As the train pulled into La Mine station, we rushed to help our fellow passengers with their goods and vegetables. We wanted to assist these new friends we had just made on our trip — and we wanted to look a little less conspicuous.

As we climbed down off the top of the carriage — it was the first time I had ridden on the roof of a train — we descended into a chaotic situation. “Stay away from police and soldiers,” a colleague warned.

The country was sinking into a black hole. The military had staged a coup just three days before, on Sept. 18, 1988.

The police and soldiers who guarded the railway station, however, didn’t recognize us as fleeing students and activists.

I saw many familiar faces on the train. They were making the same journey — to Mon State in southern Myanmar. I nodded to acknowledge them, but we didn’t talk.

There were perhaps hundreds of such people on the train, all heading to the jungle and the legendary Three Pagoda Pass on the Thai border where Mon insurgents had their headquarters.

In my group, there were 10 of us, and we quickly separated as we took horse carts to a nearby village where Mon rebels were waiting to take us to their base.

We were now in a grey zone that was controlled interchangeably by government soldiers and rebels. As night fell we had simple dishes and tried to sleep without blankets as a Mon village headman looked on.

The train ride was the last mechanized transportation we would experience in Burma.

The next day we were on foot and starting on our trek through the jungle.

Our guide was a senior Mon officer. With his AK-47 he often pointed out landmines and places where Burmese troops could ambush us as he led us into the dense forest, over mountains, and across rivers.

Left behind in Yangon were the wounded and the deserted streets where millions had marched just a week before to denounce the socialist regime and were many had been gunned down. Also, still in Yangon was the unwavering spirit of 8888, as well as fearful family members and our friends in the underground movement.

I had naively thought my journey would be a short one and I imagined I would return home soon.

I didn’t know that I would not be able to come back for 24 years. Was it worth it? I would say yes.

The jungle jaunt ended up taking 10 days. It was exhausting but also eye-opening for all of us as we had never been to the ethnic areas where a civil war had raged for decades. We saw deserted villages along the way but also many smiles and abundant hospitality. The Mon villagers had learned about us on BBC Radio and they knew we were coming. How much do you know about our struggle, was a question the Mon rebel leaders asked us repeatedly, They wanted to know how much urban activists and students understood about the long fight of the ethnic minorities.

Jungle life was harsh but in the ethnic rebels who were fighting to gain autonomy we found true friends. Some of the rebel leaders were no strangers to us as they had studied in Yangon University before joining the cause. So they knew our professors and our well-read dissident colleagues who taught us history, politics, literature and about the underground movement.

We also learned some unpleasant things. As we arrived in Three Pagodas Pass the once bursting border trading town was deserted as Mon and Karen rebels had engaged in a fierce battle at the same time as we were marching on the streets of Yangon in August and September. The huts and houses abandoned by villagers became our shelters.

At this point, some of our colleagues were forced to go back to Yangon after becoming caught in a life and death battle with malaria on the Thai-Myanmar border or just because of the harsh life. From our original group of 10, only three of us remained.

After leaving Three Pagodas Pass and doing odd jobs along the border, I decided to set up a publication to inform the international community about what was happening in my country and along the border. Some colleagues joined the armed struggle, went to resettle in third countries to further their studies or continued to fight in the exile movement and became campaign activists or Burma scholars. I wanted to do something to help the cause.

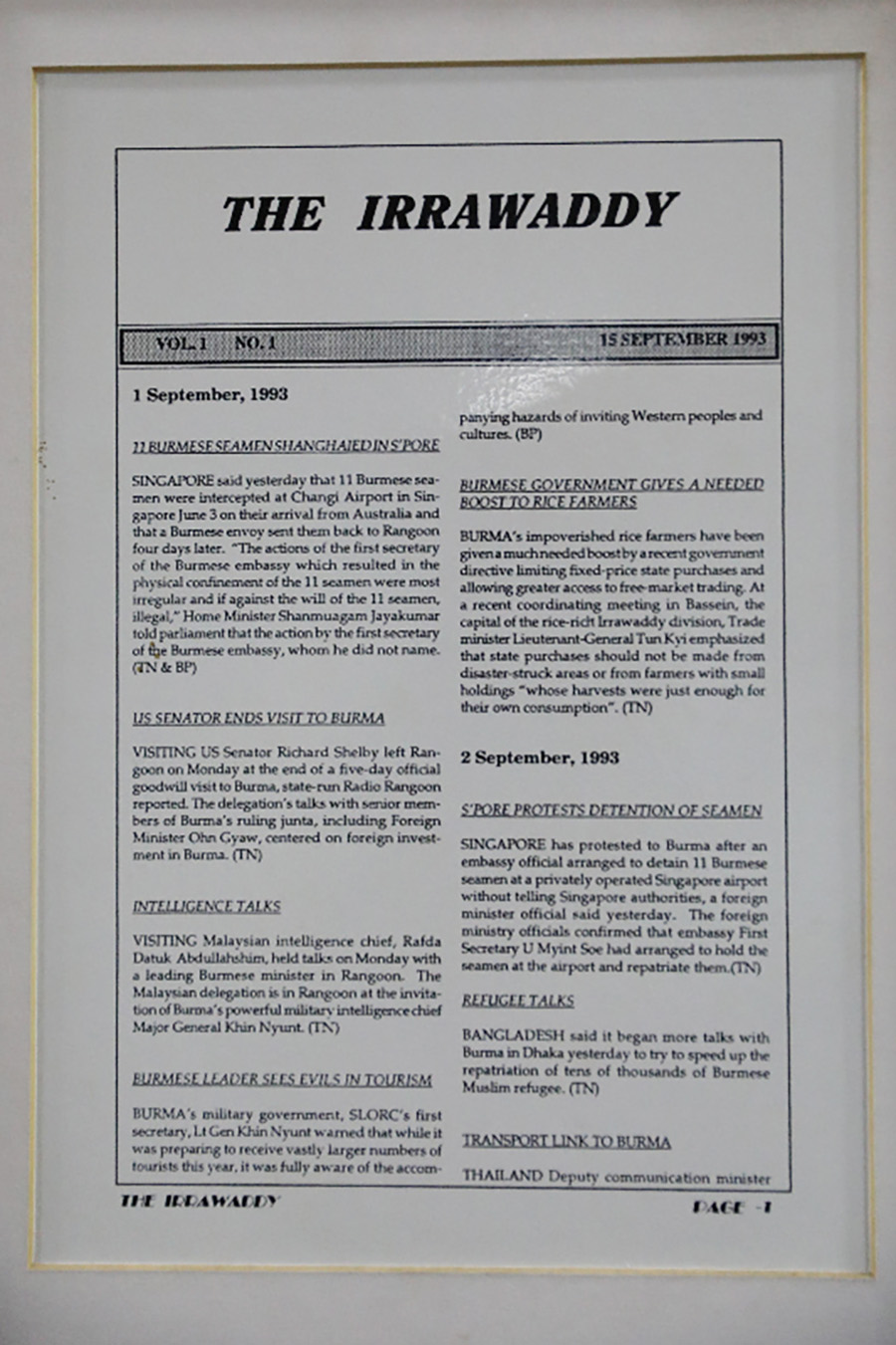

Established in 1993, it is safe to say The Irrawaddy had a direct connection to the 1988 upheaval — its aim was to keep news about Burma alive, and to inform the international community, under the leadership of someone who was in the movement.

But as an independent publication we had to be impartial and to adhere to journalistic standards and not to be a mouthpiece of anyone. We wanted to make sure Burma, and later “Myanmar”, stayed on the international agenda. But we ourselves were in a hideout somewhere in Bangkok. Somehow, we managed to do it.

There were many important world events, milestones and catastrophes including 9/11 in those early years, and the Myanmar issue was often pushed to the backburner. It thus became even more important to remind the world about those under house arrest or in prison or the plight of refugees along the border. We managed to highlight these stories and to tell the busy world of powerful leaders to take note of Myanmar. Top of our minds was to maintain the momentum, and we did it.

One thing I found about my 1988 friends was many were truly willing to make deep sacrifices rather than take advantage of an opportunity either in prison or in exile.

It’s true that we worship those who made sacrifices but we also despise the opportunists.

Aside from the spirit of 8888, there was no shortage of able and competent friends who were always ready to provide assistance. It was in exile that I found my old mate and a 1988 student activist Ko Win Thu, who joined the publication in 1994 and who helped me with the management side of the magazine. Not surprisingly, he is still working with us today.

Established in 1993 we eventually became one of the most recognized publications on Myanmar. Dodging spies and informers in Bangkok – we also became an enemy of the regime.

I still remembered one time the now-defunct Hong Kong-based publication Far Eastern Economic Review referred to us as an “underground dissident publication”. It was true.

At the time, we were always under budget and when we began the mission, all of us were volunteers and we shared a tiny stipend.

The publication was always under the watchful eye of the junta via its agents at the Myanmar embassy in Bangkok and its shady allies. Yes, we have had friends and foes — as always, it is the nature of media. But being an exiled media was tough.

Yet that did not stop us scoring many prominent interviews and publishing opinion pieces from major figures.

Among the many people we interviewed was the late Czech president Vaclav Havel, a staunch Burma supporter, US President Barack Obama, Aung San Suu Kyi, Desmond Tutu and leaders of the ethnic groups, while many more prominent politicians in Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia, and the Philippines spoke to us, lending us their voices to keep the pressure on the regime. Like other exiled media groups DVB and Mizzima, we served as a window on Burma in the 25 years that followed our founding. Our news, interviews, quotes and comments have been published in the New York Times, Washington Post, The Guardian and many other renowned newspapers and magazines from around the world. It was all about Burma and the continuation of an unfinished struggle.

Last week when I glimpsed at old files and Irrawaddy issues I noted the long list of veteran regional journalists such as Bertil Lintner, Kavi Chongkittavorn, Thitinan Pongsudhirak, Don Pathan, Dominic Faulder, and John McBeth who have contributed numerous op-ed pieces and analyses. Young Burma researchers who penned articles in our publications have now become recognized voices and independent analysts on the country. After all, we were one of the few credible and reliable, independent voices covering Myanmar.

When I decided to leave Burma I did so with no hesitation, thinking I would be back soon. But it took 24 years, or over 8,000 days, before I could return to my home country. Without resilience, determination and support it would have been difficult to keep that walk going for 30 years.

It was naïve to think and imagine that when we finally got the chance to return we would find a free and perfect Burma. To be sure, it is not the case. Indeed, it is more like the opposite. Even bringing our institution back to the country was tough and the last six years we have gone through a mountain of challenges and uncertainty, similar to what’s faced by many in the country. It is true to say that the uprising failed, was exploited, and the dream of 1988 remains elusive. The intense search to find hope and justice is not getting any easier but we, along with many others, are not giving in. It is clear we will have to navigate large waves in our journey.

We will not give up on reporting about Myanmar and will not give up spreading hope to millions of people who deserve more than they have received, and we are continuing to hold our place as an important part of Myanmar’s besieged fourth pillar.

This means the old spirits of 8888 and their voices are needed more than ever.