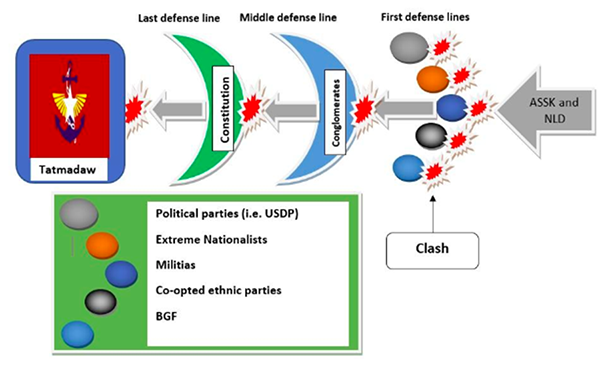

Political analyst Igor Blazevic, a keen Myanmar observer, once outlined the three major defense lines of the Tatmadaw, or Myanmar military, for maintaining its power.

The Tatmadaw’s first, or front, defense line consists of political parties, nationalists, militias and border guard forces (BGFs). The second, or middle, defense line comprises the military’s business conglomerates and cronies. The last defense line is the Constitution, which the military drafted itself.

State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her ruling party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), swept to power in the 2015 general election. Amending the Constitution was one of her campaign promises and remains a party priority. At a forum in Singapore in August, the state counselor said “amendment of the Constitution was one of the goals of our government,” reaffirming her commitment to the cause.

At the NLD’s initiative, the Union Parliament in February formed the Constitution Amendment Committee to draft changes to the charter. Thousands of people, including the chief minister of Irrawaddy Region, have rallied around the country in support of the effort

But there is a critical question – possibly even a life-or-death question — facing Daw Aung San Suu Ky, the NLD and their allies: To what extent do they want to shake the Tatmadaw’s defense lines? The fact is that the Tatmadaw designed the Constitution to be the last one.

The front defense line

The front defense line comprises political parties, nationalists, militias and BGFs. There might be many political parties in the front line, but the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) is the most visible. A group of ex-military generals led by Maj. Gen. Soe Maung recently formed the National Politics Democratic Party. There may be some other proxy and co-opted ethnic parties affiliated with the USDP as well.

The extreme nationalists comprise ex-military service personnel, some Buddhist monks, military families and some ethnic Bamar. They normally organize demonstrations in support of the Tatmadaw to condemn the United Nations for accusing the military of human rights violations and to support the Tatmadaw’s offensives against ethnic armed groups. The prominent Buddhist monk U Wirathu led thousands of nationalists in a demonstration against amending the Constitution in February.

The militias and BGFs are a regular tool of the Tatmadaw. For example, the Tatmadaw and the Karen BGF cleared the New Mon State Party’s outpost near Ka Na Lo Village in Mon State’s Kyaikmaraw Township in June 2018. The militias and BGFs will stand with the Tatmadaw so long as they have the Tatmadaw’s protection. All these groups, from the USDP to the militias, play a big role in Myanmar’s transition to democracy, meaning they can block reforms if those reforms hinder their interests. The USDP, for example called for dissolving the Constitution Amendment Committee on Wednesday.

The middle defense line

The middle defense line comprises the business conglomerates owned by the Tatmadaw or by its officers and cronies. The Tatmadaw launched Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited (UMEHL) — now the Myanma Economic Holdings Public Company Limited (MEHPCL) — and the Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC) to serve its interests.

Since the MEHPCL went public in 2016, it appears that “Type A” shares are still owned by the Ministry of Defense and the Directorate of Defense Procurement. The “Type B” shareholders might include some civilian businessmen along with military personnel, former servicemen, regiments and units.

The MEC is owned by the Defense Ministry and operates in strategic sectors ranging from ports to telecommunications. It has dominated several private domestic firms and signed joint venture agreements with foreign companies.

Business cronies are also part of the Tatmadaw’s defense line. They have close personal and business connections with military officers and political elites. Some have forged close connections with top generals by arranging marriages between their sons and daughters.

The last defense line

The Tatmadaw’s last defense line is its Constitution. It was well designed by the military to prolong its power.

The Constitution gives the military political influence and veto power via a number of legal safeguards. It also grants the military a role in “the national leadership of the state” and makes it the principal defender of the Constitution.

The Constitution also grants the military up to 25 percent of the seats in the national and regional legislatures.

The National Defense and Security Council (NDSC), meanwhile, is the most powerful body and has the final say on any major issue. It is comprised of 11 people from the military (the commander-in-chief, deputy commander-in-chief, first vice president, defense minister, home affairs minister and border affairs minister) and the civilian government (the president, second vice president, the speakers of both houses and foreign minister). The military holds the majority of votes with six to five.

What’s more, three powerful ministries — namely Defense, Home Affairs and Border Affairs — are all controlled by the military. The ministers are directly appointed by the commander-in-chief of the military. The Defense Ministry controls the armed forces and the Border Affairs Ministry oversees the borders, including border trade. The Home Affairs Ministry controls the police force.

Touching a taboo

Amending the Constitution touches a Tatmadaw taboo. The NLD is believed to want to amend more than 160 articles of the Constitution, but the Tatmadaw has already warned that it will not tolerate any amendments that harm the charter’s essence.

Article 20 (f) assigns the Tatmadaw primary responsibility “for safeguarding the Constitution.” As the principal protector of the Constitution, the Tatmadaw presumably has the final say on what that means. Thus, the Tatmadaw appears to have designed the Constitution as a defense line to maintain its power.

The Tatmadaw’s first and second defense lines may be touchable, but only time will tell if Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD can shake the last one.

Joe Kumbun is the pseudonym of an analyst based in Kachin State.