For Thida Win, the trip home from her farm has been a daily torture since September last year: she knows the boy who used to welcome her will not be there. She can no longer bear the sound of children reciting their lessons at the village school as she misses her seven-year-old son, Phone Tayza, terribly.

She is not alone.

Whenever it rains, especially in September, tears well in Daw Nu’s eyes when she thinks of her youngest son, Zin Ko Oo.

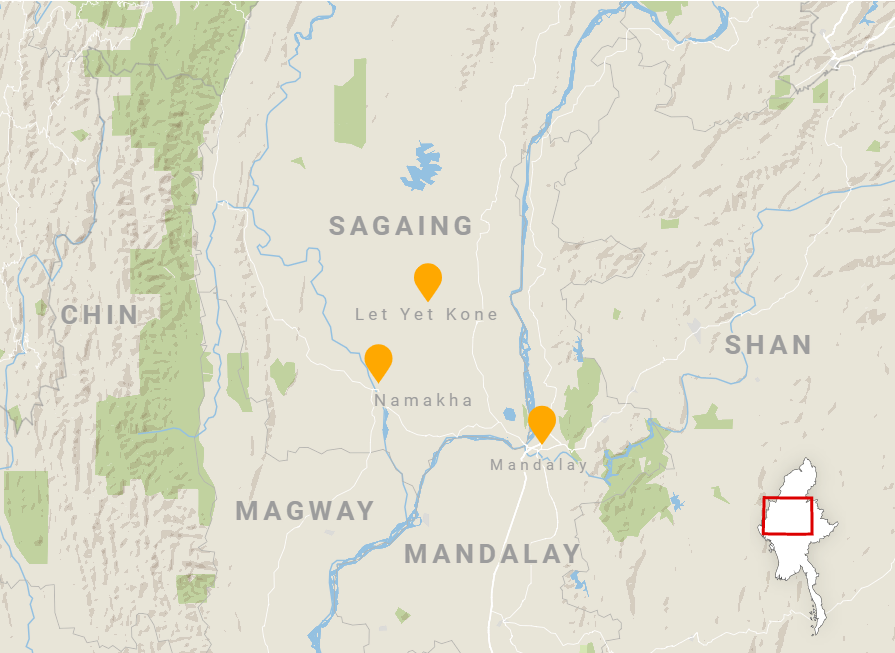

Phone Tayza and Zin Ko Oo were aamong the seven children – the youngest aged just seven – killed by a Myanmar regime airstrike on Let Yet Kone village school on September 16 a year ago. The attack killed 13 people in total.

It began when two Mi-35 helicopter gunships swooped down and opened fire on the school, where about 200 young students were attending classes. Infantry troops then attacked on the ground.

The junta said its troops raided the village because resistance forces were planning to transport weapons via Leyt Yet Kone. Villagers denied that claim.

The regime’s massacre at the school shocked the nation and the world. The UN Secretary General strongly condemned the attack, calling the deaths an example of one of the “six grave violations” against children in times of armed conflict strongly condemned by the UN Security Council.

As the anniversary of the attack looms on Saturday, villagers are still haunted by the events of that fateful day.

“Although it has been a year, we the residents of Let Yet Kone can never forget this most cruel act of the military,” said Daw Moe Moe, the village schoolteacher.

“Our traumas will never disappear as long as we are alive,” she added.

Mothers’ tears and trauma

Whenever it rains heavily, Daw Nu thinks about her youngest son, Zin Ko Oo,14, who lost his life in the airstrike.

Among her five children, Zin Ko Oo was the youngest and “the clever one”. The 55-year-old mother said her son studied hard and won prizes at school.

“I ask myself every time it rains: Where is my son?” said Daw Nu, her voice cracking and trembling with emotion.

Like Daw Nu, Thida Win sobs every time she returns home from her fields, knowing her younger son won’t be there to welcome her.

“He always waited and welcomed me when I returned home from the farm. As the days go by, I miss my son more and more,” Thida Win told The Irrawaddy through her tears.

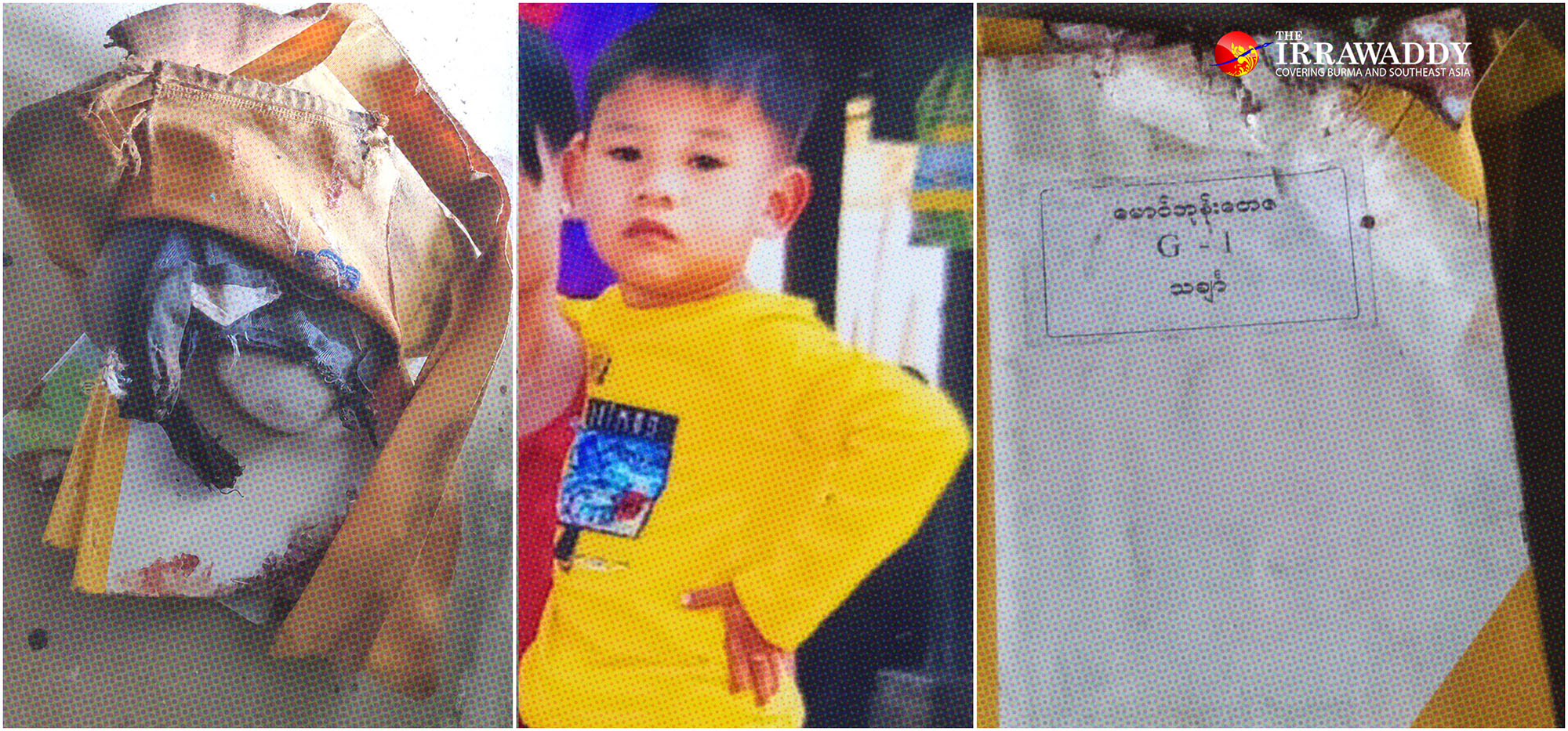

Phone Tayza, 7, was in class when the junta helicopters leveled their guns on the school and opened fire.

After they killed her son, she moved from her house by the school because it broke her heart to hear the sound of children studying. She has avoided the school since the airstrike.

Maimed schoolkids

Like the mothers who lost children, those injured in the attack are also trying hard to recover and resume their normal lives. Seven children were wounded in the massacre.

Chaw Chaw, 13, has trouble walking after her leg was shattered by regime weaponry a year ago.

“One of her legs will never recover,” said Aye Chan Moe, an 11-year-old student and eyewitness to the deadly airstrike.

Aye Chan Moe recalled watching as the blood seeped from Chaw Chaw’s leg wound and stained her body.

Eight-year-old Phyo Maung Maung was hit in the eye during the attack. Despite undergoing long treatment costing hundreds of thousands of kyats, he never fully recovered his vision. Likewise, the hand of his schoolmate, 10-year-old Su Su, remains deformed after being shredded by junta weaponry.

Aye Chan Moe said she sometimes cries when she sees her injured friends.

“I am angry with them [soldiers]. I want to kill,” she told The Irrawaddy.

The massacre has also left the schoolkids with deep mental scars that will not heal.

“I am afraid whenever planes fly over,” nine-year-old Lin Lin told The Irrawaddy.

Indiscriminate campaign against civilians

The Let Yet Kone airstrike is among the worst aerial massacres perpetrated around the country by the regime since the coup in 2021.

Myanmar Witness, an NGO reporting human rights violations in Myanmar, was able to geolocate footage and images showing extensive damage to the school in Let Yet Kone. Its report said that video, images and reports by villagers were proof of a bloody attack on the school and monastery.

The report said the regime used S-5 rockets during the attack, citing evidence of casings and debris at the scene.

“The S-5 rocket can only be fired by compatible fighter helicopters and jets which are used mainly for ground area targets,” Myanmar Witness said, adding that the regime’s air force is the only known entity in Myanmar with aircraft suitable for S-5 rocket use.

In October 2022, three regime warplanes launched a strike on a music concert being held to mark the Kachin Independence Organization’s 62nd anniversary at a village near Hpakant, Kachin State, killing nearly at least 75 people.

Five months later, 157 civilians including 30 children were killed by a regime aerial bombardment in Kantbalu Township’s Pazigyi village on April 11 this year. It marked the worst massacre perpetrated so far by the regime.

The attacks were condemned internationally and domestically as part and parcel of the regime’s indiscriminate campaign against civilians in response to the nationwide armed resistance. The junta had carried out 1,427 airstrikes across the country as of April this year, killing 634 civilians since April 2021, according to a report by Nyan Lynn Thit Analytica, a non-profit political research organization.

Children account for a high proportion of the fatalities in the regime’s attacks, including airstrikes.

According to the civilian National Unity Government (NUG)’s Ministry of Women, Youth and Children Affairs, a total of 414 children across the country had been killed by regime airstrikes and artillery as of May 24 this year. Areas under attack include anti-regime strongholds like Kachin, Kayah, and Karen states and Magwe and Sagaing regions.

Villagers still living in fear

Although there have been no more airstrikes on Let Yet Kone since late last September, regime forces continue to conduct frequent shelling and infantry raids to terrorize villagers across the township.

Since the massacre, the village has been torched twice by regime soldiers, in December and January. The arson attacks incinerated around 230 of the 300 houses in Let Yet Kone. Meanwhile, the villagers live under constant threat of shelling by regime troops stationed in neighboring Ye-U and Depayin townships.

“Our village exists between the two townships, so we just live in fear,” Daw Nu muttered.

The villagers say they have fled their homes more than 20 times over the past year due to regime raids in the township.

“There has not been even one month when we could live free of anxiety,” Thida Win told The Irrawaddy.

The displaced villagers currently live in huts built on donations from home and abroad but are constantly ready to flee amid the frequent junta raids, said Daw Moe Moe.

Following the massacre, Let Yet Kone residents worked to reopen the school in a show of defiance against junta brutality and because they wanted education for their children. The school was reopened just a month after the airstrike and is currently attended by 232 students.

“The education and learning festival was held on September 6. Parents and teachers cried at the event because they missed the victims of the attack last September,” said Daw Moe Moe.

‘Not leaving’

Despite the ongoing terror campaign being conducted by regime troops in the region, Let Yet Kone’s remaining residents insist they won’t quit their village.

“It is not safe anywhere in our country. So, we refuse to consider leaving the village where we were born,” Daw Moe Moe explained.

She also called on the civilian National Unity Government to increase efforts to root out the military regime.

“For generations, we will never forgive military dictator Min Aung Hlaing,” she told The Irrawaddy.

Thida Win said she doesn’t want to see any more mothers suffer the same fate as her by losing their children.

“I don’t want to hear any more news about children being killed,” she said.

She wants the revolution to succeed as soon as possible so she can return to living a peaceful life.

Daw Nu wants to see children attend the village school free from the fear of regime raids, airstrikes and shelling.

“If Min Aung Hlaing dies quickly, we will be freed from all this trouble,” she said.