LOIKAW, KAYAH STATE – Ethnic language teachers prefer curriculums based on their own languages to textbooks translated from Burmese, educators in Loikaw, Kayah State told The Irrawaddy.

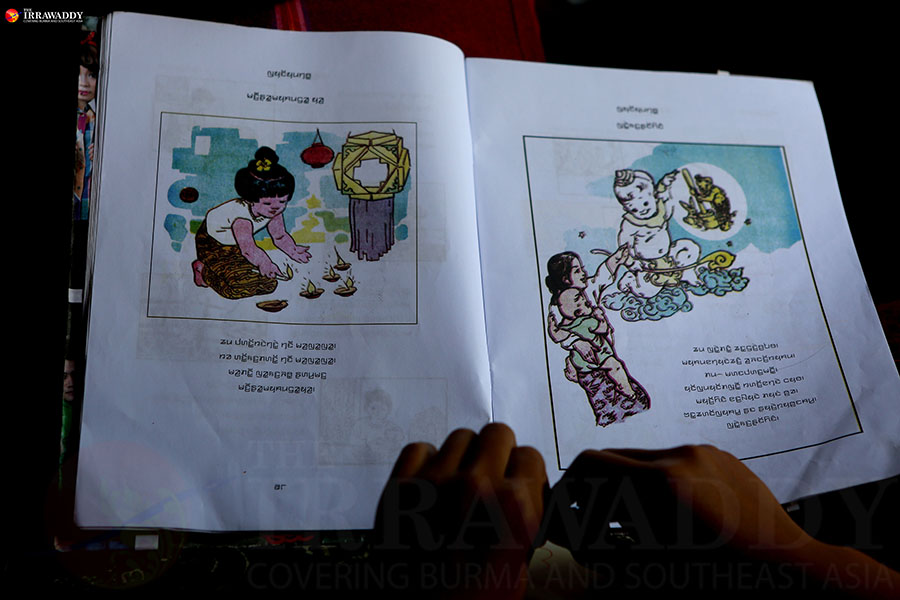

The former quasi-civilian government allowed in 2012 for ethnic languages to be taught as extracurricular subjects in locations with a majority of non-Burman students. Yet the curriculums utilized were and continue to be versions of the original Burmese primary textbooks into those ethnic languages.

In Kayah State, around 120 out of 150 schools teach their own ethnic languages from grades one to three, while Burmese remains the language of the curriculum thereafter.

Four ethnic languages—Kayah, Kayan, Kayaw and Gaybar—are being taught at the moment to some 10,000 students with over 330 teachers across the state, according to Kayah State’s education department. Gaybar language instruction was only added this year, at the first grade level. Other Karenni ethnicities—including Yin Baw, Yintalay, Gaykho and Manu Manaw—have no classes yet.

“Translating Bamar textbooks into the ethnic languages only allows for about 30 percent understanding by the students, as they can make guesses from the pictures. But the text is hard,” said Maw Hsu Myar, deputy director at the Kayah State education department, who is responsible for ethnic language development.

She said every ethnicity is trying to develop their own curriculums, as translated textbooks “are not effective.” Thus far, the Kayah language curriculum has been developed and a textbook and teachers’ guide is expected to be available in September. But curriculums for other ethnic languages like Kayan, Kayaw and Gaybar still exist only in translated versions.

Teaching Time

Under the current regulations, ethnic nationality languages are taught for one hour per day; in Loikaw, like in many other places in Myanmar, the classes are taught outside of normal school hours.

The No. 3 Basic Education High School in Loikaw teaches the Kayah language classes for about 30 to 45 minutes at lunchtime, after both the students and teachers quickly eat their food.

“As there is not enough time on weekdays—we have to teach them every Saturday for about half a day, from 8 a.m. to noon, for them to be able to catch up with the curriculum,” said Byu Myar Cho, a teacher who is also the Kayah language instructor at the school. She has been teaching Kayah since 2013.

The high school has two classrooms that teach Kayah and Kayaw languages, with 35 students per class.

If it were possible to designate session to teach Kayah language within the class timetable, it “would reduce a lot of the burden” on the students as well as the teachers, Byu Myar Cho explained.

“The ethnic students have neither time to play at the lunch break nor to rest on Saturday, while other students can. It is a burden for us now. We want to teach the Kayah language like other subjects, in the class time,” she said.

The teachers have to use both languages—Kayah or Kayaw and Burmese—to teach the students, because the textbooks are translations.

“The new Kayah curriculum is easier to teach because in Kayah, we also have our own alphabet, consonants and vowels. The students should be taught from an easy level, starting with the basic Kayah alphabet,” Byu Myar Cho said.

It is a “weakness of the policy” that the ethnic languages have to be translated from the Burmese language curriculum, said U Thein Naing, an ethnic language curriculum consultant and curriculum expert. He has been working with the education department for the development of a Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MTE) approach. He is also a curriculum consultant for Mon and Kachin states.

U Thein Naing said the ethnic language policy should be based on MTB-MTE and that the curriculum has to be based on the ethnicity, as well as the locality. The approach recommends that students’ native languages not only be taught as separate subjects, he said, but embraced to teach core curriculum content, like mathematics, social studies, and art.

He urged ethnic nationality educators to participate in drafting new curriculum content and outlined the importance of states carrying out their own research and having the freedom to make decisions to meet their regional needs. “The government needs to acknowledge those efforts to enhance capacity and should support the ethnic education departments,” he said.

Khu Phe Nyoe Reh, chairman of the Kayah National Literature and Culture Committee (KNLCC) said that teaching ethnic languages outside of class time hinders students’ advancement to the next level in that language, despite the fact that they move up to different grades in other subjects.

Even though there have been delays thus far, Khu Phe Nyoe Reh said that he sees the government’s initiatives as a step toward supporting their needs. He hopes that further efforts will be made to teach ethnic nationality languages during regular class hours, to hire more educators, and to provide greater support for appropriate teaching materials.