargo is nevertheless an embarrassment for Beijing; senior Chinese officials routinely call for it to be lifted, and pressure from Washington keeps it in place. That means the sale of complete weapons like the pan-European Eurofighter, German submarines or Spanish aircraft carriers remain impossible for the foreseeable future.

In the meantime, Europe has discovered a lucrative trade selling components, particularly if they incorporate dual-use technologies that fall outside the embargo.

“Nobody sells entire weapons systems,” says Otfried Nassauer, director of the Berlin Information Centre for Transatlantic Security and an expert on Germany’s arms trade. “But components, especially pricey high tech components, that works OK.”

Under Beijing’s long-term policies to promote innovation, domestic arms makers are encouraged to import the foreign technology that China lacks. The challenge is to adapt this range of components and know-how into locally built weapons.

One example is how German engine makers have contributed technology to support China’s expanding fleet of support vessels that monitor satellites and missiles.

Man Diesel & Turbo last year announced it would supply engines built under license in China for two new transport vessels for the China Satellite Maritime Tracking and Controlling Department, part of the PLA’s General Armament Department (GAD). The GAD oversees weapons research and development and manages all of China’s military and civilian space operations, including the tracking of satellites and missiles. The European engine maker will also supply gear boxes, propellers and propulsion control systems for the ships from its Danish manufacturing unit, it said.

A spokesman for Man Diesel & Turbo said about 250 of its engines had been made under license in China and supplied to the Chinese navy. The company also provided some selected services and spare parts including fuel equipment.

“All our business does fully comply with the applicable export control or embargo regulations set by Germany and the European Union,” the spokesman said. He added that Pielstick brand engines supplied to the PLA navy by Chinese licensees were not subject to export approval. “None of these engines is specifically designed for military purposes,” he said. “There is a broad variety of civil applications for these engines, too.”

Underwater Disaster

Reliable submarine engines top Beijing’s shopping list, and China’s navy has good reason to want the best.

In the late spring of 2003, a disabled Chinese submarine was found drifting, partly submerged, in the Bohai Sea off China’s northern coast. When the boat was raised, rescuers found all 70 of its crew dead. Their deaths were blamed on “mechanical difficulties,” according to reports at the time in China’s state-controlled media. The outcome of any inquiry was never made public.

Since then, submariners all over the world have speculated about what went wrong aboard Ming class submarine number 361, a Chinese copy of an obsolete Russian design. Most agree it was probably a fault with its diesels. The engines either didn’t shut down immediately when the submarine submerged, sucking the oxygen out of the hull in minutes, or the suffocating exhaust vented internally rather than outside the hull. Either way, the outcome was catastrophic.

It was one of Communist China’s worst peacetime military disasters, and the navy chief and three other senior officers were sacked. But the People’s Liberation Army navy was already taking delivery of diesels from MTU. Engineers at the Wuchang Shipyard on the Yangtze River were fitting these power plants in China’s first indigenously designed and built conventional submarines, the Song class.

MTU is a unit of Germany’s Tognum Group, which is jointly owned by UK-based multinational Rolls Royce Group PLC and Germany’s Daimler AG. Contracts with the PLA and powerful defense manufacturers give MTU and its parent influence in competing for contracts in China’s massive civilian market. China’s biggest arms maker, China North Industries Group Corporation, or Norinco, has been making MTU engines under license since 1986.

In 2010, Tognum opened a joint venture with Norinco to assemble large, high speed MTU diesel engines and emergency generators at a plant in the city of Datong in Shanxi Province. A major goal of the joint venture is to win orders for emergency backup generators for China’s expanding roster of nuclear power plants, Tognum said in a press statement. MTU engines are also built under license at the Shaanxi Diesel Engine Heavy Industry Co Ltd, a subsidiary of one of China’s two sprawling military and commercial shipbuilders.

Submarine diesel technology is hardly new, but these engines are built to exacting standards to ensure reliability under extreme conditions. MTU has been building them for more than 50 years. The engine delivered to China for the Song and Yuan classes, the MTU 396 SE84 series, is one of the world’s most widely used submarine power plants. Each of the Chinese submarines has three MTU diesels, according to technical specifications listed in Chinese military affairs journals and websites.

China’s military is reluctant to acknowledge the role of foreign technology in its latest weapons, preferring to recognize the performance of its domestic designers and arms makers. But articles in maritime magazines and naval websites have credited the close relationship between MTU and China’s domestic industry for providing the Song class with “the world’s most advanced submarine power system.”

In its promotional brochures, MTU says almost 250 of these engines in service with submarines around the world have racked up over 310,000 hours in operation. Some have also been fitted to nuclear submarines as back-up power plants, the company says. MTU also sells different versions of the 396 series for use in locomotives, power generation and mining.

A spokesman for the Federal Office for Economics and Export Control (BAFA), the German authority that has to approve dual-use exports, said exports of diesel engines built especially for military use would be illegal. Engines that can be used for both civilian and military purposes would have to be approved by BAFA, he said – and in the case of China, such dual-use engines “would probably not be approvable.” He declined to comment specifically, however, about the MTU diesel engine sales to China’s navy.

Stealthy Submarines

Top quality diesel engines like the MTU designs minimize vibration and noise, reducing the risk of detection by enemy sonar. In the hands of a capable crew, modern diesel submarines can be fiendishly difficult to detect. When using their electric motors, they are significantly stealthier than nuclear submarines such as those in service with the United States, naval warfare experts say. For a relatively modest investment, a diesel electric sub could sink a hugely expensive aircraft carrier or surface warship.

With whisper-quiet engines, China’s best conventional submarines armed with modern torpedoes and missiles may pose the biggest danger to any potential adversary –including the US Navy. Beijing’s naval strategists are banking on their growing fleet of subs to keep the Americans and their allies far away from strategic flashpoints in the event of conflict, such as Taiwan or disputed territories in the East China Sea and South China Sea.

That means the Pentagon’s favored method of modern warfare—parking carriers near the coast of an enemy and conducting massive air strikes—would be very risky in any clash with China.

The PLA navy has already demonstrated this capability. In 2006, a Song class submarine shocked the US Navy when it surfaced about five miles from the US aircraft carrier Kitty Hawk, well within torpedo range, in waters off the Japanese island of Okinawa. The Chinese boat had been undetected while it was apparently shadowing the US carrier and its escorts, US officials later confirmed.

PLA submarines are becoming much more active. Recorded Chinese submarine patrols increased steadily from four in 2001 to 18 in 2011, according to US Naval Intelligence data supplied in response to freedom of information requests from a Federation of American Scientists researcher, Hans M. Kristensen.

A senior US Navy official declined to comment on German delivery of diesel engines to China, but said the United States is well aware of the challenges such submarines pose. “Diesel engines are notoriously difficult to detect, but we are also always investing in improving own capabilities to make our submarines quieter,” the official said.