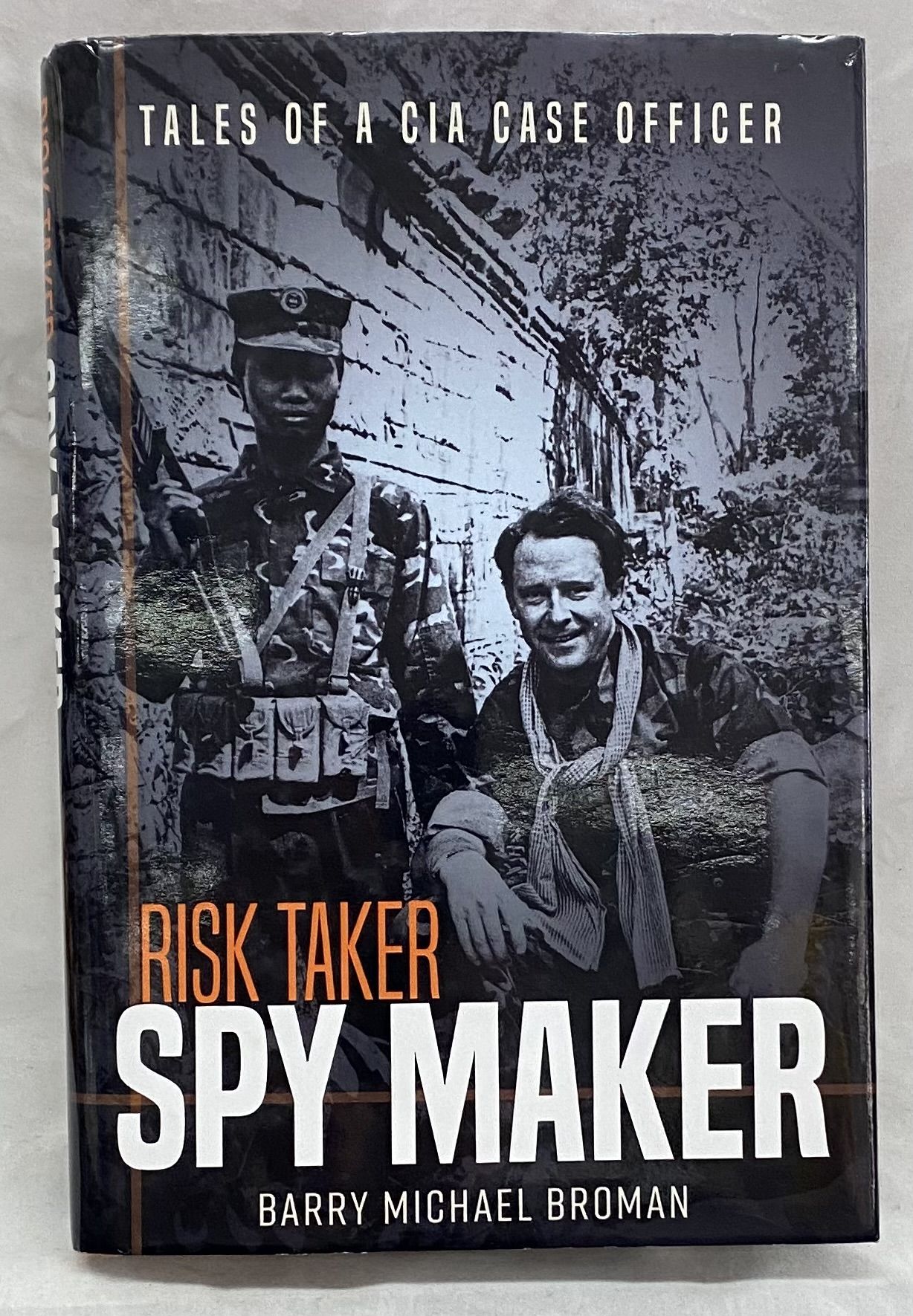

Risk Taker, Spy Maker: Tales of a CIA Case Officer by Barry M. Broman, Casemate Publishers, US$34.95.

Back in the late 1980s, the General Accounting Office (GAO), a US government agency that monitors whether federal funds are being spent efficiently and effectively, carried out a thorough investigation of Washington’s assistance to Myanmar’s drug suppression program. GAO, now known as the General Accountability Office, concluded in a report dated September 1989 and titled “Drug Control: Enforcement Efforts in Burma Are Not Effective” that “eradication and enforcement are unlikely to significantly reduce Burma’s opium production unless they are combined with economic development in the growing regions and the political settlement of Burma’s ethnic insurgencies.”

Barry Broman, who served as the Yangon station chief of the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the 1990s, presents in his book Risk Taker, Spy Maker: Tales of a CIA Case Officer an entirely different version of the Myanmar military’s alleged anti-narcotics program: “In the 1980s, the State Department ran a very successful counter-narcotics program in Burma, considered by many to be the best of its type in the world. In addition to training in the US and assistance on the ground sharing intelligence, the US provided helicopters to assist operations against the druglords in the north.”

Broman, a supposedly experienced intelligence officer, is either ignorant of the realities on the ground, or he is—for whatever reason—deliberately covering up the Myanmar military’s involvement in the drug trade. Active Myanmar army cooperation with the drug lords began in the 1960s, when the then dictator General Ne Win authorized the formation of local militia units called Ka Kwe Ye (literally “defense”), or KKY, which would fight against ethnic and political rebels in areas which the government’s forces had difficulty in reaching. But the military government did not have enough money in its coffers to support such a sustained counterinsurgency program, so in order to be self-supporting the various KKY units were allowed to use all government-controlled towns and roads for opium trading.

It is often forgotten that notorious Golden Triangle drug lords such as Lo Hsing-han and Zhang Qifu (alias Khun Sa) began their respective careers and amassed their initial wealth as government-allied militia commanders. Lo commanded the local KKY force in his home area Kokang, and Zhang was the head of the KKY in Loi Maw, an opium mountain in northeastern Shan State. Lo’s Kokang KKY fought actively together with government forces in the battle against the then powerful Communist Party of Burma (CPB) at the Kunlong bridge on the Salween River. That fight lasted from the end of November 1971 to January 1972 and the government’s forces would not have been able to win that fight without the assistance of Lo’s men, who were familiar with the local terrain. When the battle was over, grateful Myanmar army units even helped protect Lo’s mule convoys, which carried opium down to the Thai border.

Zhang had several prominent Shan rebel leaders assassinated—and decided to go underground and proclaim himself a “Shan freedom fighter.” In January 1996, he struck a deal with the military government in Yangon, disbanded his 15,000-strong private army and moved with his family—and money—to Yangon. Lo was arrested in 1973, not for narcotics trafficking, which he had been permitted to engage in, but for “rebellion against the state”. He had in 1973 formed a brief alliance with the rebel Shan State Army (SSA), and on that charge he was sentenced to death. But he was pardoned and released during a general amnesty in 1980 and was allowed to form a new armed force, now under a new counterinsurgency program called Pyi Thu Sit, or “people’s militias”. He and his family also set up a company called Asia World, which became one of Myanmar’s wealthiest and most influential conglomerates.

The Myanmar drug trade has always been carried out locally by such militia forces, and still is today. As Broman says in his book, the US did provide the Myanmar military with helicopters—but those were never used “in operations against the druglords in the north.” They were deployed in general counterinsurgency campaigns and, in one instance in late 1985, to chase me when I, my family and our ethnic Kachin escorts trekked through rebel-held areas in northern Myanmar.

Broman makes the remarkable claim that “after US assistance ended in 1988, drug production rose tenfold.” But the benevolent Myanmar military nevertheless “continued to cooperate with the DEA [the US Drug Enforcement Administration] and CIA.” Broman writes that he “directed the American team on one of those operations in 1995.” Broman should have checked his figures before putting anything as misleading as that in print. It is correct that Myanmar’s opium production did increase in the 1980s, but it was certainly not “tenfold”—and that had nothing to do with the US ending its support for the Myanmar Army’s campaigns in the frontier areas.

When I first wrote about the Golden Triangle drug trade in the early 1980s, general estimates of Myanmar’s opium production were in the order of 350-400 tons annually. It began to rise in the mid-1980s, mainly because narcotics became a valuable commodity following a near-collapse of the Myanmar economy. The 1987 harvest yielded 836 tons of raw opium and, by 1995, production had increased to 2,340 tons. Satellite imagery showed that the area under poppy cultivation increased from 92,300 hectares in 1987 to 142,700 in 1989 and 154,000 in 1995. The potential heroin output soared from 54 tons in 1987 to 166 tons in 1995, making drugs the impoverished and mismanaged country’s only growth industry. At the same time, a string of new refineries was set up in Kokang and the Wa hills, conveniently located near the main growing areas in northern Myanmar and, equally important, close to the then new and rapidly growing Chinese drug market and seemingly easier routes through Yunnan to the outside world. And all that was made possible because of a mutiny among the hilltribe rank-and-file of the CPB’s army in 1989. The mutineers entered into ceasefire agreements with the Myanmar military, and in exchange, were allowed to engage in any kind of business.

Broman also fails to mention that a US-financed program actually contributed to the increase in opium production in the 1980s. The US had decided to pay for the chemical 2,4-D to be sprayed over opium fields otherwise inaccessible to the government in Yangon. But instead of curbing production, the program only encouraged poppy farmers to increase their planting in the hope of compensating for expected spraying losses. “We sprayed them into overproduction,” a narcotics expert in Bangkok told me after the program and all other US assistance to Myanmar was suspended following massacres of pro-democracy demonstrators in August and September 1988. Broman’s version of events is that “the State Department considered Burma to be a pariah state after the regime put down pro-democracy protests in 1988.” Relations between Myanmar and the United States became “poor” over “human rights and democracy issues.” Full stop.

“Put down pro-democracy protests”? Admittedly, Broman mentions, but only in passing, that the crackdown was “bloody”, but fails to write that the very same military clique he cooperated with as CIA station chief was responsible for gunning down about 3,000—yes, 3,000—protesters in 1988. Troops sprayed automatic rifle fire into crowds of unarmed demonstrators, and thousands more were arrested and badly tortured in the Myanmar military’s detention centers.

Broman’s appalling account of events in Myanmar in the 1980s and 1990s becomes easier to understand when taking into account that he returned to the scene after his retirement from the CIA—now to help improve the then ruling junta’s abysmal image in the international press. The Irrawaddy reported in June 2003: “In June 2002, Broman took a position with the Washington-based lobbying firm DCI Associates, which inked a US$450,000 annual contract with the Burmese regime last April.” However, “the firm failed to sway policymakers regarding the junta’s sincerity on narcotics matters, and in January 2003 the US refused to certify Burma as a nation in compliance with drug control efforts. The DCI contract was canceled by the regime after the decision, but Broman has continued to lobby the international media on behalf of military leaders in [Yangon].” Broman never refuted The Irrawaddy’s report.

But Broman is not alone. The DEA has also had local agents in Yangon who seem to have operated on their own authority. As I wrote in The Irrawaddy on May 5, 2022, it had been discovered that a Yangon-based DEA officer, Angelo Saladino, had authored a secret memorandum dated March 15, 1991 and addressed to Myanmar’s then intelligence chief, Major General Khin Nyunt. The memorandum, which had an official DEA letterhead, was leaked and made public. Saladino listed various ways that the military might try to impress the US government as well as United Nations agencies. He also provided specific suggestions on ways to “deprive many of Myanmar’s most vocal critics of some of their shopworn, yet effective weapons in the campaign to discredit [Myanmar’s] narcotics program.” Finally, Saladino recommended several options to the junta for silencing “its most biased critics.”

Saladino flew back to the DEA’s headquarters in the US when the scandal broke and managed to convince his superiors that he had not, after all, sent the memorandum to Khin Nyunt. A compromise was reached with the State Department: Saladino had his tour of duty in Myanmar officially curtailed but was allowed to serve out his term, which only had a few more months to run.

On the other hand, a DEA analyst who blew the whistle and said that they were actually cooperating with the very people who were behind the Golden Triangle drug trade was transferred out of Myanmar and given a post somewhere in the United States. A Southeast Asian source, not this analyst, commented way back in the 1980s: “The DEA earns its budget by making poor [hilltribe] farmers seem guilty, and otherwise doing nothing except occasionally bust some careless scavenger. In this way, the DEA ironically ends up serving only to police the narcotics trade for the greater benefit of the drug kingpins.”

Official US policy towards Myanmar has always been abundantly clear. Since 1988, successive governments in Washington have expressed their support for the struggle for democracy in Myanmar and issued statements condemning human rights abuses perpetrated by the Myanmar military. But it is evident that official policy time and again has been undermined by some rogue agents in the field. Broman’s book is testament to that fact, and it should therefore be read by everyone who wants to understand why American approaches to the situation in Myanmar—be it drugs or human rights—sometimes may seem confusing and contradictory.