LASHIO, Shan State—Early one morning in late April, U Khu Phan was taken aback when some villagers showed up at his house with puzzled, worried looks on their faces.

The local residents told the village administrator they had found a concrete block embedded in the ground in the middle of their village.

Running to the location, he found the concrete block fixed in the ground nearly 30 feet from his home. It is also just 46 feet from a natural spring on which more than 1,000 residents of three villages rely for their drinking water, agriculture and daily use.

The block turned out to be a marker for the proposed route of a nearly 414-kilometer-long, China-backed railway that will link Kunming, the capital of China’s Yunnan Province, and Mandalay, the second-largest economic hub in Myanmar. The 13-inch-thick object used the Global Positioning System (GPS) system to provide geographical information.

U Khu Phan did not know when the concrete block had been placed there, though he and some village administrators had been summoned to spend several weeks helping Chinese surveyors conduct a ground survey for the Muse-Mandalay railway project.

General Administration Department (GAD) staff and ethnic organizations received an order in early April informing them that they would be required to cooperate with the surveyors and help them measure and observe the railway route from Mandalay to Muse.

“In our estimation, the railway will definitely pass through the middle of our village. So, it will divide the village,” said U Khu Phan, administrator of Nam Hu village in the Nam Tun village tract in Lashio Township.

Situated beside the Muse-Lashio highway, Nam Hu has existed for nearly seven decades, with Shan and Kachin ethnic people living together peacefully. With more than 200 households in the village,

the majority of the people have made a living from subsistence agriculture and animal husbandry for generations.

Some villagers grow seasonal crops and corn to sell to China via Lashio. Lashio is an important gateway for Myanmar-China border trade, serving as an economic and transportation hub as well as an important commodity distribution center in northern Shan State, more than 100 km from the China-Myanmar border.

In short, for Nam Hu villagers, land and water resources are crucial for their survival, providing both their daily meals and incomes. As it mainly relies on agriculture and animal husbandry, they could not imagine giving up their farms and land for the railway project.

Pointing to the mountains around the village, he said, “The railway will also totally destroy the water resources,” adding that villages have been reliant on them for nearly seven decades. The township’s geographical nature doesn’t permit villagers to dig wells for the water supply, as it lies in the highlands.

“We will be dead if they choose this route,” he stressed.

Since discovering the concrete block, and calculating the location of the village and natural spring, the concerns of Nam Hu villagers have gradually reached boiling point.

“We cannot let them use this route,” said U Sai San Tun, a 65-year-old farmer from Nam Hu village.

Railway portion of CMEC

The US$8.9 billion (13.09 trillion kyat) Muse-Mandalay Electric Railway Project is a backbone project of the China Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), which is also an initial part of the strategic China-Myanmar High Speed Railway, which aims to connect Kyaukphyu in Myanmar’s Western Rakhine State with China’s Kunming via Muse.

The CMEC is a part of China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy unveiled in 2013. The MoU for the corridor was signed between Myanmar and China in 2018.

Muse sits on Myanmar’s border with Yunnan province in southwestern China, and is the largest trade portal between the two nations, while Mandalay is central Myanmar’s commercial center, so the railway could become a lifeline for China-Myanmar trade.

Designed to reach speeds of 160 kilometers per hour (99 miles per hour), the electric rail will take only three hours to get from Mandalay to Muse. Currently, Mandalay is connected to Muse via Lashio by a national highway. The drive normally takes more than eight hours.

The transport and communications minister has given full support for the project, saying that the railway is a priority project and a part of Myanmar’s national transport master plan. Myanmar expects it to facilitate exports to China, ease traffic jams on the highway, create jobs and attract technical know-how.

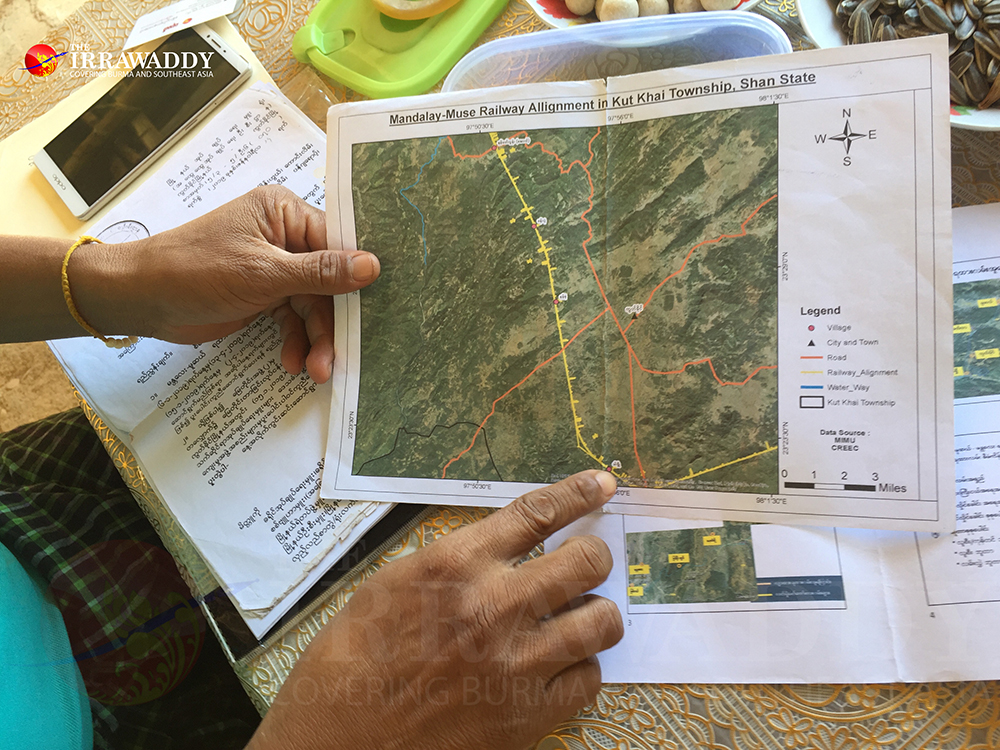

The railway will pass through a total of 11 townships in Mandalay, Pyin Oo Lwin, Naung Cho, Kyaukme, Lashio, Kutkai, Hsipaw, Nam Un, Theinni, Nam Hpak Ka and Muse in northern Shan State near the Chinese border. While the railway route has been finalized, neither side has made it public yet. It’s still unknown how many people and households will be affected by the project.

China Railway Eryuan Engineering covered the cost of the railway’s Feasibility Study (FS), which was submitted to the Myanmar government in April last year during Beijing’s 2nd BRI forum. The FS study included alignment measurements for the route, the number of stations, water samples, and earth, gravel and soil tests.

The Myanmar government was earlier expected to make final decisions on the specific details of the construction by the end of 2019. However, it is still unknown if it has made any decisions.

Local concerns

Villagers in northern Shan State were unaware that the railway is a part of Chinese President’s Xi ambitious plan to build grand infrastructure projects from Asia to Europe.

During The Irrawaddy’s recent weeklong visit to potentially affected areas along the railway line, the majority of local people said they had received no specific information about the project, though they are increasingly fearful of forced displacements, farmland confiscations, losing water resources and the social impacts of the planned project.

“So far, no [government officials] have come to the affected villages to explain about the railway,” said U Win Htein, the administrator of Man Paine Village Tract in Kutkai, another area the railway line would pass through. According to the document obtained by U Win Htein, two villages out of 12 in the village tract will be affected by the projects, and would face possible problems such as land confiscations, farmland loss and harmed livelihoods if villagers have to make way for the project.

“I would like to request the officials show transparency about the project. Now villagers are growing worried about land confiscations and other potential impacts of the project,” U Win Htein said.

In Kutkai, more than 100 households from Kaung Lain village in Mam Lone village tract have been living in IDP (internally displaced persons) camps for several months due to armed conflicts near their village. Adding to their dismay, their one-time homes face destruction to make way for the railway, as it would pass through their village. The Irrawaddy saw a concrete block embedded in the ground at the entrance of the village.

Hkam Nat, who is in charge of the Ta’ang (Palaung) Women Affairs Organization based in Kutkai, told The Irrawaddy that Kaung Lain villagers are worrying that their homes and lands will be grabbed by the local authorities in their absence.

“Those people already suffered ordeals both physically and mentally while they were running from armed conflicts. They should not have to suffer more because of the project,” she said.

Transparency issues

In August, deputy general Manager of Myanma Railways U Ba Myint told the media the route has been finalized. Some township GAD officers have already obtained the details of the proposed railway routes in their townships, including details at the village level.

The Myanmar government has been criticized by think tanks and civil society organizations for lacking transparency when it comes to the BRI projects in the country. Recently, Netherlands-based Translational Institute (TNI) said Myanmar’s government lacks transparency regarding BRI-related documents. The TNI pointed out that other governments like Latvia have publicized BRI-related documents on their official websites, whereas the Myanmar government has not yet made public BRI documents including the CMEC MoU and early harvest project lists agreed between the two countries, including the railway project.

A lawmaker of the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy (SNLD) serving in the Shan State parliament, Nan San San Aye, told The Irrawaddy that despite Chinese projects being geared up for implementation in Shan State, the state government has not yet discussed the project in the state parliament.

“The lawmakers do not have any information about the projects under the CMEC. There is no transparency about it. Actually, they need approval from the state parliament,” Nan San San Aye said.

“We have heard many local concerns about the railway projects. We are planning to ask questions in the parliament,” she added.

Apart from transparency issues, local people feel left out of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process. The EIA for the railway was carried out by the Ever Green Tech Environmental Services and Training Co. Ltd, a Yangon-based local company offering EIA services.

Arranged by local general administration offices, and led by the officials from Myanma Railways, the EIA company and Chinese surveyors, the public consultation meetings were held in major cities in the project areas to explain the benefits and the environmental impacts of the project.

Company adviser Dr. Kyaw Swar Tint told The Irrawaddy that it had held 19 public consultation meetings as of December last year in cities the railway will pass through. He said a scoping report was recently finalized for submission to the Environment Protection Department.

However, local people including village administrators and civil society organizations told The Irrawaddy that the public consultations were done with a group of people who do not widely represent the affected local communities. Only a few elderly people and the local GAD staff from the affected villages were invited.

“Mostly, they talked about the benefits of the project; they rarely mentioned the environmental impacts,” said Mai Myo Aung, a lawyer in charge of a Ta’ang Legal Aid Network based in Lashio. The Legal Aid Network has been giving legal support to local people who have faced legal action for their resistance to other Chinese investment projects like dams and oil-and-gas pipelines.

For the railway project, the lawyer said, the local authorities mostly invited officials from the GAD, rather than people who would be directly affected by the project. He said he saw some people in Ta’ang costumes at the meetings. But they were not the people from the would-be affected villages, despite their appearance.

The costumes “are just for show,” Mai Myo Aung said.

“I am concerned that our people are not well informed about the impacts. As a result, they will suffer,” he said.

The EIA company told The Irrawaddy that the team has discovered that some major environmental and social impacts are likely, including the loss of protected forests and watersheds, waste problems, noise and air pollution, as well as land confiscations, loss of livelihoods and other social problems caused by the massive migration that will likely be prompted by the railway project. According to the feasibility study, 60 tunnels, 124 bridges, 724 road crossings and 36 stations will be constructed along the railway.

Dr. Kyaw Swar Tint said land confiscation will be the biggest problem, as most of the project areas will pass through villages and farmlands. However, he declined to say how many villages or how much farmland would likely be affected.

Even those who did appear at the consultation meetings were curious about the number of people that would be displaced, the amount of farmland that would be seized, and the specific areas that would be used for the project. But neither the authorities from Myanma Railways nor the EIA company answered their questions properly.

The administrator of Naung An Village from Hsipaw Township, U Myint Htay, said, “The meeting was just a waste of our time.”

According to documents from the township administrator’s office, the railway will pass through Naung An Village, which has more than 90 households.

U Myint Htay said that despite people’s concerns over land compensation, the real issue in the long term was the sustainability of their livelihoods.

“We are just farmers. We only know how to cultivate crops. The compensation will run out in a short time. After we run out of money, what will we do for a living? I am concerned that we will lose our livelihood forever,” he stressed.

Making matter worse, the majority of the would-be affected villages along the railway do not have land ownership certificates to prove their rights, despite having lived on and cultivated the land for generations.

In Myanmar, mostly in ethnic areas, people customarily use a shared land ownership system that includes freehold lands, community forest reserves and customary tenure for rotational farming practices.

Under the National League for Democracy government, the newly amended 2018 Vacant, Fallow and Virgin (VFV) Lands Management Law has been criticized by ethnic people for failing to recognize ethnic customary tenure. The ethnic people say the legislation forces existing land users to give up their customary land rights and apply for a 30-year land-use permit, or risk being charged with trespassing.

The NLD set a deadline of March 11 to register vacant, fallow and virgin land for use by agribusiness in accordance with the VFV Law. The law imposes a two-year prison sentence on anyone found living on VFV land without a permit after the deadline. Customary land use refers to either informal or traditional use of upland or lowland areas. However, the law does not provide an official process for recognizing and registering customary land.

According to data released by the Mekong Region Land Governance Project survey in February, 95 percent of people living on VFV land had no knowledge of the law, and a majority of ethnic people missed the deadline.

Mai Myo Aung said, “It is very difficult to negotiate the proper compensation without having ownership documents. The majority of people usually practice customary tenure.”

“According to the newly amended law, all the lands [including homes and farmlands] here could become VFV. I am concerned that they [the railway developer] will have the upper hand when we negotiate the compensation, as the locals do not have official documents,” he said.

At the public consultation meetings, the officials from Myanma Railway said they would set up a team to handle property compensation, but they did not say how they would compensate the majority of people, who do not have official land ownership documents.

“We will carefully watch the project process. If we find out the locals have not received proper compensation, we will offer them legal help,” Mai Myo Aung said.

Further north in Muse Township, the railway line’s final stop on the Myanmar side, another concrete block was placed in the middle of the village of Maw Tawng. If the railway is constructed on that route, the village will face the same fate as other villages on the route. The locals expressed their concerns, including that water resources will be destroyed, as more than 1,200 people rely on them for drinking water, farming and daily use.

Maw Tawng villager Mai Aik Aung, 35, said opinion was divided among locals as to whether to support the project or not. However, the trader said the majority of people don’t accept it.

“Since we don’t have enough information, we will wait and see their next move,” he said.

Even as they fail to keep local people fully informed about the project, officials from Myanma Railways urge local people to accept it, saying it will benefit them economically.

In videos of the public consultation sessions in Pyin Oo Lwin in August obtained by The Irrawaddy, U Htay Hlaing, Myanma Railways assistant general manager said: “It would take only three hours [to get] from Muse to Mandalay. The flow of trade and people will be faster and more convenient. It will be a very beneficial project for the country.”

The Chinese media have also mostly praised the railway, saying it will create jobs and benefit locals economically. Then Chinese Ambassador to Myanmar Hong Liang said in May last year that as most of the Myanmar population lives in rural areas and most of the agriculture products can be exported to China, he was confident that many farmers would benefit from the railway project. Chinese people will also be encouraged to visit Myanmar, he said.

However, such praise does not impress the locals.

“We are not interested in the benefits of the railway. We are worried about our homes and farmlands,” said U San Pia, a farmer from Nam Tun village tract in Lashio.

“It is not possible that the railway carries economic development to our village. I am just a farmer. I sell crops to the traders. The traders export our crops to China. I think the traders and the Chinese will benefit from it,” he added.

In discussions of the possible economic development brought by the railway line, some locals also questioned whether a railway is actually needed for the people in the affected areas.

U Win Htein said, “We have to think about whether it’s worth it. Because we will lose our homes, farmlands, water resources and natural resources.”

“I bet the Chinese will get more benefit than us,” he said.

Besides land grabbing and losing water resources, the local farmers have another serious concern: the expected influx of Chinese migration, and resultant human trafficking, drug abuse and exploitation of natural resources.

The administrator of Nar Kun Long village tract in Lashio, Brang Mai, told The Irrawaddy, “They don’t have moral ethics. They only look out for their own interest. As a normal citizen, I do not want to see a massive influx of Chinese migrants or visitors to our state.”

“The more Chinese, the worse consequences we experience. It is like sacrificing many people for one [group’s] benefit,” he said.

Experts are also concerned that the railway could inflame military tensions as it will pass through ethnic conflicts areas. In August last year, deadly fighting between the Myanmar army and ethnic armed groups broke out in northern Shan State.

“Our state is the most crucial place for all the Chinese projects under the CMEC. The government should suspend all the mega-projects until peace prevails in the region,” Mai Myo Aung said.

“When the projects come while there are conflicts, people will suffer more,” Mai Myo Aung said. The lawyer said that people have suffered enough from the effects of previous Chinese projects including dams and oil-and-gas pipelines.

“They shouldn’t open old wounds by implementing new projects,” he said, referring to the railway project.

In late November, hotels in Lashio were fully booked by Chinese officials and investors attending the 1st Myanmar (Lashio) and China (Lancang) Industrial Zone and Trade Fair. Banners announcing the trade fair were displayed downtown.

With an agenda to promote cooperation in agriculture, tourism, production capacity, infrastructure and industrial parks, the trade fair was attended by U Than Myint, the Union Minister for commerce, and officials from the Chinese Embassy in Myanmar as well as nearly 50 Chinese enterprises.

During the ceremony, Chinese officials pushed the Myanmar government to implement the Muse-Mandalay railway as soon as possible to promote trade cooperation, while the Myanmar government demanded a fair border trading system between the two countries.

In response to the Chinese officials’ push, local environmental organization the Heartland Foundation and nearly 20 civil society organizations recently set up a core team to monitor CMEC activities across Shan State. The team is planning not only to observe transparency issues, and social and environmental impacts, but also to raise awareness about the railway projects among locals.

The project officer of the foundation, U Aung Myo Htun, told The Irrawaddy that it will carefully examine the activities of the projects, especially transparency issues, locals’ concerns, and the environmental and social impacts of the projects and observe whether the projects benefit or harm locals.

Meanwhile, the lives of Nam Hu Village administrator U Khu Phan and his fellow villagers are dominated by worries: they fear the destruction of their village and water resources, and of the farmland they have been tilling for generations.

“As long as they keep the project a secret, the doubt and concerns will keep growing among the people. It is not a good sign for either the Myanmar or the Chinese government,” U Khu Phan said.

What if it proceeds without local consent and in secrecy?

“If they do something on the ground without explaining it, the locals will resist it violently,” he warned.

You may also like these stories:

China Quietly Pushing Myanmar to Back Its Development Plan for Irrawaddy River

Myanmar Watchdog Criticizes ‘So-Called’ Public Consultation Process for China’s BRI Project

Potential Environmental and Social Impacts of Chinese Mega-Projects in Myanmar Raise Concerns