It is no secret that a majority of Myanmar people want Ambassador U Kyaw Moe Tun to remain at the UN. They want him to represent their country, but not the junta that staged a coup in February. The message from the people is clear: Deny legitimacy to the junta, known as the State Administration Council (SAC).

Last week, news of an informal gentlemen’s agreement between the US and China to keep the UN ambassador in his post until November was met with a mixture of excitement and interest in Myanmar and beyond. But why China? Beijing had until then been a reliable ally of the regime at the United Nations Security Council (UNSC).

Former members of the ousted government led by the National League for Democracy (NLD) also want U Kyaw Moe Tun to remain in the post. State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who is now under house arrest, will be delighted to hear the news that U Kyaw Moe Tun will stay on at least until November.

The UN Credentials Committee agreed to defer the discussion on the fate of Myanmar’s diplomatic representation until then; the regime has proposed a new ambassador to represent Myanmar at the world body.

Many analysts would love to know whether State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her ministers—including U Kyaw Tint Swe, the Union Minister for the Office of the State Counselor, who is now also under detention—had any inkling of the tragedy about to befall the country in the days leading up to the coup, and if so, what plans they made. These would surely have included a strategy to seek to deny the junta legitimacy at the world body if a coup took place.

Most importantly, what message and instructions Daw Aung San Suu Kyi had for U Kyaw Moe Tun is anyone’s guess. One assumes, however, that the NLD leaders would have wanted him to continue to represent the NLD government.

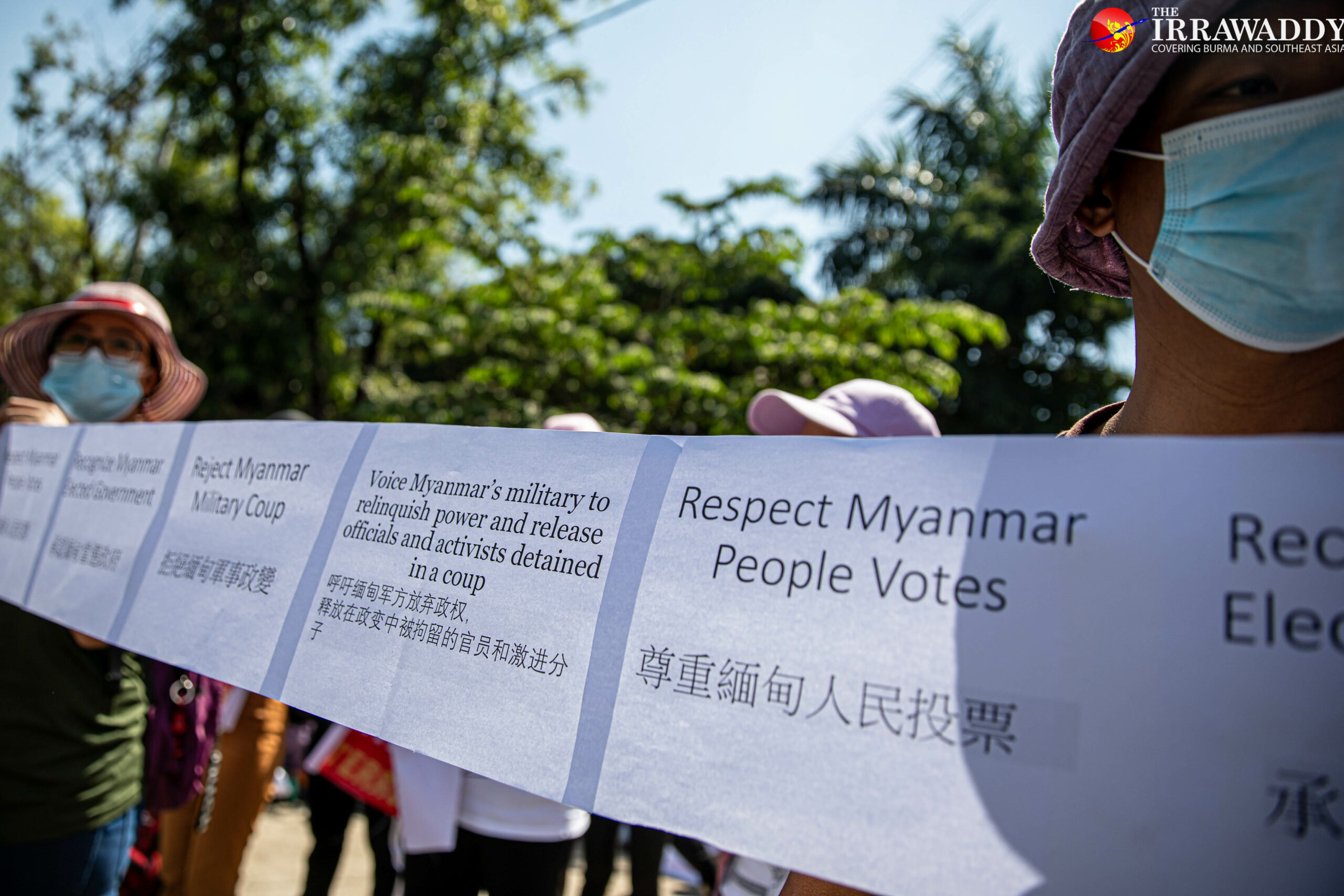

In February, weeks after the coup, U Kyaw Moe Tun surprised Myanmar people and foreign governments by denouncing the regime in an emotional address before the UN General Assembly, even flashing the three-finger salute that has become a symbol of the resistance.

Enter China, which since early August has lobbied to keep U Kyaw Moe Tun in his post while insisting that he not be allowed to address the UN General Assembly. Beijing’s approach to the ambassador issue is part of its complex and high-stakes diplomacy in post-coup Myanmar.

Soft approach

Soon after the regime ousted Myanmar’s elected government in February, China’s state-run Xinhua news agency described the seizure of power by force of arms as a “cabinet reshuffle” and did not condemn the coup.

Since then, anti-China sentiment in Myanmar has hit fever pitch due to Beijing’s failure to condemn the military crackdown and the mounting perception that it has fully sided with the junta.

Factories owned and run by Chinese companies have been attacked and China’s image has been shattered and will be hard to repair in the eyes of Myanmar citizens, who deeply loathe the military junta.

In February, amid growing anti-China protests in Myanmar, the Chinese ambassador came out to say that “the current development in Myanmar is absolutely not what China wants to see,” though, as is common with Chinese diplomatic statements, he left room for interpretation.

In August, China started calling the junta Myanmar’s “government” and pledged US$6 million to fund 21 development projects in the country.

China and the junta also pledged to continue the implementation of China’s strategic infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Myanmar. These

ambitious projects were outlined by China’s President Xi Jinping and first proposed to the NLD government ousted by the junta’s Feb. 1 coup.

Then on Aug. 25, a new rail line providing China with access to the Indian Ocean via Myanmar was opened on the Chinese side of the border.

The rail line stretches from Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan Province, to Lincang, a prefecture-level city in China’s Yunnan Province opposite Chin Shwe Haw, a border trade town in Myanmar’s northeastern Shan State.

Also in late August, Sun Guoxiang, a special envoy who served as China’s point man in Myanmar’s peace negotiations between the previous government and ethnic armed groups, met regime leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and other officials during an unannounced visit last week.

During the unpublicized visit, he also met with junta Foreign Affairs Minister U Wunna Maung Lwin and Minister for the Union Government Office Lieutenant General Yar Pyae.

During the weeklong visit, Sun reportedly asked Min Aung Hlaing for permission to speak to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to no avail.

At the end of the visit, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin said, “We will work together with the international community to play a constructive role in Myanmar’s efforts to restore social stability and resume democratic transformation at an early date.” At first glance, one would think it was a statement from the US State Department. It is easy to develop “statement fatigue” when following developments in Myanmar, but Wang’s reference to Beijing’s desire to “resume democratic transformation” raised more than a few eyebrows.

Then news emerged that China sought to continue working with the NLD and had reportedly expressed concern over the junta’s plan to dissolve the party.

Then, in early September, the NLD was invited to attend a summit for Asian political parties hosted by the Communist Party of China (CPC). This is a signal to the junta that the CPC continues to recognize the NLD. In doing so, China was in fact continuing an old policy.

In the old days, China backed the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) and provided arms, political support, thousands of volunteers and a clandestine radio station and allowed CPB leaders to stay in Beijing. On the border, fierce battles broke out between the China-backed CPB and the Myanmar military.

Meanwhile, China also maintained relations with the then socialist government led by dictator General Ne Win, who ruled the country from 1962 to 1988. The relationship was mostly stable, though Chinese and Sino-Myanmar citizens suffered through anti-China riots in Myanmar in 1967. As a result of the violence, the two countries called their ambassadors home. China downgraded its relations with the Ne Win government in favor of party-to-party relations with the CPB. Since then, China has deployed a two-pronged policy to exercise political leverage in Myanmar.

After the bloody coup in 1988, China turned the tables and supported the military regime known as the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC). China poured economic assistance, aid and military hardware into the regime in Myanmar. Beijing’s change of policy served its strategic interest in Myanmar, which was under Western sanctions; the isolated regime was increasingly drawn into China’s orbit.

From 2015 onward China forged a close relationship with the NLD, inviting then opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to Beijing, where Xi received her, and working with her government after the party won Myanmar’s election of that year.

Under the NLD government, Xi visited Myanmar in January 2020, signing multibillion-dollar infrastructure deals and hailing a new era in bilateral relations.

While it professes to follow a “non-interference policy” in Myanmar, China has long meddled in the country’s affairs. Today, China has influence over several ethnic groups including the powerful Wa army in the north. China also sees that the NLD and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi are key forces in the Burman-controlled parts of the country, and serve as a stabilizing force in the nation. Therefore, China is keeping all its options open in keeping U Kyaw Moe Tun at the UN. But for how long?

China has forged alliances with many of the various powerful forces in Myanmar, including the armed ethnic insurgents in the north and the NLD in the Burman heartland. It remains to be seen how China will handle its relations with the military and the junta going forward.

In July 2020, Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing publicly said that “strong forces” are supporting terrorists inside Myanmar. Subsequently, a military spokesman told the media that most of a cache of weapons seized at around that time were Chinese made, and that rebel groups had illegally acquired them from China. The generals were implicitly pointing the finger at a powerful neighbor, accusing it of providing support to certain insurgent groups in the country. Of course, they did not dare to name the country publicly, but it was clearly a reference to China.

Now, China’s support for the NLD and for keeping U Kyaw Moe Tun at the UN will no doubt anger Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing.

China today plays an increasingly complex diplomatic game in response to the changing political landscape in Myanmar. How China will keep its new and former allies, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, happy remains to be seen. In turmoil-plagued Myanmar, the many actors with which China has forged ties are not all on friendly terms with each other.

Whatever the case, all actors in Myanmar, including the military, will be very cautious in dealing with their powerful neighbor; they know that China’s policy on Myanmar will be based on its own interest.

You may also like these stories:

Rohingya Without Myanmar ID Not Being Given COVID-19 Jab: Junta

Myanmar Junta Troops Killed in Sagaing and Kayah

Myanmar’s UN Ambassador to Stay On: UN Sources