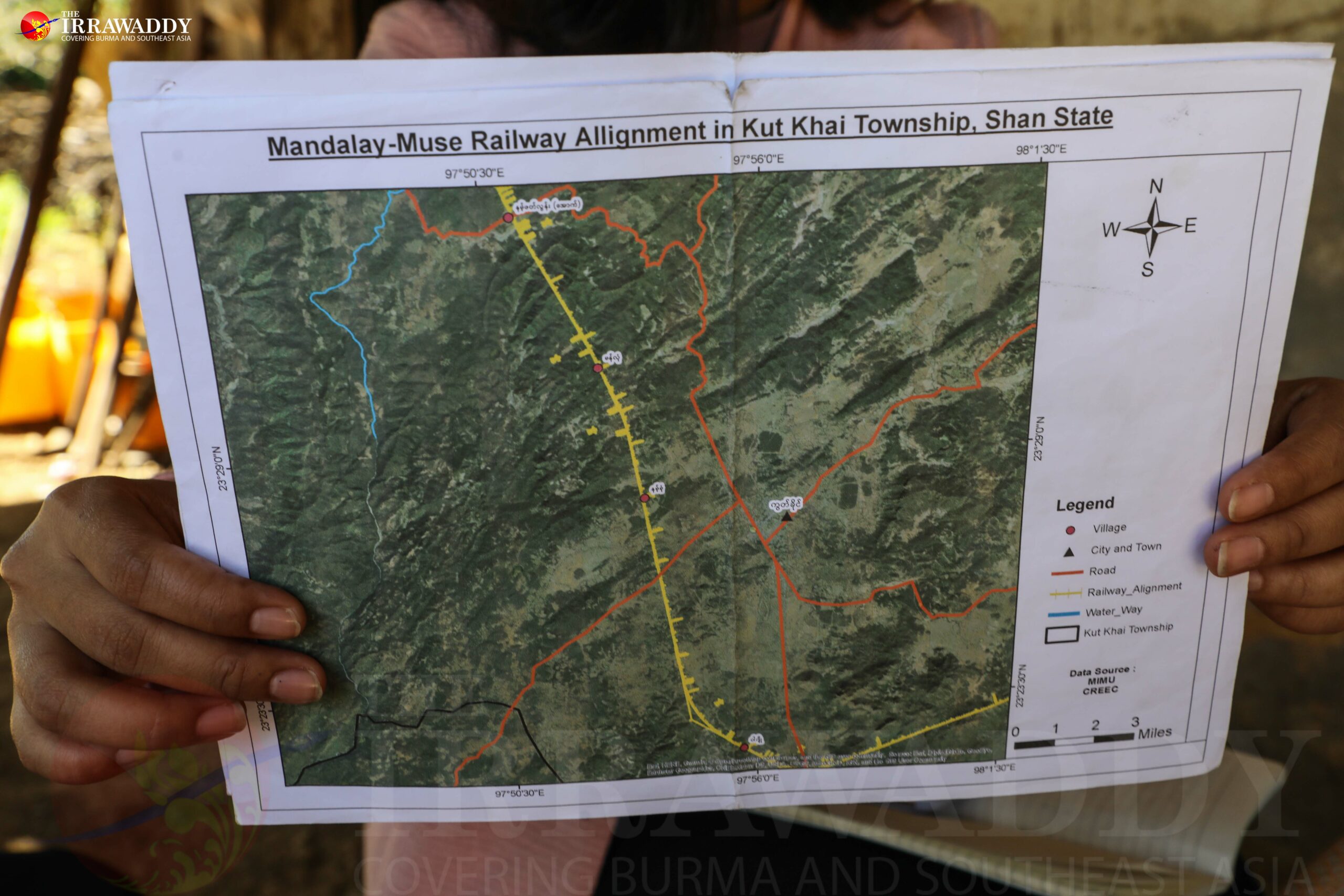

China’s President Xi Jinping was in Myanmar in January hoping to cement ties between the two countries with a raft of agreements, including several massive infrastructure deals. As part of the 33 deals, protocols and exchanges, Xi handed over a feasibility study for a high-speed railway connecting Kyaukphyu port in Rakhine State with Yunnan in southwest China. This study includes a ground survey carried out by officials from Myanmar Railways and China Railway Eryuan Engineering Company in 2019, as well as public forums with residents living along the route, many of whom are worried about the possible loss of their homes and farms, as well as adverse environmental impacts. The Myanmar and Chinese governments signed an MoU for the project in 2018, but the final decision of the Myanmar government over whether to build the railway is still unknown.

If this project came to fruition, it would see a railway built which was first mooted over 150 years ago. This article tells the story of that railway, a story which involves a host of characters from amateur colonial railway fanatics and factory owners in Britain, to Panthay Muslim rebel princes in Yunnan. Using archival materials from the Royal Geographical Society in London and the British Library, as well as books, newspapers and magazines of the time, this post follows the fate of the plans for a railway in the 19th century. The project came close to being realized in the late 19th century, when construction began in 1896 but was soon abandoned. In the end, wider geopolitics—the Great Game in Central Asia and competition with France in Qing China—were what determined the success or failure of these 19th-century plans for a railway.

Explorers and rebels

In the early 19th century, a handful of British explorers and railway enthusiasts first drew attention to the idea of building a railway from Burma to Yunnan. The idea developed so that Britain might ‘tap’ the markets of southwest China, bypassing the Straits of Malacca, thereby reducing journey time from Europe to China.

Burma, still part of British India, was seen as a link between the main markets of China and India. As one explorer put it, “the path between the 250,000,000 inhabitants of India and the 300,000,000 inhabitants of China should be opened to trade.” [1]

Proponents of the railway persuaded various Chambers of Commerce in Britain that surplus production in Britain could be solved by selling more goods to China.[2] The British Chambers of Commerce were enthusiastic supporters of the railway enthusiasts and explorers, and provided their go-to source of expedition funding.

These 19th-century dreams of a railway to Yunnan stemmed from the wider context of colonial exploration and exploitation of continents’ interiors, and in the perceived “scramble for China” at the time. For Western imperial powers towards the end of the 19th century, there was a sense of inevitability regarding the partition of China between European colonial powers, including Britain and France.[3] In 1898, the pro-British government newspaper, The Straits Times, reported that France was “playing her role in China with great skill”, as the Powers staked out territory in China.[4] The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser predicted that China was going to be “smashed up and divided among the powers one of these days”.[5]

The 19th century also saw a global railway-building boom, as continental interiors were connected by the construction of extensive railway networks. The British looked at the transcontinental railways being built by the US and Russia, and worried that rival powers were overtaking them in this race to reach internal markets and natural resources. The first railway line in India—34 kilometers from Bombay to Thana—was built in 1853, and within 20 years, a network of 3,800 km had been created.[6]

One of the best-known amateur railway enthusiasts in 19th-century Burma was Archibald Ross Colquhoun, who spent years proselytizing for the railway. Born at sea off the Cape of Good Hope, Colquhoun’s first job was as an assistant engineer to the Public Works Department in Tenasserim (now Tanintharyi) in 1871. While accompanying an official expedition to northern Siam in 1879, he converted to the idea of a railway, “to which so much of his life and the greater part of his financial resources were to be sacrificed”, as his wife Ethel Colquhoun put it. Basically, he “hoped to best the French in this race for the trade of the rich province of Yunnan”.[7] In 1880, Colquhoun set off on a self-funded trip from Canton to Mandalay, aiming to survey a route for the railway. For Colquhoun, southwest China in the 1880s was a pristine frontier “wilderness”. In his 1883 book about these travels, Across Chryse, he reported that Yunnan was “still practically untouched”.[8] These ideas fit his imperialist worldview—cemented in his later years as a member of Rhodes’s Pioneer Column, the first administrator of Mashonaland (northern Zimbabwe), and in retirement, as a fellow of the Royal Colonial Institute and editor of its journal, United Empire.[9]

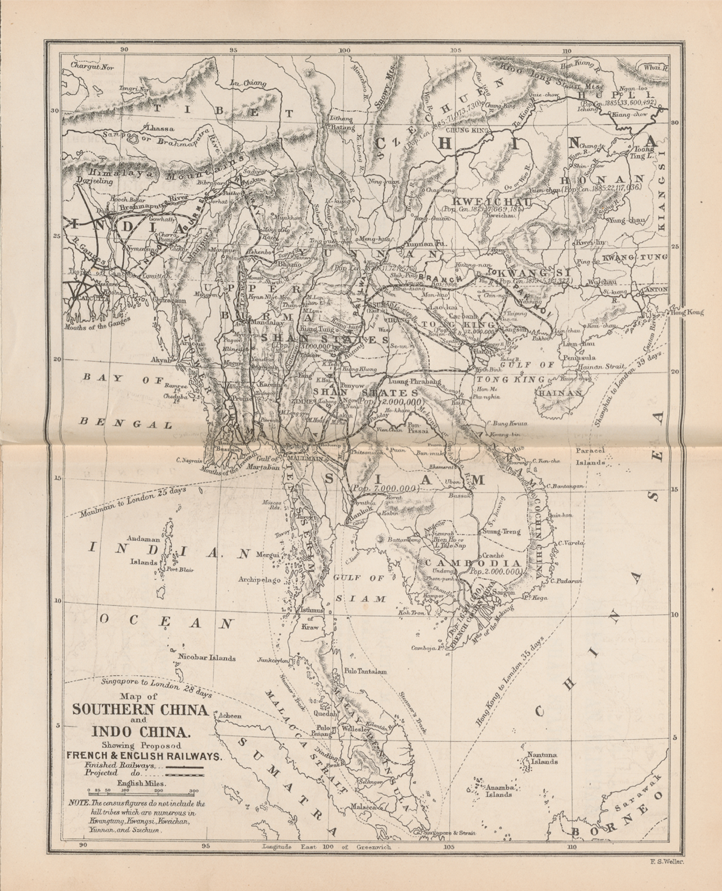

Holt S. Hallett, another vocal proponent of the railway, accompanied Colquhoun on his 1883-84 expeditions. In the map below, from 1890, Hallett envisaged two routes from China to northern Burma. One route ran from Ssumao (today Pu’er) in Yunnan, passing east of Keng Tung and into northern Thailand, eventually splitting to reach Mawlamyine and Bangkok. None of these lines existed in 1890 at the time the map was made. Construction of a railway from Bangkok to Ayutthaya only began in 1890.

The other route began near the Burma-China border at Bhamo and ran due south to Mandalay, from there joining an existing line to Rangoon.

Colquhoun and Hallett were actually late to the game. The idea of a railway to Yunnan had already been entertained, tested and rejected 10 years before they first visited the Shan States. Various schemes had been proposed to the government of India in the 1860s, by “some mercantile gentlemen in Rangoon”, and commercial bodies in the UK.[10] These were all rejected on grounds of cost, however, until Colonel Fytche, Chief Commissioner of Burma, decided to support the idea. Fytche apparently became convinced about the need for a railway when he read about the trade between Upper Burma and Yunnan, which had been cut short since the Panthay Rebellion began in 1857, in Captain Yule’s Narrative of the Mission to Ava.[11] In 1867 Fytche persuaded the government of India to send a survey party to Momein (today Tengchong).

This survey party, led by Colonel Edward Sladen, crossed the Kachin hills from Bhamo to Momein in 1868. Today, Sladen is infamous as the rumored thief of the Burmese King’s Nga Mauk ruby, but at the time, Sladen was merely the British agent at the royal court in Mandalay. His mission to China happened at the high point of the Panthay Rebellion, which had broken out in Dali 10 years before. The same year that Sladen visited, Sultan Suleiman, the leader of the rebellion, marched on and encircled Kunming, Yunnan’s largest city and the last stronghold of Qing Imperial forces in Yunnan.[12]

Sladen’s expedition spent two and a half months in 1868 stuck in a village in the Kachin hills while a dacoit leader, Leeseetahee, refused to let them pass. The Panthays then sent a military escort to accompany them through the passes which the dacoits controlled. When they arrived in Momein, the Panthay Governor, Ta Sa Kone, came out to welcome Sladen to his capital. Panthay officers in uniform, standard bearers, and flag-waving villagers lined the road into Momein. Sladen described how, “after several months of obstruction and annoyance”, the expedition “suddenly found themselves amongst powerful friends and raised to the position of well-favored guests”.[13]

Sladen’s report focused on the Panthays’ support, but ignored the months he spent trapped by dacoits. Another explorer, Ney Elias, summarized the Sladen Mission as meeting “every kind of obstruction, intrigue, open and covert hostility” from the various nations and tribes concerned, all “in order to thwart the progress of the party”.[14] Sladen’s report, however, stated that their trip “has assured us of the goodwill and hearty cooperation of the several races bordering on Burma”, and that therefore a railway project may be “reasonably entertained and successfully accomplished”.[15] Sladen’s insistence on portraying the expedition in a positive light indicates the depth of his newfound support for the Panthays’ cause.

While in Momein, Sladen encouraged Ta Sa Kone to send a mission to London to seek official support for the Panthays’ rebellion. The Foreign Office and India Office were dismayed when this mission arrived in London without warning in 1872, bearing gifts and seeking an alliance with the British against the Qing. The India Office wrote to Argyll, the Secretary of State for India, that the Panthays’ aims in London were “preposterous” and that the British needed to get rid of them immediately.[16] The Secretary of State for India drafted a letter to the government of India expressing surprise that they could have allowed the mission to continue through Calcutta, as “nothing but embarrassment” could arise from their appearing in London.[17]

The episode reveals a disconnect between the views of the British in Burma on one hand, and in London on the other. Many in Burma proposed allying with the Panthays—perceived as a “martial” race and natural allies—to suppress dacoits and increase trade with China. Policy-makers in London and India, on the other hand, were more cautious about the idea of making war on the Qing and acquiring a vassal state in southwest China.

Sladen, visiting Momein at the high point of the Panthay Rebellion’s success, seemed to have subscribed to a future where the Panthays governed a Muslim state in Yunnan, helping the British to secure trade with Upper Burma. Within a few years of Sladen’s expedition, however, the Panthay Rebellion failed. The colonial government once again deemed the route to Yunnan to be unsafe for travelers and the railway idea was put to rest for another few years.

The ‘Great Game’ and the ‘Scramble for China’

For most of the 19th century, the Burma-Yunnan railway project remained only the dream of a handful of British enthusiasts. Their failure to gain support from the British Government was in part due to wider geopolitics. The “Great Game”—the 19th-century rivalry between Russia and Britain—was the lens through which the British government saw foreign policy in the East, and while they concentrated on Central Asia, they overlooked Yunnan.

The “Great Game” was heavily influenced by Halford Mackinder’s thought. In 1904 Mackinder argued that the Russian movement eastwards—organizing the Cossacks and policing the steppe—was an event almost as consequential as the rounding of the Cape. A generation before, steam power and the opening of the Suez Canal had seemed to increase the importance of sea overland power, but now transcontinental railways were upsetting the balance, and nowhere could they be seen to work wonders like in the steppe.[18] Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India from 1899 to 1905, was known for his belief that Russian imperialism posed the biggest threat to India.[19] Curzon prepared his influential 1907 Romanes lectures on frontiers with the help of Mackinder’s article, and when he became Foreign Secretary in 1919, Curzon appointed Mackinder as British High Commissioner to South Russia with explicit instructions to gather intelligence on the Bolsheviks and assist the White Russians.[20] The British in India who subscribed to this view of Central Asia, and indeed world geopolitics, as a result, prioritized the defense of India’s north-west frontier over that of India’s north-east frontier with China and Indochina.[21] The government of India, therefore, repeatedly vetoed the various Yunnan railway projects that were presented to it.

The British in Burma, on the other hand, tended to see Yunnan in terms of the competition with France in Southeast Asia. The idea of the possible partition of China urged the British commercial lobby’s promotion of the railway venture. Archibald Little worried that, “while we have been talking the French have been acting”,[22] and in 1897, the Straits Times reported that “France strains every nerve to reach the rich and populous province of Yunnan”.[23] Like the British, the French saw Asia as a source of markets with inexhaustible demand.[24] The French commercial myth of Yunnan was born in the wake of the Garnier and de Lagree expedition to explore the Mekong in 1873. France aimed to pursue a “river policy” in Southeast Asia to rival Britain’s “open door” policy in Canton and along the Yangtze River. The French Yunnan myth would remain powerful for the rest of the century, despite, in 1877 and 1878, the Mekong being shown not to be navigable in the far north.[25] As with the British experience, the French colonial presence in Southeast Asia served as a vehicle for fantasies concerning the fabulous Chinese market, or “a new Louisiana in Tonkin”.[26] However, for most of the century, the government of India remained impervious to the commercial and geopolitical arguments for the expansion of infrastructure from Burma into China, focusing instead on the cost and geographic impracticality.

Shifting alliances

These geopolitical considerations changed in the 1890s, however, as competition with France heated up in Southeast Asia. British policy-makers briefly saw Yunnan and Burma as central to a joint Franco-Russian threat to India’s northeast frontier. For a few years, competition with the French in Indo-China, and fears of the Russians in China, were briefly prioritized over the Great Game in Central Asia. In 1895, therefore, the government of India authorized construction of the railway.

The extent of the concessions to France in south and southwest China after the Sino-Japanese war in 1895 awakened the government of India to the dangers of French encroachment in British Burma. The French “Mission Lyonnaise” then embarked on a commercial expedition to southern China in September 1895. In July 1895, Captain Bowers of the Calcutta Intelligence Branch reported that the French had set their eyes on Yunnan and would cut off communication with the Yangtze valley. He recommended that a private company be approached to build the railway extension from Mandalay to Kunlong Ferry on the Chinese border.

Rosebery, the British Prime Minister, criticized the government of India for focusing too much on the dangers on India’s northwest frontier.[27] Several British Chambers of Commerce petitioned the Foreign Office and the India Office to alert them to the dangers of France securing the only practicable route to south China. Until 1896, Siam had been the main focus of British and French imperial ambitions in the region, but in that year a mutual Anglo-French agreement to maintain Siam’s sovereignty and independence was signed.[28]

All these pressures combined to persuade the government of India to support the building of a railway from Mandalay to Kunlong Ferry on the China border. The India Office enquired in the City of London, and within a week, Rothschilds bank offered to extend a loan.[29]

The Yunnan-Burma railway project seemed to be finally coming to fruition, four decades after it was first proposed. However, another shift in geopolitical priorities quashed the project soon after construction began.

Firstly, Curzon refocused Indian foreign policy by once again prioritizing the north-west frontier. He argued in 1897 that there was “not the vestige of a reason” in favor of building the Mandalay-Kunlong railway, except to quieten the British Chambers of Commerce.[30] In fact, he saw the Franco-Russian rapprochement as a reason not to build a railway to Yunnan. He believed there was a danger of a north-south trunk line through China falling into the hands of the Russians and the French.[31]

Secondly, the mutual fear of Germany and Japan’s growing power drove Britain and France closer together. In 1898, Britain made secret overtures to Germany to form an alliance, but nothing came of them.[32] The efforts to befriend Germany having failed to bear fruit, many ministers viewed an alliance with France as a stepping stone to a proper alliance with Russia.[33] By 1903 a combination of all of these factors drove the erstwhile enemies, Britain and France, together and in 1904, they signed an agreement resolving most of their overseas disputes.[34]

Russia and Britain reacted to Japan’s growing power by reconciling their interests in Central Asia. In 1895 the two countries signed a settlement regarding disputed territory in Eastern Turkestan.[35] In 1899 they exchanged notes, with Britain agreeing not to seek a railway concession north of the Great Wall, and Russia promising likewise in the Yangtze Basin. The two countries thus seemed to have “canceled each other out” in China.[36]

Following Russia’s alliance with France, Yunnan was no longer seen as important either to the competition with France in Southeast Asia or to the defense of India and of Britain’s interests in China. In 1899, therefore, construction on the line was abandoned. Although the French completed their railway from Hai Phong to Yunnan in 1910, the British did not revive the idea for a railway until World War II.

Geopolitical considerations are once more at the heart of talk of a Myanmar-China railway. If this recent plan for a railway goes ahead, the project first promoted by a handful of amateur railway enthusiasts in the 19th century might finally be completed.

Frances O’Morchoe is a lecturer in history at Parami Institute, with a DPhil in Burmese history from the University of Oxford. This article originally appeared in Tea Circle, a forum hosted at Oxford University for emerging research and perspectives on Burma/Myanmar.

NOTES

[1] ‘Mr. Holt Hallett on Burmah and the Shan States’, The Manchester Guardian, 20th January, 1886.

[2] Holt S. Hallett, ‘The Remedy for Lancashire: A Burma-China Railway’, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, September 1892.

[3] James L. Hevia, English Lessons: The Pedagogy of Imperialism in 19th-Century China, Durham: Duke University Press (2003), 12.

[4]Straits Times, 28th March 1898.

[5]The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 19th December 1898.

[6]John Hurd and Ian J. Kerr, India’s Railway History: A Research Handbook, Leiden: Brill (2012), 2.

[7] Ethel Colquhoun, ‘Archibald Colquhoun: A Memoir’, United Empire: The Royal Colonial Institute Journal, 6:2 (1915), 101.

[8]Archibald R. Colquhoun, Across Chryse: Being the Narrative of a Journey of Exploration through the South China Borderlands from Canton to Mandalay, London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington (1883), vii.

[9] ‘Archibald Colquhoun: A Memoir’, United Empire: The Royal Colonial Institute Journal, 6:2 (1915), 102.

[10] Ney Elias, ‘Mission to Western China’, Ney Elias Collection, Number 1: Part I, Archives of the Royal Geographical Society, London.

[11] Elias, ‘Mission to Western China’.

[12]David G. Atwill, The Chinese Sultanate: Islam, Ethnicity and the Panthay Rebellions in Southwest China, 1856-1873, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press (2006), 161.

[13] E.B. Sladen, ‘Burma: Exploration via the Irrawaddy and Bhamo to South-Western China’, Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London, 15:5 (1870-1871), 361.

[14] Elias, ‘Mission to Western China’.

[15] Elias, ‘Mission to Western China’.

[16] Memorandum from Kaye to Argyll, 28th June 1872, Secret Letters to India, IOR L/PS/5/594, British Library.

[17] Proposed draft letter from Argyll to Government of India, India Office, London, 19th July 1872, Secret

Letters to India, (1872) IOR L/PS/5/594, British Library.

[18] H.J. Mackinder, ‘The Geographical Pivot of History (1904)’, The Geographical Journal, 170:4 (2004), 433-434.

[19] C. Edmund Bosworth, ‘The Hon. George Nathaniel Curzon’s Travels in Russian Central Asia and Persia’, Iran 31 (1993), 128.

[20] A.S. Goudie, ‘George Nathaniel Curzon: Superior Geographer’, The Geographical Journal 146:2 (1980), 207; B. W. Blouet, ‘Sir Halford Mackinder As British High Commissioner to South Russia, 1919-1920’, The Geographical Journal, 142:2 (1976), 231.

[21] M.A. Yapp, ‘British Perceptions of the Russian Threat to India’, Modern Asian Studies, 21:4 (1987), 647-665.

[22]Archibald Little, Across Yunnan: A Journey of Surprises, Including an Account of the Remarkable French Railway Line now Completed to Yunnanfu, London: Sampson Low, Marston and Co. Ltd. (1910), 69.

[23]Straits Times, 10th June 1897.

[24]Milton E. Osborne, The French Presence in Cochinchina and Cambodia: Rule and Response (1859-1905), London: Cornell University Press (1969), 13.

[25]Pierre Brocheux and Daniel Hemery, Indochina: An Ambiguous Colonisation, 1858-1954, London: University of California Press (2009), 9.

[26]Osborne, The French Presence in Cochinchina and Cambodia, 33.

[27]Chandran, The Burma-Yunnan Railway, 14.

[28]Chandran, The Burma-Yunnan Railway, 31.

[29]Burma Railways Company loan prospectus (1896), Rothschild archives, London.

[30]Chandran, The Burma-Yunnan Railway, 70.

[31]Curzon to Salisbury, Private, 2nd June 1898, Salisbury Papers, Special Correspondence: Curzon. Quoted from Chandran, The Burma-Yunnan Railway, 67.

[32]Sneh Mahajan, British Foreign Policy, 1874-1914: The Role of India, London: Routledge (2002), 137.

[33]Mahajan, British Foreign Policy, 154.

[34]Nicholas Tarling, ‘The Establishment of the Colonial Regimes’, in Nicholas Tarling (ed), The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, Volume III, From c. 1800 to the 1930s, Cambridge: CUP (1999), 52.

[35]O. Edmund Clubb, China and Russia: The ‘Great Game’, New York: Columbia University Press (1971), 116.

[36]Hevia, English Lessons, 181.