In what can only be described as a waste of time, the new junta, the State Administration Council (SAC), has turned to churning out statements and propaganda pamphlets in an attempt to justify its power grab to the international community. Few, if any, are going to believe its version of events. But in the end, geopolitical realities may prompt even the SAC’s most vocal foreign critics to grudgingly accept the new military government—in particular, the fear of Myanmar once again falling into the clutches of China, and that at a time when the expansion of Chinese influence in the entire Indo-Pacific region is becoming a major issue for security strategists in the West, Japan, India and Australia. Condemnations of human-rights abuses perpetrated by the Myanmar military, the Tatmadaw, will continue, but, behind the scenes, there might be a slow return to the balanced relationship that existed during previous juntas, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (1988-1997) and the State Peace and Development Council (1997-2011).

India’s Chief of Defense Staff, General Bipin Rawat, was the first to publicly express regional security concerns. Speaking at a webinar on “Opportunities and Challenges in North East India” organized by the Indian Military Review on July 24, Rawat stated that India needs to closely monitor the emerging situation in Myanmar where China, he said, is making further inroads after international sanctions were imposed on the country after the Feb. 1 coup: “The BRI [Belt and Road Initiative] of China is bound to get further impetus with the sanctions on Myanmar.”

India has reasons to be worried about developments in its northeastern states, northern Myanmar and China. From the 1960s to the mid-1970s, China trained and actively supported rebels from Nagaland, Mizoram and Manipur. Even after the end of direct Chinese support, Naga, Manipuri and later also Assamese insurgents have been based in the remote mountains of northwestern Sagaing Region, from where they have launched raids into India and then retreated back across the border beyond the reach of India’s security forces. Those cross-border raids were supposed to have ended when the Myanmar army, after decades of neglect and denial, finally yielded to Indian pressure in February 2019 and attacked and captured Taga, a sprawling camp in northern Sagaing where Nagas, Manipuris and Assamese rebels had long been based. But the rebels simply regrouped and launched more cross-border raids into northeastern India. The rebels are equipped mostly with arms obtained by intermediaries from Chinese sources or the illicit arms market in Southeast Asia. Unofficial representatives of insurgent groups from Manipur and Assam are based in Ruili and other towns near Yunnan’s border with Myanmar, where they maintain low-level contacts with Chinese security services.

China has never publicly admitted that they are there, but in October last year, when India entered into an official trade pact with Taiwan, the authorities in Beijing hit back via its mouthpiece, Global Times. Long Xingchun, president of the Chengdu Institute of World Affairs, a think-tank administered by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, wrote in an op-ed piece on Oct. 22 that “once a country wants to develop official trade ties [with Taiwan], it is by no means purely a trade issue…if India supports Taiwan secessionist forces, China and India will come to hostility, especially if the India’s moves [sic] force China to support secessionist forces in India as a countermeasure. Each would attack the weakness of the other.”

The “secessionist forces” that China threatened to support would without doubt be the rebels from India’s northeast. Guns and other equipment could be smuggled through northern Myanmar, and instability there is, from an Indian point of view, a security nightmare. The aftermath of the coup has created such conditions and with a Myanmar firmly entrenched in the Chinese sphere of influence, the Tatmadaw would have no incentive to intercept arms transfers to India’s rebels.

India may be a democracy, but as Kanwal Sibal, a former Indian foreign secretary, wrote in an op-ed in the Times of India on April 13: “We’re not in the business of democracy promotion. Our interests come first.” Without cooperation with the Myanmar military, Sibal wrote, “our security issues in the Northeast will become grave affecting not only peace but also the larger geo-political eastward ambitions of India.” Therefore, Sibal argued, India would have to handle the post-coup influx of refugees from Myanmar “with sensitivity and preserve our capacity to engage the Myanmar military to cooperatively deal with developments on the ground.

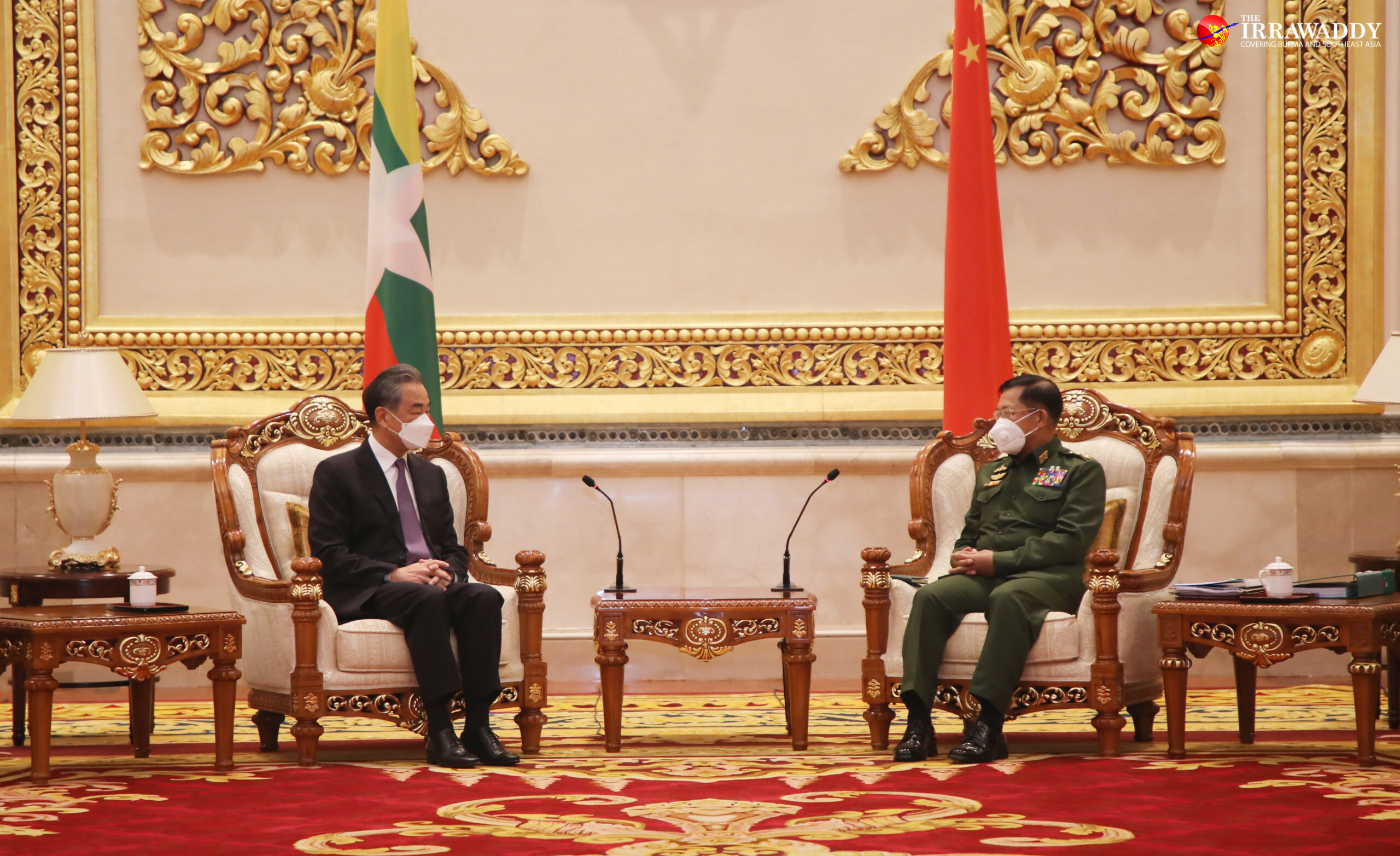

That would include cross-border trade as well as keeping Chinese influence at bay — and China has made some important gains since the coup. On June 5, the Chinese ambassador to Myanmar, Chen Hai, met SAC chairman Senior General Min Aung Hlaing in Naypyitaw, becoming the first leading diplomat to do so. The meeting amounted to a de facto recognition of SAC rule and the government it has appointed.

Three days later, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi held talks with his junta-appointed Myanmar counterpart Wunna Maung Lwin, who was paying what a Chinese Embassy statement called “a working visit” to Chongqing in China. “China’s friendly policy towards Myanmar is not affected by changes to Myanmar’s domestic and external situation,” the statement said, and Wang pledged to “continue to support Myanmar in fighting the [COVID-19] pandemic, provide vaccines and medical supplies, help the country in public health and enhance cooperation on joint pandemic prevention and control with Myanmar in border areas.” Wang failed, however, to mention that all such aid would have to go through the military and its agencies and that, so far, it’s the military rather than the civilian population that’s benefited from Chinese assistance. Then, on Aug. 11, China announced that it will transfer over US$6 million to Myanmar’s military government to fund 21 development projects within the framework of the Mekong-Lancang Cooperation initiative that China has undertaken to extend its influence over Mekong River nations. The grant is said to include animal vaccines, culture, agriculture, science, disaster prevention and, curiously, tourism.

India is not the only country watching these developments with anxiety. Japan has not joined the West and introduced sanctions, or even come out to strongly condemn the killings, arrests and torture of opponents to Min Aung Hlaing and his SAC. The China factor haunts again. Yusuke Watanabe, secretary general of the Japan-Myanmar Association, wrote in The Diplomat of May 26 that shortly after the coup he found himself “to be one of few foreigners in constant contact with Myanmar’s current de facto leader, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing” and that “my enduring engagement with him underscores Japan’s near century-long special relationship with Myanmar, an oft-forgotten geopolitical factor crucial to resolving the present crisis as China’s clout overshadows the future of a free and open Indo-Pacific.”

Seen in a broader perspective, India and Japan share the same fundamental security concerns with the United States and Australia. Those four countries are part of what’s called the Quad, or the Quadrilateral Security Dialog, and have held joint naval exercises in what is seen as a response to increased Chinese economic and military power in the Indo-Pacific region. On Aug. 2, Indian authorities announced that yet another such Malabar Exercise, as they are called, will be held in the western Pacific later this year. Last year’s Malabar Exercise by Quad members was held in the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea.

Support for Myanmar democracy may well become a victim of those geostrategic concerns. Myanmar is China’s corridor to the Indian Ocean and if Min Aung Hlaing’s junta can’t be dislodged from power, countries that are engaged in containing Chinese expansion may have no other choice than to find some way of cooperating with it. India can do and say so openly, Japan and Australia more quietly—and the United States would turn a blind eye when talks and other exchanges are taking place with Myanmar’s military.

In the old junta days, analysts such as Marvin Ott, then a professor of National Security Policy at the National War College, weighed the merits of a pragmatic approach. Ott wrote an article for the Los Angeles Times on June 9, 1997 arguing that while US Myanmar policies “reflected moral outrage”, condemnations and sanctions had only pushed “Myanmar into China’s orbit.” Ott wrote that one side of US foreign policy could be described in terms of an “idealist” impulse to use policy to further “American political values, notably democracy and human rights.” But the other, he argued, is a geopolitical “realist” approach that stresses the pursuit of national interests. No one in the US has dared to voice a similar opinion today, but the longer the SAC remains in power, the more likely it will become that such views will be heard once again.

But such an approach could also be deemed to be a simplistic way of looking at a huge and complex problem. The future of the SAC is far from certain, and what would happen in the unlikely but not impossible scenario that it falls? Or if relations between the SAC and China turned sour? It is hardly a secret in military circles that Min Aung Hlaing has long been wary of the designs that Myanmar’s aggressive northern neighbor has on the country and feels more comfortable dealing with distant Russia. In a surprisingly candid interview with the Russian state-run TV channel Zvezda on July 2, 2020, Min Aung Hlaing said that “terrorist groups” active in Myanmar were backed by “strong forces”, which could only be China, as the Tatmadaw had in November 2019 recovered a huge cache of Chinese-made weapons from the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, a Palaung rebel group. Russia, on the other hand, has been praised by the senior general himself as a “true friend”. Tacitly allowing arms to flood across the border is part of China’s double-faced Myanmar policy: support for whatever government is in power in Naypyitaw, while maintaining close contacts with ethnic insurgent groups in northern Myanmar.

Newly imposed pandemic-motivated restrictions on cross-border activities have also angered Min Aung Hlaing’s government, which is eager to get the crumbling economy back on its feet. In what is said to be an effort to crack down on online fraud, China has also ordered all its citizens to leave areas in northeastern Myanmar controlled by the United Wa State Army (UWSA) and other ethnic armed groups that have de facto ceasefire agreements with the Tatmadaw. The pullout has caused serious problems in those territories, which depend on trade and other economic exchanges with China. The UWSA, by far the strongest and best-equipped ethnic armed organization in Myanmar, could therefore be a new player in the turmoil that Myanmar is going through.

For the time being, Western policy makers appear to be biding their time and playing it safe by outsourcing all the dilemmas surrounding the Myanmar issue to ASEAN—which they must know full well is a nonstarter because of the political and diplomatic impotence of the bloc. But sooner or later, the West will have to do something in order to defend its geopolitical interests in the region. And that “something” will depend on what happens next in China-Myanmar relations. Policies could also be determined by the outcome of ongoing internal upheavals in Myanmar. If worst comes to worst, the region could even end up having a failed state in its midst. The only thing that could be said with certainty right now is that the situation in Myanmar has not been this volatile—and therefore unpredictable—at any time since independence in 1948.

You may also like these stories:

2,000 Myanmar Junta Soldiers and Police Join Civil Disobedience Movement

US Vice President’s Visit to SE Asia Sends Signals to ASEAN

Myanmar Junta Tells Troops to Be Combat Ready at All Times