In this cover story first appeared in Oct, 2007 print issue of The Irrawaddy Magazine, Kyaw Zwa Moe, the editor of the magazine (English edition), writes about women’s forefront involvement to combat and promote democracy in Burma.

In this cover story first appeared in Oct, 2007 print issue of The Irrawaddy Magazine, Kyaw Zwa Moe, the editor of the magazine (English edition), writes about women’s forefront involvement to combat and promote democracy in Burma.

The women of Burma have always been a force to reckon with

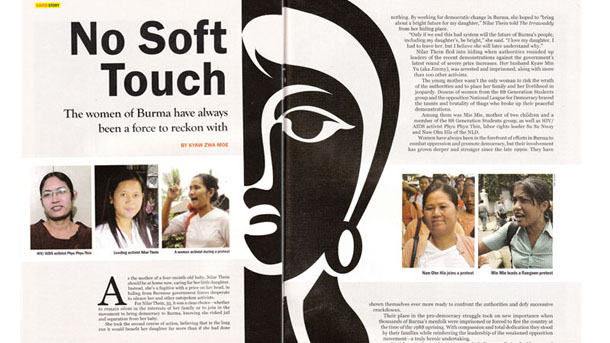

As the mother of a four-month-old baby, Nilar Thein should be at home now, caring for her little daughter. Instead, she’s a fugitive with a price on her head, in hiding from Burmese government forces desperate to silence her and other outspoken activists.

For Nilar Thein, 35, it was a clear choice—whether to remain silent in the interests of her family or to join in the movement to bring democracy to Burma, knowing she risked jail and separation from her baby.

She took the second course of action, believing that in the long run it would benefit her daughter far more than if she had done nothing. By working for democratic change in Burma, she hoped to “bring about a bright future for my daughter,” Nilar Thein told The Irrawaddy from her hiding place.

“Only if we end this bad system will the future of Burma’s people, including my daughter’s, be bright,” she said. “I love my daughter. I had to leave her, but I believe she will later understand why.”

Nilar Thein fled into hiding when authorities rounded up leaders of the recent demonstrations against the government’s latest round of severe price increases. Her husband Kyaw Min Yu (aka Jimmy), was arrested and imprisoned, along with more than 100 other activists.

The young mother wasn’t the only woman to risk the wrath of the authorities and to place her family and her livelihood in jeopardy. Dozens of women from the 88 Generation Students group and the opposition National League for Democracy braved the taunts and brutality of thugs who broke up their peaceful demonstrations.

Among them was Mie Mie, mother of two children and a member of the 88 Generation Students group, as well as HIV/AIDS activist Phyu Phyu Thin, labor rights leader Su Su Nway and Naw Ohn Hla of the NLD.

Women have always been in the forefront of efforts in Burma to combat oppression and promote democracy, but their involvement has grown deeper and stronger since the late 1990s. They have shown themselves ever more ready to confront the authorities and defy successive crackdowns.

Their place in the pro-democracy struggle took on new importance when thousands of Burma’s menfolk were imprisoned or forced to flee the country at the time of the 1988 uprising. With compassion and total dedication they stood by their families while reinforcing the leadership of the weakened opposition movement—a truly heroic undertaking.

“An idea or action tends to come out of a feeling or suffering,” said respected Burmese author Kyi Oo. “They [Burmese women] have faced hardships and lengthy imprisonment. Their unusual dedication and sacrifice came out of such hardships.”

The 83-year-old veteran author of several books on Burma’s women expressed admiration for the efforts of Nilar Thein and her fellow activists, Phyu Phyu Thin, Mie Mie, Su Su Nway and Naw Ohn Hla.

Nilar Thein’s struggle for a just society is rooted in her experience of the 1988 uprising, when she witnessed how government soldiers killed, beat and arrested demonstrators outside her Rangoon home.

“I still hear those voices in my ears and see those scenes in my mind,” she said. “I desperately want to get rid of this evil system.”

During a 1996 demonstration, Nilar Thein was prompted to slap Rangoon’s police chief, who repeatedly ordered his troops to beat her. The police officers at first ignored the order, but when she slapped the police chief she was thrown into a vehicle and driven away to jail. She was sentenced to three years imprisonment for slapping the police chief and to a further seven for her political activities.

Nilar Thein spent eight years and nine months in two notorious prisons, Insein and Tharawaddy. She emerged from jail with her spirit unbroken and her determination to work for democracy as strong as ever.

“The benevolence of those young women towards the country is invaluable,” said Kyi Oo.

Nilar Thein also appears to be invaluable to the authorities, who have offered a reward of several hundred thousand kyat for her capture. Photographs of her and other wanted activists have been widely distributed by the security forces, whose lack of success in tracking most of them down speaks volumes for the amount of popular support the fugitives enjoy.

The wanted activists were even able to continue their campaign by telephone from their hiding places until the authorities blocked their numbers and those of their activist contacts.

In one phone conversation, HIV/AIDS activist Phyu Phyu Thin, 35, explained why young women with families to care for were so actively engaged in the struggle. Their feminine nature, their “sympathy and emotion,” drove woman to “sacrifice,” she said.

Phyu Phyu Thin was first arrested in September 2000, along with 30 women members of the NLD, when they gathered at Rangoon railway station to say farewell to party leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who was heading to upper Burma. The group spent the next four months and four days in an annex of Rangoon’s Insein Prison.

Like Nilar Thein before her, Phyu Phyu Thin’s resolve to fight official misrule and injustice remained unshaken after her time in prison. She determined to devote her entire life to the pro-democracy movement.

The junta’s attempt to break her spirit had misfired—“That’s their mistake,” Phyu Phyu Thin laughed. Before her arrest she had worked only occasionally at the NLD headquarters. After her prison experience, she rarely missed a single day.

That prison experience transformed her feminine compassion and emotion into a stronger commitment. She recalled such injustices as the case of three sisters who played no part in politics but who had been sent to prison because their brother had participated in an anti-junta demonstration in Japan.

Phyu Phyu Thin has won many sympathizers because of her work with HIV/AIDS patients, and when she was arrested again last May they demonstrated successfully for her release.

During last month’s demonstrations she was sheltered by one patient, who told her: “You shouldn’t be arrested.” Over the past five years, Phyu Phyu Thin has cared for about 1,500 patients who were neglected by the state.

The number of women political prisoners in Burma exceeds 50, according to the Thailand-based Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma). The association estimates that since the 1988 uprising, more than 500 women have served prison terms because of their political involvement.

The roots of women’s involvement in politics and power-wielding in Burma go very deep, reaching back several centuries.

In the Pagan era, from the 11th to the 13th century, Queen Pwa Saw’s just reign won the affection and respect of male rulers. Queen Shin Saw Pu, who ruled the Mon Kingdom from 1453 to 1472, was also famous for her effective governance.

Two queens of the Konbaung period (1752-1885)—Nanmadaw Me Nu and Sin Phyu Ma Shin—won respect for their strong will and effective involvement in government. Burma’s last queen, Supayalat, exercised great power over King Thibaw and worked closely with ministers in managing the affairs of state.

Women took to the battlefield in early military encounters with British colonialists. At the time of the First Burma War in 1824, the courage of ethnic Shan women won the admiration of a British officer, Major Snodgrass, who wrote about the 1825 battle of Wethtikan in his book “Narrative of the Burmese War”: “These warrior women wore armor and as they rode their horses bravely, spoke words of encouragement to the soldiers…one of the fair Amazons also received a fatal bullet in the breast.”

At the start of the 20th century, the anti-colonial movement was strengthened by the participation of educated women. In 1919, female intellectuals established Burma’s first national women’s organization, Konmari, and one year later student members of the group joined in the first university boycott against the British.

Opposition to British colonialism was also the agenda of other women’s organizations, such as the Myanmar Amyothamii Konmari Athin (Burmese Women Association) and the Patriotic Women’s Association.

Taking a lead from their menfolk, who adopted the honorific Thakhin, meaning master, in an act of open defiance to the British, women came to call themselves Thakhinma.

A number of women were jailed for their political activity. Thakhinma Thein Tin achieved fame for her defiance of the British and was among the first group of five women to be imprisoned.

As opposition to British rule grew, Burmese women began to claim a place in the international arena. The National Council of Women of Burma, founded in 1931, successfully pressured the British government to admit a Burmese woman delegate to a special Burma roundtable conference in London.

The council’s choice was Mya Sein, an author, teacher and mother, known as M.A. Mya Sein because of the master of arts degree she had obtained from Oxford University. Earlier in 1931, she was selected as one of the two representatives for women across Asia for the League of Nations, the world organization that preceded the United Nations.

At the London roundtable, Mya Sein called on the British government to enact a law guaranteeing equal rights for women in Burma.

In 1929, Hnin Mya was elected Burma’s first woman senator. Another distinguished female senator, Dr Saw Hsa, elected in 1937, was made a Member of the British Empire, a prestigious civil honor.

In 1953, five years after Burma gained independence, another leading woman politician, Ba Maung Chain, was chosen as a minister to represent Karen State, Burma’s first (and only) woman minister.

The role of women in Burmese politics diminished following the 1962 military coup that brought Ne Win to power. Women became little more than puppets in the male-dominated administration. The period between 1962 and 1988, when Ne Win relinquished power after a national uprising, can be seen as a feminine “dark age” in Burma.

Under the current military regime, women haven’t fared much better, and none occupies any high position in government.

The year 1988, however, did see the arrival on the political stage of a charismatic female leader—Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of independence hero Aung San. She became the focus of a nationwide movement for political change and was adopted as a role model for progressive young people in Burma.

Nilar Thein and Phyu Phyu Thin both name Suu Kyi (or “auntie,” as they affectionately call her) as their role model. Like them, Suu Kyi sacrificed family and a secure home life for the cause of justice and freedom.

Suu Kyi declined the opportunity to live abroad with her British husband, Michael Aris, and their two children, choosing house arrest in Rangoon instead. When her husband died she declined to leave the country to attend his funeral, fearing that she would not be allowed to return. She hasn’t seen her two sons for a number of years.

“The dawn rises only when the rooster crows,” Suu Kyi declared in a video-recorded speech to an NGO Forum on Women in Beijing in 1995, quoting an old Burmese proverb. “It crows to welcome the light that has come to relieve the darkness of night.”

Then she added: “It is not the prerogative of men alone to bring light to this world. Women with their capacity for compassion and self-sacrifice, their courage and perseverance, have done much to dissipate the darkness of intolerance and hate, suffering and despair.

“Many of my male colleagues who have suffered imprisonment for their part in the democracy movement have spoken of the great debt of gratitude they owe their womenfolk, particularly their wives, who stood by them firmly, tender as mothers nursing their newly born, brave as lionesses defending their young.”

Suu Kyi referred to the results of scientific research to argue that women were perhaps better able than men to solve issues without conflict. One study found that women were better than men at verbal skills, while men tended towards physical action.

“Surely these discoveries indicate that women have a most valuable contribution to make in situations of conflict, by leading the way to solutions based on dialogue rather than on viciousness or violence,” Suu Kyi suggested.

Women like Suu Kyi and those now in hiding from the authorities can certainly claim the moral high ground in the current political crisis in Burma. Their compassion for the victims of a male-dominated, repressive regime is seen as an important political weapon.

“I love my daughter, but I also need to consider mothers fleeing with their children and hiding in jungles, such as in Karen State because of the civil war,” said Nilar Thein. “My suffering is very small compared to theirs.

“Compared to their children, my daughter still has a secure life with her grandparents, even though I’m not there.”

By allowing concern for one’s own family to divert attention from the hardships of others “we will face more terrible suffering in the future,” Nilar Thein said. “And then my daughter will not be able to enjoy a good life.”