YANGON—Blessed with a strategic location between India and China in the center of Southeast Asia, as well as direct access to the Indian Ocean, Myanmar is a source of envy for neighboring countries.

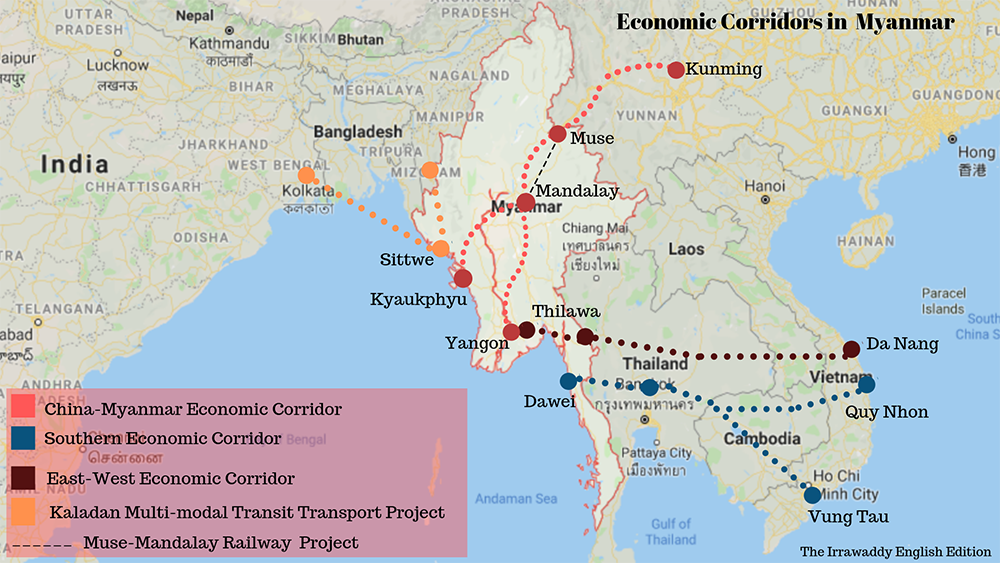

It should come as no surprise that the region’s most powerful players like China and Japan are competing with each other to establish three major South and Southeast Asian economic corridors in the country from the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean, while India is pushing for a cross-border transport system and sea route project with Myanmar. Make no mistake: None of those corridors would be complete without Myanmar due to its geographical importance.

In the meantime, from the country’s west in Rakhine, to the south in Yangon and Tanintharyi, north in Kachin, central region in Mandalay and areas on the Chinese border in Shan State, 10 mega-infrastructure projects worth billions of dollars that are related to these corridors and India’s cross-border project are on their way for Myanmar.

This has prompted speculation that the country seems to be gearing up to become the “last frontier” economic hub in the region. At the same time, experts warn, the projects pose risks to the country if the government can’t manage them properly.

Economic corridors

Currently, Beijing seeks to extend mega-infrastructure projects into Myanmar under the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), part of its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The 1,700-km CMEC runs from Kunming to Mandalay, then east to Yangon and west to the Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in western Rakhine State.

Within Japan’s grand plan, Myanmar sits on two major economic corridors: the East-West Economic Corridor connecting Vietnam’s Dong Ha City with Yangon’s Thilawa SEZ via Cambodia and Thailand, and the Southern Economic Corridor connecting central Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand to the Dawei SEZ in southeastern Myanmar.

India is also actively promoting its Act East Policy in Myanmar by implementing the Kaladan Multi-modal Transit Transport project. The ambitious Act East Policy aims to develop close, comprehensive ties in politics, economics and security through developing trade relations with the Mekong countries and other states surrounding China.

Ten Mega Infrastructure Projects in Myanmar’s Economic Corridors

Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone

Location: Bay of Bengal coast in western Rakhine

Highlights:

– A crucial BRI project

– $1.3-billion investment in the initial phase, with 70% from China International Trust and Investment Corporation Group (CITIC) and 30% from the Myanmar government

– 50-year concession, during which the Myanmar government will earn $7.8 billion in revenue from the SEZ and $6.5 billion from the deep seaport

– Gives China direct access to the Indian Ocean and allows its oil imports to bypass the Strait of Malacca

– Serves as the terminus for twin cross-border oil and gas pipelines between the two countries

– Includes a 1,000-hectare industrial park and deep seaports on Made and Yanbye islands. The park is expected to include facilities for textiles and garments, construction materials processing, food processing, marine supply and services, pharmaceuticals, electrical and electronics goods, and research. The deep seaports will have annual capacity of 7.8 million tons of bulk cargo and 4.9 million TEU containers.

Current status:

– Framework agreement signed in November 2018

– CITIC has hired Canadian company HATCH to oversee the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) and Preliminary Geological Survey for the project, which are now underway.

Dawei Special Economic Zone

Location: Andaman Sea coast, Tanintharyi Region in southern Myanmar

Highlights: Situated on the Southern Economic Corridor.

– Crucial for Japan’s Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) connectivity, which will link central Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand to southeastern Myanmar.

– Total investment of $8 billion for a 196-sq.-km deep seaport and industrial complex that is set to be Southeast Asia’s largest

– Thailand’s Neighboring Countries Economic Development Cooperation Agency (NEDA), Myanmar’s Foreign Economic Relations Department (FERD) and the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) are shareholders in Dawei SEZ Development Company Limited (SPV).

Current status:

– The Myanmar government is finalizing conditions precedent (CPs) with the concessionaires for the initial phase of construction.

– A fact-finding study by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) is under way based on NEDA’s existing master plan to ensure it is in conformity with changing political, economic and social conditions.

Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project

Location: Sea routes and a highway transport system to link the eastern Indian seaport of Kolkata with the landlocked northeastern Indian state of Mizoram through Myanmar’s Rakhine State in Sittwe and Chin State in Paletwa.

Highlights:

– A key element of India’s Act East Policy, which aims to develop close ties in politics, economics and security via trade relations with the Mekong countries and other states surrounding China

– Port facility in Sittwe to accommodate large cargo ships

– Port and transshipment terminal at Paletwa

– 130-km two-lane highway from Paletwa to the Myanmar-India border

– 100-km two-lane highway in India’s Mizoram State

Current status:

Private operator approved for Sittwe Port according to 2018 MoU between Myanmar and India

Muse-Mandalay Railway

Location: Muse, near the Chinese border in northern Shan State, and Mandalay in central Myanmar

Highlights:

– Forms the first phase of a strategic railway link that Beijing plans to build, with a parallel expressway, from Kunming to Kyaukphyu in Rakhine State, along with a separate road running through northern Myanmar, India’s northeastern states and Bangladesh under the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIM-EC).

– 268-mile-long railway with $8.9 billion investment

– Myanmar Railway and China Railway Eryuan Engineering Group (CREEG) signed an MoU last October to conduct a feasibility study.

Current status:

China handed over a feasibility report to Myanmar in April, and Myanmar will make final decisions on the specific details of construction by the end of this year.

Three Border Economic Cooperation Zones

Location: Along the Chinese-Myanmar border at Kanpiketi in Kachin, and Chinshwehaw and Muse in northern Shan State

Highlights:

– Construction of the three Border Economic Cooperation Zones in Shan and Kachin as part of the BRI was one of very first agreements the NLD made with China.

– Agreed by the Myanmar and Chinese governments when Daw Aung San Suu Kyi attended a BRI meeting in Beijing in 2017.

– Trade and processing, small and medium-sized industrial facilities, a trade logistics center and a quality packing center for agricultural products bound for export to China will be included.

Current status:

– China has nearly completed building infrastructure for the three locations. Myanmar has to conduct preliminary negotiations for relevant use of land and transportation. The two sides still need to negotiate the demarcation of borders areas.

Click the icons for more detailed information about the projects.

Myitkyina Economic Development Zone (aka Namjim Industrial Zone)

Location:

– The long, historic Ledo Road, 25 km from Kachin State’s capital Myitkyina

Highlights:

– A crucial, 4,700-acre project under the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor agreement

– $400 million investment; project includes nearly 500 factories and 5,000 buildings

– Kachin State government and Yunnan Tengchong Heng Yong Investment Company (YTHIC) are shareholders.

Current status:

– A master plan has been prepared and a feasibility study is in progress. Discussions on MoA and joint venture agreements are underway.

Mandalay Port Project

Location: On the bank of the Irrawaddy River, 1 km west of Mandalay

Highlights:

– 20-acre project with a new port with container storage, cargo warehouses, pier bridges, approach bridges and cargo-handling machinery

– To be implemented with a grant of more than 6 billion yen from the Japan International Cooperation Agency

Current status:

– The project will commence this year.

Myotha Industrial Project

Location:

– South of Mandalay International Airport in Mandalay Region. It lies in the center of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor.

Highlights:

– A 260,874-acre project combining agricultural land, ecological reservation land, educational facilities, residential areas and recreational facilities.

– Jointly developed by Mandalay Region Government and Mandalay Myotha Industrial Development Public Company (MMID PCL)

– Expected to generate 33,700 jobs

– Yunnan, China-based Techong Industrial Park Development Co. Ltd. agreed with MMID PCL to set up an urban industrial zone worth a total of $390 million on nearly 300 acres in the MIP last year.

Current status:

– Nearly three-dozen companies from China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Denmark and the Netherlands are already operating plants producing animal feed, concrete and other products.

Thilawa Special Economic Zone

Location:

Situated at the Yangon estuary in Myanmar’s commercial hub, Yangon.

Highlights:

– Backed by Japan; Myanmar’s first special economic zone

– Aims to improve connectivity between Bangkok and Yangon along Japan’s East West Corridor.

– A total of 108 companies—from construction to container to garment to automotive—from 19 countries had invested in the Thilawa SEZ as of June this year; over half of the companies are from Japan.

Current status:

– Phase 3 of the Zone B project is being planned for implementation.

Pathein Industrial City

Location: On the bank of the Pathein River, 4 miles south of Ayeyarwaddy Region’s capital Pathein

Highlights:

– A 6,700-acre project with industrial zones, a river port for cargo ships weighing 10,000 tons and commercial and residential areas

– Developed by Ayeyarwady Development Public Co. Ltd.

– Part of the CMEC project; as part of this, Hong Kong-based China Textile City Network Co. Ltd. plans to establish garment factories on 200 acres.

Current status:

Phase 1 of Zone A is being implemented; infrastructure is 60-percent complete.

Prioritizing economic infrastructure

After nearly six decades of isolation under military dictatorships, the government led by State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has been implementing economic reforms as part of Myanmar’s democratic transition.

The country is listed as having the worst infrastructure gap among the 50 nations covered in Global Infrastructure Outlook’s 2017 report, which said the country’s positive economic trajectory will be challenged by its massive infrastructure needs.

Aware of this situation, the NLD government’s 12-point economic policy favors prioritizing the rapid development of fundamental economic infrastructure such as electricity generation, roads and ports. Rather than a long-term economic vision for the future, the policy focuses on taking advantage of “potential opportunities” by identifying changing and developing business environments in ASEAN and beyond.

U Thaung Tun, Myanmar’s Minister for Investment and Foreign Economic Relations, said in January that infrastructure is one of the biggest challenges that the current government faces. But he said the country can take advantage of its strategic location at the intersection of two of the world’s most important emerging markets, China and India.

Click the icons for more detailed information about the projects.

Will Myanmar benefit?

Given their size and connectivity, the 10 infrastructure projects in the three corridors, along with India’s cross-border projects, will likely solve the problems to some extent.

The government has drawn up the Myanmar Sustainable Development Plan (MSDP), the aim of which is to align the country’s numerous policies and institutions to achieve genuine, inclusive and transformational economic growth. The MSDP also aims to improve the country’s connectivity with neighboring countries and prioritizes economic corridors under both the GMS and BRI.

Experts predict the major infrastructure projects will enable Myanmar to become a pivotal hub in the region, improving trade, foreign investment, and the living conditions and incomes of its citizens. But

there is a risk that the projects will cause social and environmental harm and provoke conflicts in ethnic areas, and balancing the demands of powerful nations will be difficult.

Thitinan Pongsudhirak, an associate professor at the Institute of Security and International Studies in the Faculty of Political Science at Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University, told The Irrawaddy that Myanmar’s role as a potential regional hub is completely in line with the rise of the Indo-Pacific, which is overtaking the Asia-Pacific as the main geostrategic framework for regional relations.

However, he said: “Domestic political instability, particularly persistent internal conflicts, may derail and undermine these projects,” referring to the country’s ongoing fighting between ethnic armed groups and government troops, as some project areas are in ongoing conflict zones in Rakhine, Kachin and northern Shan states.

He suggested that the growth and development from these projects would have to be managed so that inequality narrows while abject poverty recedes.

“What Myanmar does not want is a lot of growth and development and worsening inequality across ethnic and geographical divides, with the rich getting richer and the poor no better off, while ethnic conflicts are exacerbated,” he added.

Jonathan Hillman, director of the Reconnecting Asia Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), told The Irrawaddy that despite Myanmar’s significant potential, megaprojects are inherently risky, especially when it comes to China, which originated at least half of the 10 mega infrastructure projects.

He pointed out that much Chinese financing is tied to using Chinese contractors, which can reduce local economic benefits. Transparency will help to minimize cost inflation, he said.

“Ultimately, a lot hinges on not only selecting the right projects, but applying appropriate safeguards when carrying them out. Environmental damage, for example, can undercut a project’s potential benefits,” he added.

Thitinan warned that those projects could also make Myanmar more beholden to and dependent on China, meaning Myanmar will have a harder time maintaining a balance among the major powers, especially among China, India and the US.

Historian Thant Myint-U suggested that Myanmar first needs to have its own vision of the kind of economy it wants in 10 or 20 years’ time, and then think of the infrastructure it will need, both internally and in connection with neighboring countries.

He said it’s important to consider these projects in environmental and geopolitical terms, as well as the impact they may have on inter-ethnic relations or internal armed conflicts.

“However, the starting point should be a discussion about the political economy Myanmar wants to have—what will drive Myanmar’s own industrial revolution and what kind of industrial revolution is possible in the mid-21st century? How important is equality versus growth? These are the questions that must be answered before any big infrastructure projects are considered.”