PANGHSANG, Wa Self-Administered Zone—U Than Soe Naing, a former Communist Party of Burma member, was impressed to see how much Panghsang had changed since he and his comrades stayed there in the 1980s when they fought against the socialist regime led by General Ne Win.

“It’s impressive,” said the 73-year-old, who now lives in Yangon, upon his return to the town after three decades of absence. Many ex-CPB members who returned to attend the United Wa State Army (UWSA)’s 30th anniversary celebration felt the same.

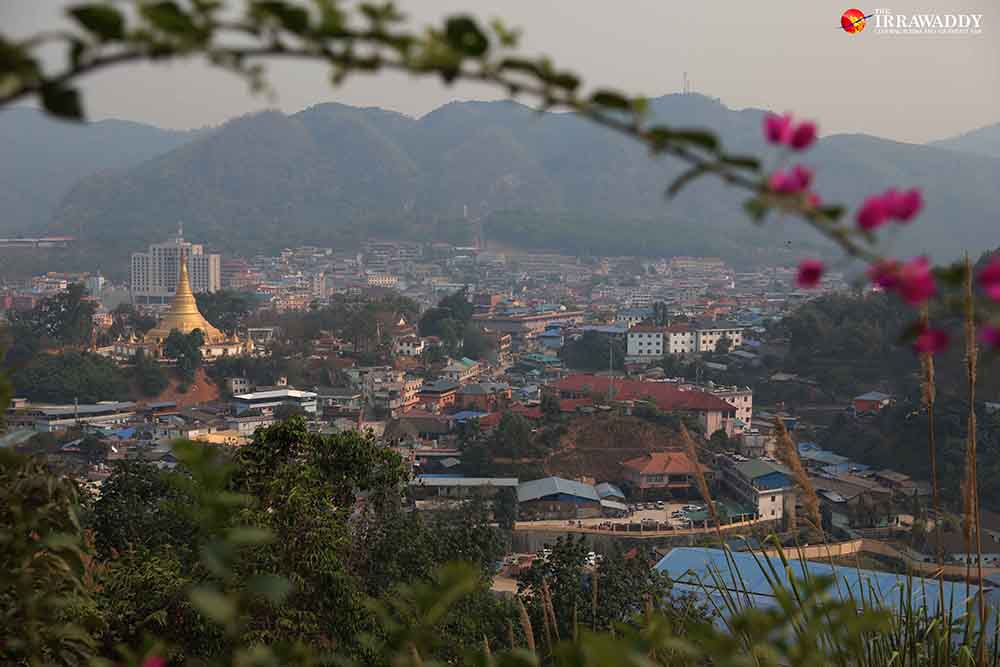

Thirty years ago this town on the Chinese border, now the site of the UWSA’s headquarters, was a small village of clay houses and dirt roads with no electricity and very few vehicles. Soldiers, CPB politburo members and Wa and Shan villagers strolled around its streets.

Since then, Panghsang’s residents have seen dramatic changes after Wa leaders reached their first ceasefire agreement with Myanmar’s ruling regime, then known as the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC). There have been no serious clashes between Myanmar and Wa forces since then.

In contrast to the Shan village it was in the 1980s, Wa police now direct traffic and visitors can see Chinese-style shop houses, hotels, casinos and small and medium-sized shopping malls. Underground cables are in place, and luxury four-wheel drive cars ply the roads. There is a taxi service, well-constructed paved roads, nightlife entertainment and Chinese restaurants.

Located in northeastern Shan State, Panghsang remains isolated, however. Aside from the many Chinese visitors from across the border, there are no tourists on the streets and very few Westerners have been there. Despite the beauty and landscape of the region, Wa leaders are reluctant to allow tourists to come and see it and anyone who does visit must be cleared by both the Myanmar and Wa authorities. According to the Myanmar government, the Wa region is still a restricted area, so foreigners need permission to visit.

Panghsang itself is now indistinguishable from any Chinese city; even the shops signs are all in Chinese. But this area is part of Myanmar, known officially as the Wa Self-Administered Zone. The population of Panghsang includes several of Myanmar’s ethnic groups including Wa, Shan, Lahu, Akha and Palaung. There are also sizable Bamar and Panthay Muslim communities living in some quarters. With a population of around 500,000, Wa region may be off limits to tourism but it is expected that in the near future many more Chinese investors and migrants will flock in.

Wa leaders have transformed this little village into a bustling city. There are many ongoing construction projects and in the next 10 years the city will no doubt undergo many more changes, with new infrastructure projects connecting northern ethnic cities along the border with China and Thailand.

The promise of economic prosperity has seen a steady stream of economic migrants from Shan State and central Myanmar arriving in Panghsang, where they can earn more money and save more. As soon as we entered the Wa region, the roads improved compared to those on the Myanmar-controlled side. The ride from Mong Mao Township to Panghsang on the highland road constructed by a Chinese company is surprisingly smooth.

Chinese is an official language in the Wa region, and residents use Chinese currency, the WeChat Chinese social media application, and Chinese mobile networks. However, the Wa are not Chinese—they are a Mon-Khmer-speaking group whose closest ethnic relatives in Myanmar would be the Palaung or the Mon. But they have definitely compromised and are paying a heavy price for being too close to China.

Once you arrive in town, you feel you are visiting China, not Myanmar; Chinese and Wa are the most commonly used languages, though you can hear Burmese in some quarters. Recently, however, Wa authorities ordered that shop signs must be displayed in three languages: Chinese, Wa and Burmese. This was interpreted by many in Panghsang as a signal that the Wa region is still under Myanmar sovereignty.

The Mutiny of 1989

In February 1989, CPB leaders faced a mutiny as Wa leaders seized its headquarters. The CPB leaders, who were mostly Burman, fled to China unharmed. CPB leaders captured the Wa hills as early as the 1970s but after the mutiny they took sanctuary in China.

Since then the former CPB has split along ethnic lines into four different forces. The Wa region was designated as a special region along with those of the Kokang and some other ethnic groups.

Subsequently, the ethnic Wa minority was among the groups who reached a ceasefire with the SLORC military regime. General Khin Nyunt, the highly feared intelligence chief and Secretary 1 of the SLORC, led the negotiations and reached a ceasefire deal with several ethnic groups in the north including the Wa.

Gen. Khin Nyunt’s faction assisted the Wa region with development aid, building schools and hospitals and sending supplies there. The Wa enjoyed a special relationship with the Gen. Khin Nyunt-led faction and still see him as the godfather of peace in the region. Even today, Wa leaders speak fondly about Gen. Khin Nyunt, who has been accused of turning a blind eye to illicit trade in the region.

Since the collapse of the CPB and the ceasefire deal with the regime, Chinese investment has surged and cross-border trade has skyrocketed. Prosperous China stands behind the Wa region and there is no doubt that the Wa have benefited from China’s economic growth since the time that Beijing, under paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, launched many changes including its open market economic policy.

Chinese companies from Yunnan in particular have developed strong business ties with the Wa and other ethnic groups and have been involved in mining, logging, crop substitution and many construction businesses; to engage in these businesses one doesn’t need approval from the central government of Myanmar.

Since the ceasefire the Wa have had no serious clashes with the Myanmar Army. In fact, they fought alongside Myanmar troops against drug lord Khun Sa’s Mong Tai Army.

Khun Sa surrendered to Myanmar authorities in 1996. In 1999, Gen. Khin Nyunt allowed the United Wa State Party/United Wa State Army to relocate over 80,000 Wa villagers to southern Shan State along the border with Thailand across from Chiang Rai province. This area became the “southern Wa region” known as Mong Yawn.

The area is controlled by warlord and senior UWSA commander Wei Hsueh-kang, who is still wanted by the U.S. on drug-trafficking charges.

Today, Wei is still at large. But he is extremely wealthy (some in Wa circles claim that he is a billionaire businessman and he is believed to have investments in China). The shadowy figure asked Wa leaders not to publish any of his photos in official versions of a book published to mark the UWSA’s 30th anniversary. He remains a mysterious figure and the subject of much speculation. He lives in Panghsang and frequently travels to the southern Wa region and China. Researchers’ repeated requests to visit the southern Wa region are routinely denied. The area is also believed to be a main center of yaba and crystal meth production.

Wa leaders now say they want to improve their image. They claim to have banned the drug trade and insist they now invest in rubber and tea plantations, tin mining and cross-border trade. Cross-border trade between Wa and China in Panghsang is worth more than US$1 billion. In recent interviews, Wa leaders have tried to show that the wealth they are building is not based on drugs. But this hasn’t convinced skeptics and some other observers; in Myanmar, many militias and ethnic armed groups are implicated in the drug trade—this is a simple fact.

Many ethnic armed groups in the north, including the Wa, are heavily involved in illicit trades including drugs; not surprisingly, improvements in infrastructure in recent decades have also facilitated this lucrative business, which is worth billions of dollars.

According to a recent report from the Brussels-based International Crisis Group (ICG) titled “Fire and Ice: Conflict and drugs in Myanmar’s Shan State”, “Good infrastructure, proximity to precursor supplies from China and safe havens provided by pro-government militias and in rebel-held enclaves have also made it a major global source of high purity crystal meth.”

The report goes on to say, “There is comparatively little direct violence between drugs trade actors, who prefer stability. But lucrative revenues earned by various armed actors are helping to fund and sustain Myanmar’s 70-year-old civil conflicts,” the ICG report said.

The drug trade is no doubt a main source of revenue for armed groups and militias. The ICG cites “huge profits fueling greater militarization in Shan State”, thereby undermining the peace process.

Indeed, militias allied with the Myanmar Army and ethnic armed groups in the north are involved in producing crystal meth and yaba, and the profits are likely to be several billion dollars per year. According to the ICG report, “a significant proportion of these profits may remain outside Myanmar, laundered through casinos in border zones and kept in bank accounts in regional financial centers.”

One can see ongoing construction projects in Panghsang and in surrounding areas. They are civilian and military facilities; more and more upscale villas have been built in recent years, visitors have noted. Military vehicles are busy and soldiers are always moving to unknown destinations and undergoing training. In restricted military areas one gets the impression that the Wa are definitely digging in.

Ups and Downs with Central Gov’t

Relations between Myanmar authorities and Wa leaders deteriorated in late 2000. Gen. Khin Nyunt was purged in 2004 and the entire intelligence apparatus was terminated. In April 2009, the regime’s leaders announced a plan to transform ethnic armed groups into the Border Guard Force, or BGF. Some ethnic groups agreed to the proposal but the Wa and other ethnic groups such as the Kokang (known as the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army or MNDAA), and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) refused. The Kokang are the Wa’s closest allies. The Kachin and Wa are still competitors, but both belong to the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC), the alliance of groups based in the north established by the Wa in April 2017.

In the past, the Wa’s sweet deal with Gen. Khin Nyunt saw the region receive aid and development assistance from Myanmar, including the stationing of teachers and nurses there.

But there have been restrictions on the Wa region since the outbreak of its conflict with the MNDAA in 2015. The conflict erupted in February 2015 when MNDAA troops tried and failed to retake the Kokang Self-Administered Zone.

The Myanmar Army suspected the Wa of helping the MNDAA fight against Myanmar troops. Since then, rice, cooking oil and other goods have not been allowed to enter the Wa region. Wa leaders bitterly complain that the central government and military have imposed sanctions on the region. “This is part of the ‘four cuts’ campaign,” a senior Wa leader told The Irrawaddy, referring to the military’s infamous four cuts counterinsurgency strategy.

Nonetheless, social and cultural connections with central Myanmar remain. Wa leaders send their children to study in Yangon and Mandalay. Currently, over 300 Wa students are studying in Yangon. Wa leaders also feel that in negotiations with Myanmar they need to speak Burmese, some ex-CPB observers noted. Perhaps the new generation of Wa is trying to catch up by learning Burmese and integrating.

The establishment of the FPNCC by the Wa was a bold political move. The bloc comprises seven ethnic armed groups: the UWSA, KIA, MNDAA, Ta’ang National Liberation Army, Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army, National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA) and Arakan Army. The UWSA serves as the chair of the FPNCC and has built liaison offices for all member groups at a base in Panghsang.

Since the formation of a new group known as the “Northern Alliance” they have entered several rounds of talks with the government and military leaders, but so far there has been no breakthrough. But Wa leaders quietly say they don’t have to sign the NCA, as they reached a ceasefire agreement 30 years ago, and just want to be involved in the decision-making process in political dialogues and peace conferences, as other NCA signatories are. As a rule, non-NCA signatories are merely observers and not allowed to make decisions in dialogues.

The government and military refuse to allow the MNDAA, AA and TNLA, which are relatively new groups, to participate in the peace talks. The Myanmar Army refuses to recognize new armed groups set up during the government led by former President U Thein Sein. In any case, these three groups have received strong backing from the Wa.

Among the FPNCC members the Wa are the heavyweights; it is hardly surprising that many in the alliance secretly admire the Wa’s rising power and its self-administrative political system.

For instance, the Arakan Army leaders have said openly they want to obtain for Rakhine State a confederate status similar to the one the Wa region has. But Kachin leaders prefer equality and federalism, and it is not certain that the Wa have complete trust in the Kachin. Among the Northern Alliance groups, the Kachin have strong connections with the West.

Military Strength

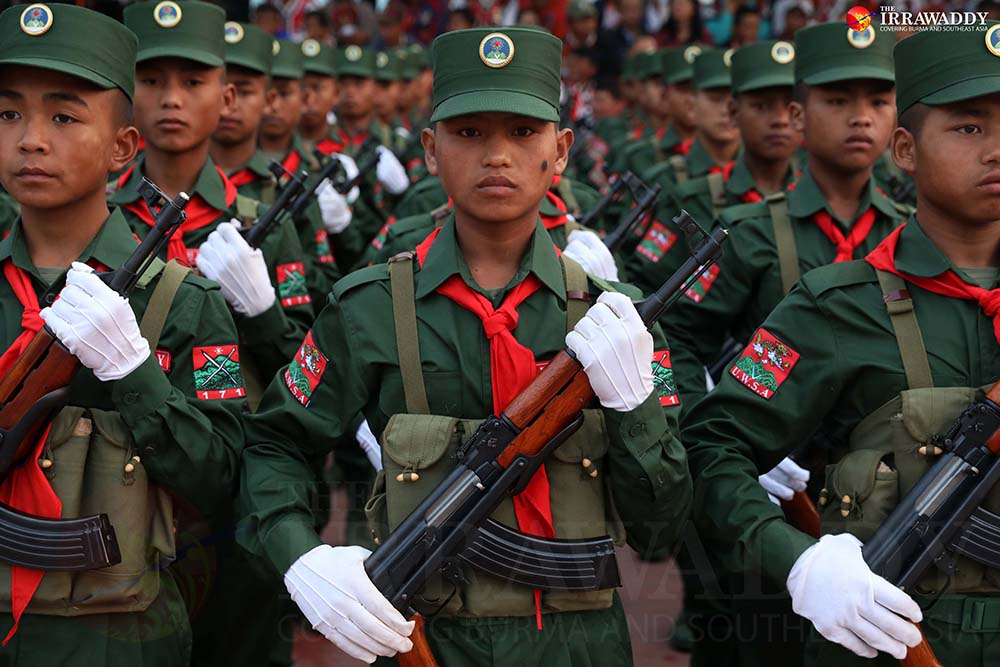

The UWSA has 30,000 soldiers and 20,000 auxiliary troops, making it one of the strongest ethnic armies in Myanmar. Wa leaders now want to equip their forces with even more sophisticated weapons.

Journalists and visitors are not allowed to visit military camps and bases in the Wa region. This is understandable, but we managed to observe during our visit that the Wa have been purchasing more weapons from China and are also producing heavy weapons in their own factories.

Chinese technicians are invited to provide advanced training in the production of artillery and other weapons. Informed sources said the Wa produce 122-mm howitzers in their own factories.

They have also hired Chinese military drone specialists. Panghsang reportedly has three helipads where Myanmar government and military officials’ helicopters land when they visit.

In the past, U.K.-based Jane’s Defense Weekly reported that China delivered several Mil Mi-17 “Hip” helicopters (some reports said five helicopters) to the UWSA in late February and early March 2013, citing sources from the Myanmar government and the military wing of an ethnic rebel group.

Mid-ranking Wa officials we spoke to would neither confirm nor deny the report, but informed sources close to the Wa said it is highly unlikely, as the Myanmar armed forces would never allow ethnic insurgents to operate helicopters or jet fighters in its air space.

Myanmar bought 16 Joint Fighter-17 (JF-17) aircraft from Pakistan to protect its air space to deter foreign threats. The JF-17 Thunder (also named the FC-1 Xiaolong) multi-role fighter was developed by Chengdu Aircraft Corporation (CAC) of China and is jointly manufactured by Pakistan and China. Myanmar Army leaders are also buying more advanced jet fighters from Russia. According to news reports, Russia has begun assembling six Su-30SM fighters for the Myanmar Air Force.

But Wa leaders are flexing their muscles. As the region’s prosperity grows, some Wa leaders have begun thinking about acquiring sophisticated military drones and helicopters. But the Wa will no doubt ask for training and support from Chinese technicians. Some observers also believe the Wa will keep some of its heavy weapons in neighboring countries such as Laos.

Intelligence reports suggest the Wa are building a small airfield between Mongmao and Panghsang. In the past, any suspicions that the Wa might be building an airfield in their region would prompt the Myanmar Army and officials involved in peace talks to immediately ask the Wa to stop the construction project.

The UWSA was expected to flex its military muscles during the parade on April 17 by showing off its arsenal.

According to Asia Times, the UWSA’s arsenal includes new batches of basic infantry systems fielded in the CPB era: light and heavy machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades and mortars, and recoilless rifles. But there are other entirely new systems and these include more modern Chinese infantry weapons such as the QBZ-95 assault rifle only adopted in bulk by the People’s Liberation Army in the early 2000s. The new QBZ-95 has been acquired to supplement locally produced Wa copies of the Chinese T-81 assault rifle. Modern Chinese CS/LS06 9mm sub-machine guns and M-99 12.7mm anti-materiel rifles also mark new additions to the Wa arsenal, Asia Times reported.

The UWSA has also installed an air defense system, which incorporates radar stations and MANPADS (man-portable air-defense systems) and bought anti-tank missiles. According to an Asia Times article published a few weeks ago, “The acquisition of new tactical trucks and, more strikingly, China’s Xinxing (New Star) wheeled armored personnel carriers (APCs) have given a new boost to infantry mobility.”

However, in spite of the high expectations that the Wa would show off its latest purchases of arms and weapons at the 30th anniversary, it was a surprisingly modest show of force.

A senior Wa officer told The Irrawaddy, “We are not so imprudent as to show our weapons at the anniversary,” then smiled and walked away. The UWSA definitely doesn’t want to make it easy for the Myanmar generals to estimate its strength. This is seen as a wily decision by the Wa, who are eager to shed their image as “wild tribesmen and headhunters” and demonstrate that they are no longer prone to acting in an ill-advised manner. Indeed, the UWSA now routinely hires Chinese military advisers, many of them retired defense industry employees.

So what do they want? Separation or autonomy?

Even if the Wa declared itself separate from Myanmar, China would not accept it, so this move is unlikely. China can’t afford to antagonize the government and military in Naypyitaw, which would be at odds with its interest in building stronger economic and geopolitical strategic ties with Myanmar. The Chinese, who are now playing the role of “peace broker” between the Myanmar government and ethnic armed groups, will be happy to keep the Wa—whom they view as indispensable and a “little brother”—as a buffer on the border.

Wa leaders know they can’t entirely trust China. Each time Myanmar generals pay a visit to Beijing, they are anxious and agitated. Before the Wa anniversary, Myanmar military chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing visited Beijing, where he held talks with Chinese President Xi Jinping. He also met with Central Military Commission member and Joint Staff chief Genera Li Zuocheng, held talks with leaders of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army and toured training schools, factories and other significant places. This move no doubt agitated Wa leaders.

Even at the 30th anniversary, Wa leaders were anxiously awaiting final confirmation that Sun Guoxiang, special envoy for Asian affairs of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, would show up. But the Chinese did show up at the last minute, so the Wa and other ethnic alliance members were happy.

During the celebration, Wa leader and commander-in-chief Bao Youxiang demanded autonomy for his region.

“What we need is ethnic equality, ethnic dignity, ethnic autonomy, and we ask the government to give the Wa an autonomous ethnic state; then we will fight for our lives.”

He added: “Until our political demands are realized, we will hold high the banner of peace and democracy on one hand, and armed self-defense on the other, and maintain the status quo.”

The Wa no longer feel like outcasts, but declare their presence with full pride. This is going to be a serious challenge to Naypyitaw. They will keep building their forces as leverage in negotiations with the Myanmar government and military, neither of whom are trusted by the Wa.

The message is clear: There will be no surrender. The Wa want to improve upon the status quo. In order to negotiate from a position of strength—and not necessarily to fight—they feel they must build up the strongest army they can.

Aung Zaw is the founder and editor-in-chief of The Irrawaddy.