To mark the 32nd anniversary of the ’88 uprising this month, we revisit a foreign journalist’s recollection of clandestine visits to Myanmar to report on the country during an historic period of upheaval. It was originally published in the August 2008 issue of The Irrawaddy Magazine.

WORD reached Bangkok in late August 1987 that the Burmese economy was grinding to a standstill, and that the rice harvest could be compromised by weak rainfalls in some areas. As a reporter who liked to operate alone, I was assigned by Asiaweek, the Hong Kong-based newsweekly, to slip into the country. I would get no byline, no credit, not much pay, but a lot of satisfaction.

It was a memorable week. I made it up to Mandalay on my own, just in time for what some believed was the heaviest rainfall since the end of World War II. These things are hard to gauge, of course, but there was no mistaking the joy the people felt at the suddenly rain-swollen paddy fields. I returned to Rangoon and the care of my wonderful Burmese translator and fixer.

He graciously introduced me to his family, fed me in his home, took me everywhere, persuaded an unwitting former minister of education to buy me a beer and even smuggled me to the ancient capital of Pegu for an audience with His Holiness Eindhasara, or Sayadawgyi, as he was addressed with both affection and respect.

At 91, as head of the Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee, he was the most senior monk in the land and had been abbot of the same temple since 1941. He had never met a foreign journalist before, but even so, for him the encounter was a minor curiosity. For me it was an unexpected honor—a kind of benediction.

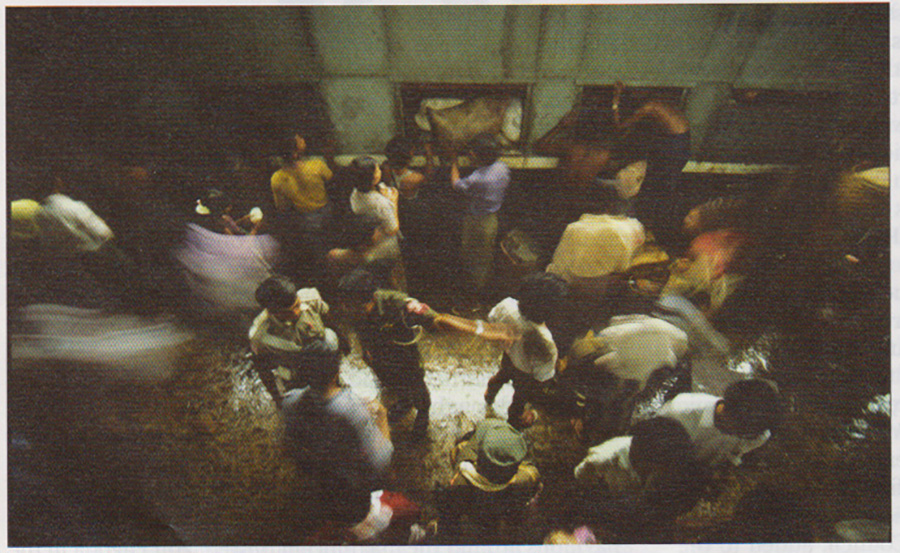

My fixer’s father suddenly took ill. He was reduced to chasing around Rangoon in a desperate search for medicine that could only be found on the black market, if at all. I had already witnessed scuffles that week near a train that was carrying rice into the countryside. When I returned to Bangkok, I knew that even with a few beneficent cloud bursts, times were tougher than ever for ordinary Burmese people and something was brewing behind the scenes.

As it turned out, I had missed one of the country’s biggest stories in decades by one day. Student-led demonstrations unexpectedly broke out on September 5 when the government demonetized large denomination bank notes without warning. There was no hint of the demonetization from anyone during my week inside the country. It was nothing more than state-sanctioned theft. Many people lost their meager savings in one swift stroke.

In the intervening 20 years, the authorities seem to have learned almost nothing about public relations and financial management. In August 2007—again without warning—they suddenly laid down huge increases in diesel and petrol prices, driving the long-suffering populace to the edge once more. There were massive demonstrations again, spearheaded by columns of monks, particularly in Rangoon where up to 100,000 people took to the streets.

Back in 1988, the pressure for much larger nationwide demonstrations had been building through a succession of incidents in Rangoon teashops and outlying areas. Stoking the popular discontent among even the most tolerant of people was a growing realization: Breathtaking economic mismanagement during General Ne Win’s years following the 1962 coup had reduced a fundamentally wealthy nation to pauper status. The UN had classified Burma as a least developed country. Aung Gyi, a disillusioned former member of General Ne Win’s Revolutionary Council, added to the discontent through a series of public, widely disseminated, critical letters.

Average people yearned for democracy, freedom and the other benefits of more politically advanced countries. But first they wanted to eat and dress better, to educate their children, read newspapers, travel, look after their sick and put a proper roof over their heads. In 1988, the demands were uncomplicated and entirely reasonable. Yet in 2008, they still remain unmet.

By July 1988, the discontent was starting to boil over. There was no question that major demonstrations would erupt. Towards the end of the month, Ne Win finally resigned as chairman of the inept Burma Socialist Programme Party. His strange parting words were a call for multi-party democracy followed with a dire warning that the Burmese Army would never hesitate to shoot demonstrators. Ne Win was always bigger on sticks than carrots.

Foreign journalists and photographers had been entering Burma all through the month from Bangkok, trying to figure out when the volcano would blow. With only a seven-day visa available, timing was everything. Nobody was there officially and filing stories was a nightmare. Much of the underground student activity was carried out on campuses and in the pavilions around the magnificent Shwedagon Pagoda in the center of the city. Just like today, small groups would rally, and then people would post revolutionary messages around the city. Everybody knew it was coming.

Although the harshest, anti-government sentiment was passed on by word of mouth, it was the BBC that finally communicated one of the most crucial pieces of information: the demonstrations would begin on the morning of August 8, in other words on 8/8/88.

The report came from a young correspondent, Christopher Gunness. Though it was a first-rate piece of news reporting precisely reflecting the word on the street, the Burmese authorities have since attempted to misrepresent it as evidence of some kind of international conspiracy. The BBC did not call for demonstrations. It merely announced the date they were due to begin. That did, of course, make it pretty official. Nobody believed a word in the state media—everybody listened to the BBC. Indeed, the Burmese Service’s postbag was reputed to receive as much mail as the rest of the corporation’s broadcast services put together.

Later, I often filed freelance reports for the BBC’s Burmese Service. However, I lost count of the number of Burmese I disappointed by confessing that I was not the legendary Gunness. Being anonymous was everything in those days. Journalists in the country at that time usually had as little to do with each other as possible.

The first serious demonstration in Rangoon actually occurred early on the afternoon of August 3. It took me completely by surprise as it swept down Shwedagon Pagoda Road towards the city center and then turned east going past Sule Pagoda and City Hall, before sweeping around to roar back past the Indian and US embassies—the world’s largest and most powerful democracies, respectively.

As a display of raw courage it was spine-tingling, but pretty difficult to photograph. Demonstrators were initially not keen about having their pictures taken. They covered their faces and sometimes pushed my camera away. An Australian diplomat with a camera was threatened with having his car set on fire, and some Burmese photographers suspected of working for military intelligence were beaten up. Even so, there were no security forces in sight and no attempt was made to stop the demonstration, which faded into the wet afternoon with astonishing speed.

That night, however, the junta declared martial law. The next day troops with colored bandanas, fixed bayonets and shotguns were out on the streets in force. I had no idea what would actually transpire on 8/8/88, but I suspected that if there was to be confrontation it would be in the vicinity of Sule Pagoda and City Hall.

I was staying at my favorite haunt, The Strand Hotel, and I began making arrangements to move to a guesthouse near the old Burma Tourist office. It was incredibly dingy, but it had a grand view over the road encircling the pagoda, Maha Bandoola Park and City Hall.

It was indeed in this area that the first shootings on 8/8/88 took place. A crowd that had been allowed to demonstrate peacefully all day refused to disperse, and troops opened fire.

However, I was not there to see it. I had already been ordered out of the country by my editors who were fearful that they would have no first-hand material to print from the first week of August if I remained. I very reluctantly left on August 6, but not without an official inquisition at Mingaladon Airport about the quantity of film and cameras I was carrying. As I left, I spotted my replacement and two other friends pushing their way through the blue cheroot fumes and chaos in the arrival area. The photographer in the group was arrested on August 9 and deported.

I spent a frustrating time back in Bangkok, gathering photos and accounts of the drama unfolding in Burma without any obvious sign of a resolution. An estimated 3,000 civilians were killed and many more wounded in the aftermath of 8/8/88.

Outraged diplomats had dispensed what little medicine they could find, while hospitals were left virtually empty, particularly upcountry. Many injured people believed it was safer to stay out of sight at home, even with life-threatening wounds.

Opposition leaders, including Aung San Suu Kyi, Tin Oo, Aung Gyi, U Nu and student leader Min Ko Naing, had emerged but they were not a cohesive group. There was nothing remotely credible to replace the lame-duck, temporary government of Dr. Maung Maung, a once respected lawyer and intellectual who had become Ne Win’s hagiographer.

By the second week of September, it was clear that the unending demonstrations were going nowhere. The military was biding its time, waiting to strike back decisively. One of the very few foreign journalists in the country departed on September 17 completely unaware of the imminent coup that was to follow.

When I finally managed to fly back to Rangoon a few days after the bloody September 18 coup, the city was in shock.

I spent the next fortnight getting to know as many of the key players as possible. I tried to piece together the incomplete political jigsaw puzzle. The city was broken and dark, with a curfew still in place. There were military roadblocks everywhere and rebellious suburbs such as North and South Okkalapa were locked down and unreachable.

On October 1, I was back at Sule Pagoda. A dozen or so Hino army trucks had pulled up near City Hall and disgorged troops from the 22nd Light Infantry Division. They had been standing at attention all morning in the blazing sun with bayonets locked. An officer with a large bowie knife strapped to his thigh sat on a park wall behind them. The show of implied force was intended to signal the end of the lingering general strike—and it succeeded.

Nothing moved on the streets, and it was impossible not to be seen. I had a good view of the scene from inside the pagoda’s portico. In the background, a Christian church was pockmarked with bullet holes. I remember reaching into my bag for my camera. Immediately, figures darted from the shadows and challenged me. Burma’s ubiquitous spy network had resurrected itself. I gathered up my bag and walked out behind the ranks of troops in their baking steel helmets and past the officer sitting silently in the shade. Something told me that a chat and a smoke weren’t in the cards.

I overstayed my visa by a full week. Being one of the few foreigners in the country at the time, it was reasonable to assume I had been identified as a journalist but no one made a move against me. I was even able to meet and interview the elusive student leader Min Ko Naing in a suburban safe house on my last day. At the airport, I received a token fine, tipped the immigration officer US $10 for his civility and left.

The overstay was well worth it. I had filed a constant stream of reports to Asiaweek—which ran an astonishing 12 consecutive Burma covers during this tumultuous period. Once outside the country, I continued filing exclusive reports and interviews with all the key opposition figures.

In my last days, I had also made contact with the newly formed Election Commission. It was that first, tentative encounter with a government organization that encouraged me to apply for an interview with Sen-Gen Saw Maung, the chairman of the State Law and Order Restoration Council.

The interview was eventually granted in January 1989, and it was a strange experience indeed. I returned with an official visa. I was met by a military intelligence officer, whisked through formalities, assigned a 24-hour minder and chauffeured off to The Strand.

Ohn Gyaw, the de facto foreign minister, was waiting to greet me in the lobby, which had just been repainted but still showed considerable signs of dilapidation. He briefed me on the senior general’s sense of humor and strong sense of family. Upstairs, Col Thein Swe, a senior aide to intelligence chief Lt-Gen Khin Nyunt, was waiting to continue my briefing. He had evidently been reading my secret file.

“You seem to like our country,” he said. “Is this your second or third visit?”

“Thirteenth, actually,” I said.

He looked stunned. In the land of numerology, it turned out to be my lucky number.