Few would dispute that Myanmar’s current borders are outcomes of British colonial policies and conquests and so cut through areas inhabited by the same ethno-linguistic groups. Formal links between those groups were severed while informal contacts continued as before, and still do, which has been an issue for all post-independence governments. And did India, as some Indian commentators claim, hand over territory to the then Burma [the country’s name until 1989] in the 1950s? Disaffection and misunderstandings of what was agreed upon when independent Burma held talks and signed agreements with its neighbors have led to myths and conflicts that never seem to go away.

The border between colonial Burma and China was never clearly demarcated, mainly because several outlying frontier areas were too remote and, in many cases, almost inaccessible. Some were even designated as “unadministered”. It was not until January 28, 1960 that Beijing and Yangon signed a treaty delineating most of the common border. A complete border agreement was signed on October 1, 1960 and demarcated on the ground in 1961. The now 2,129-kilometer-long frontier was marked with stones showing numbers and text in Burmese and Chinese.

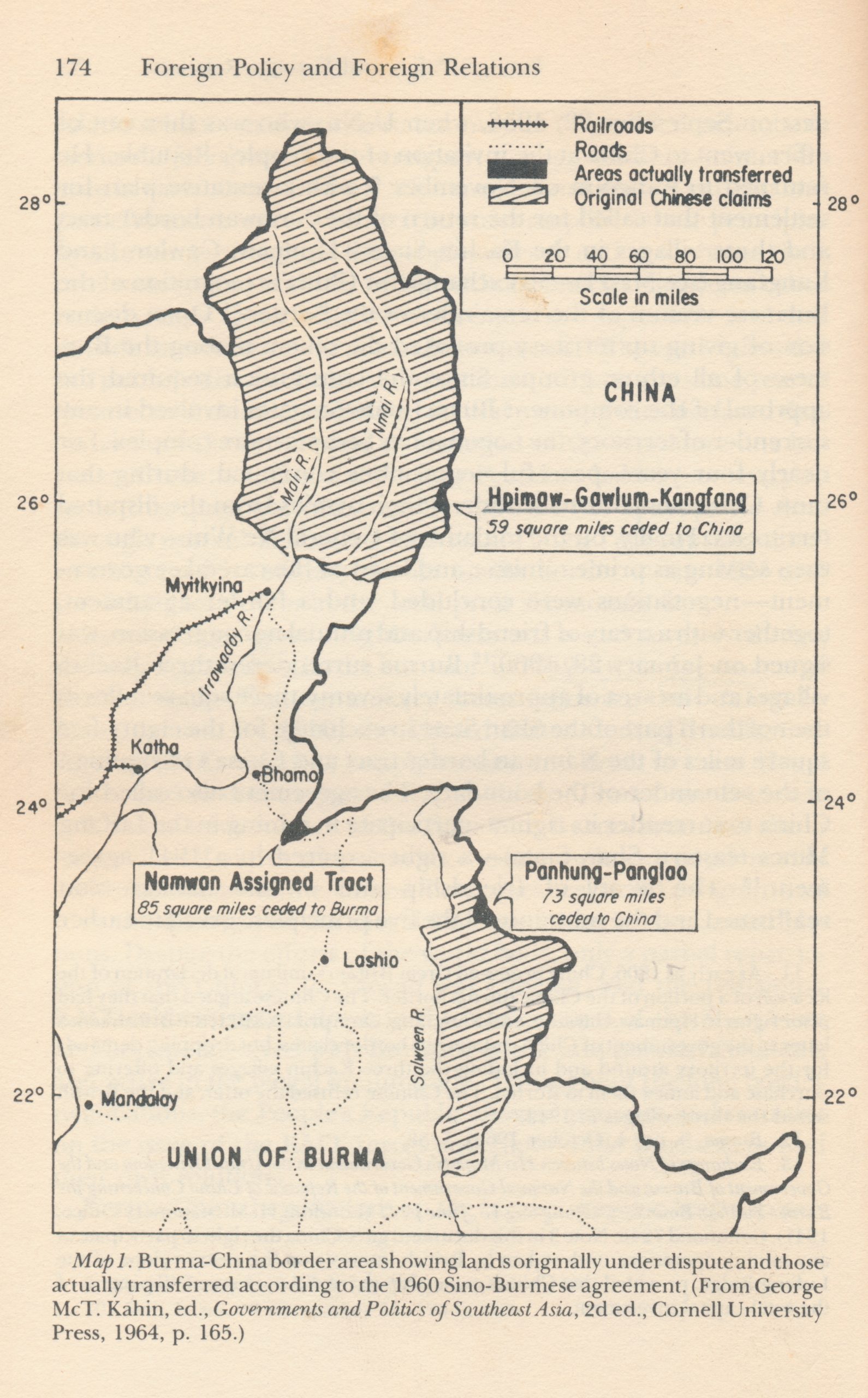

As part of the deal, a 153-square-kilometer-large area on the border was ceded to China. It contained the three small Kachin villages of Hpimaw, Gawlum and Kangfang, nothing more. In exchange, China recognized Burmese sovereignty over a 220-square-kilometer area northwest of Namkham known as the Namwan Assigned Tract, which the British had leased from China in 1897. The road from Namkham to Bhamo ran through it, and that was why the colonial power wanted to control that particular area. In essence, if not formally, the Namwan Assigned Tract became part of British Burma. The 1960 border agreement settled that issue.

China also gave up all its traditional claims to northern Kachin State. China never controlled that part of the country, which came under colonial administration in the late 19th century. Before then, those mountains were ruled by Kachin chieftains who paid allegiance to nobody. Even so, old Chinese maps showed the border at the confluence of the Mali Hka and Nmai Hka rivers and then along the crest of the Kumon Range up to the Chaukan Pass on the border with India. Now China agreed to draw a more realistic map, showing the entire Kachin State as part of Burma.

The 1960 deal with China was not unfair by any international standards. But rumors soon spread across Kachin State to the effect that vast tracts of Kachin territory had been ceded to China by prime minister U Nu and his Kachin political ally, the Sima Duwa Sinwa Nawng. Even today, it is not unusual for many Kachins living on the Myanmar side of the border to point at an adjacent Kachin-inhabited area in Yunnan Province and claim it as a piece of land given to China by those two men. The failure of the central government to clarify the nature of the border agreement was at the root of misunderstandings which drove hundreds of young Kachin underground.

Another, more tangible reason was that U Nu wanted to make Buddhism the state religion, a move seen by the predominantly Christian Kachin as an open provocation. On February 5, 1961, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) was formed in Kachin-inhabited areas of northern Shan State. Since then, the KIA has grown into one of the country’s best-organized ethnic armed organizations (EAO) with thousands of well-armed, battle-hardened soldiers. When the KIA came under heavy attack by the Myanmar military in 2012, thousands of Kachin people living in China came up to the border to show solidarity with their brethren on the other side. The KIA has benefited from that cross-border solidarity in many other ways as well.

A misunderstanding similar to that among the Kachin about the location of the official border also exists in the Wa Hills of Shan State. Without questioning the claim, the International Crisis Group wrote in a report dated September 21, 2010 and titled China’s Myanmar Strategy: Elections, Ethnic Politics and Economics: “Many Wa consider themselves more Chinese than Burmese. They feel that China…abandoned them during the border negotiations in the 1950s, when Beijing ceded border territories to please the Myanmar [Burmese] government and break China’s international isolation.”

But China did not cede any territory to Burma, either “in the 1950s” or under the terms of the 1960 border agreement. The Chinese gave up their old claims to the Wa Hills, which they, as was the case with northern Kachin State, had claimed but never controlled. And, like in Kachin State, it was Burma which, in exchange for the Chinese giving up their claims, ceded a small piece of land to China: the 189-square-kilometer Panhung-Panglao area in the northern Wa Hills. Like Hpimaw-Gawlum-Kangfang, Panhung-Panglao was a small village tract in a remote, sparsely-populated corner of the country.

It could also be argued that the Wa Hills have never been controlled by any central government. During the colonial era, the government presence was confined to occasional flag marches up to the Chinese frontier. The British sent soldiers with a flag which was planted where the colonial power thought the border with China should be. Many Wa lived on the other side in what was formally Chinese territory. But no central government in Beijing exercised any control worth mentioning over that area until the mid-1950s, when Mao Zedong’s communist government sent its army to secure the rugged mountains in southern Yunnan. Until then, the Chinese Wa Hills and some other adjacent frontier areas had been virtual no man’s lands.

On the Burmese side, it was only late in the colonial era that Möng Leun, the largest and most developed of the Wa principalities, established closer relations with the rest of the country — which means the neighboring Shan states — and a colonial officer was sent from Yangon to liaise with the local prince. In the years after independence in 1948, nationalist Chinese Kuomintang forces sought refuge in the Wa Hills following their defeat in the Chinese civil war. They, and numerous local warlords, ruled the Wa Hills and some adjacent parts of Shan State throughout the 1950s and most of the 1960s.

Then, in the early 1970s, the Wa Hills in Burma were taken over by the China-backed Communist Party of Burma (CPB) and, after a mutiny among the predominantly Wa rank-and-file of its army in 1989, the CPB’s mainly Burmese leaders were driven into exile in China. The mutineers formed the United Wa State Party and Army (UWSP/UWSA) and began to rule the Wa Hills as their own state. The Wa have their own government, local administration, schools, hospitals, courts — and Burma’s biggest EAO. The UWSA fields an estimated 20,000 troops equipped with modern weaponry, including anti-aircraft guns, surface-to-air missiles, heavy artillery, weaponized drones and armored vehicles, most of it procured in China. Historical twists and turns have created a self-governing buffer state between Myanmar and China, one which officially belongs to Myanmar but has much closer contacts with China. Not surprisingly, several of the UWSP/UWSA leaders were born on the Chinese side of the border.

The delineation and later demarcation of Myanmar’s 1,643-kilometer-long border with India is also rooted in the legacies of colonialism and, therefore, rife with misunderstandings. One concerns the Kabaw Valley, a highland area in western Sagaing Region opposite the Indian state of Manipur. It is a widespread belief among people in Manipur that the valley rightfully belongs to them. According to the popular Manipuri website E-Pao: “There are now so many questions in the minds of the people of the state of Manipur as to why, how and on what pretext, such a vast expanse of land known as Kabo [Kabaw] Valley was given away to the Burmese by the then Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru. Kabo Valley is the ‘Jewel of Manipu’’, in the same line as when Nehru said, ‘Manipur is the Jewel of India’.” This, according to E-Pao, happened “on 13 January 1954” and it was done “without the consent of the people of Manipur.”

Brahma Chellaney, a prominent and prolific Indian commentator, presented another version in an article for the Asian Age on April 7, 2007. The alleged handover, Chellaney stated, took place a year earlier: “A sore point in Manipur remains the way Nehru unilaterally accepted Burmese sovereignty over the 18,000-square-kilometre Kabaw Valley in 1953.” A third version was presented on the Manipuri blogsite exmeitei on November 28, 2018: “In 1952, India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru completely gifted the Kabaw valley to the Myanmar [Burmese] government as a token of peace without the consent of natives living there nor the Ninghthouja dynasty [the royal family].”

In reality, however, no such handover occurred in 1952, 1953 or 1954. As any serious historical study would show, the Kabaw Valley, which in pre-colonial days had changed hands between the rulers of Manipur and Burma, finally became part of the then Burmese kingdom on January 9, 1834. The border, with the Kabaw Valley on the Burmese side, was known as the Pemberton Line after Boileu Pemberton, the British commissioner who negotiated the deal. On January 25, 1834, another agreement was signed which stipulated that the king of Manipur would be compensated for the loss of the valley. No map from the colonial era and later would show the Kabaw Valley as part of Manipur. The validity of colonial agreements and how they came about can always be questioned, but the fact remains that the Kabaw Valley has been within the boundaries of Burma for nearly 190 years. Nehru never handed over the Kabaw Valley or any other any Indian territory to Burma.

On March 10, 1967, India and Burma signed the first agreement that delineated the entire common border. According to a May 15, 1968 study of the issue by the US State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research: “Numerous earlier treaties and acts have affected the alignment of portions of the boundary and form much of the basis of the new act.” In other words, there were no major changes to what had been referred to as the “the traditional line” were made. The precise location of the border that was now being formalized was unclear at some places, so adjustments were made and new border stones were erected.

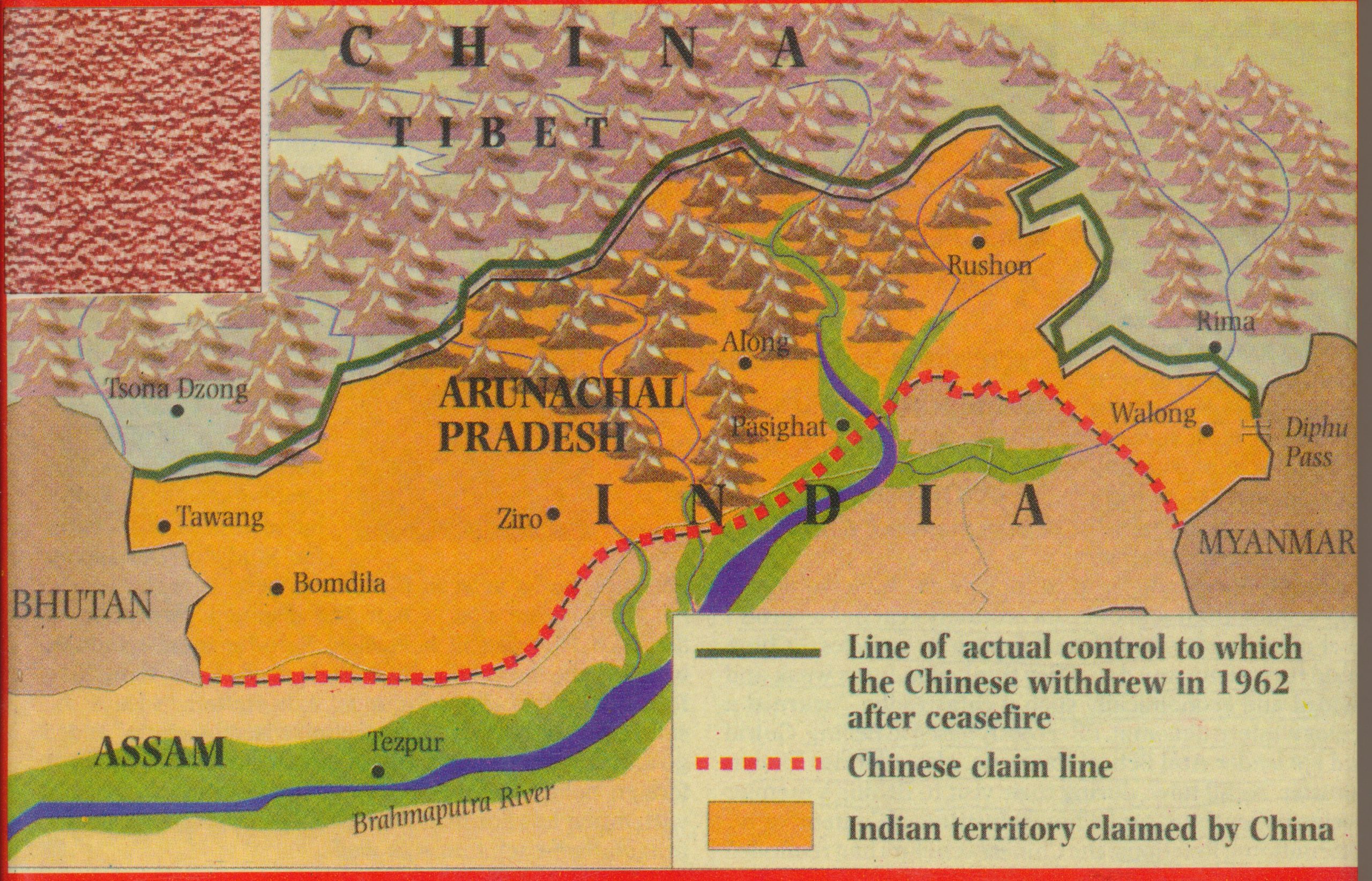

The only problem, which remains a thorny issue in Indo-Burmese as well as Sino-Burmese relations, is the demarcation of the border between Myanmar and the north-eastern corner of the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. China lays claim to most of Arunachal Pradesh, calling it “South Tibet”, and that includes the area at the border between China’s claim and the line of actual control that separates India from China. The two countries fought a bitter war over control of what today is known as Arunachal Pradesh in 1962, and some of the fiercest battles took place near Walong in that particular part of Indian-administered territory. The 1968 US study stated: “Chinese claims to Indian territory in the North East Frontier Agency [now Arunachal Pradesh], however, have cast a shadow on the location of the northern terminus of the Burma-India border.”

Therefore, it is not unusual to see different figures for the total length of the border between India and Myanmar, but it is an issue that is never discussed when Burmese and Chinese officials meet because it would force Myanmar to take sides in the border dispute. If Naypyitaw recognized the entire length of its border with India, the Chinese would protest and argue that the northernmost stretch of the border is with their “South Tibet.” A new, more aggressive view was presented by Zhou Bo, a retired Chinese army colonel, in an interview with the BBC on March 9: “The entire Arunachal Pradesh [state], which we call southern Tibet, has been illegally occupied by India — it’s non-negotiable.” China has never before claimed “the entire Arunachal Pradesh” as theirs, and if that is official policy, it would put Myanmar in an even more precarious situation in its relations with India as well as China.

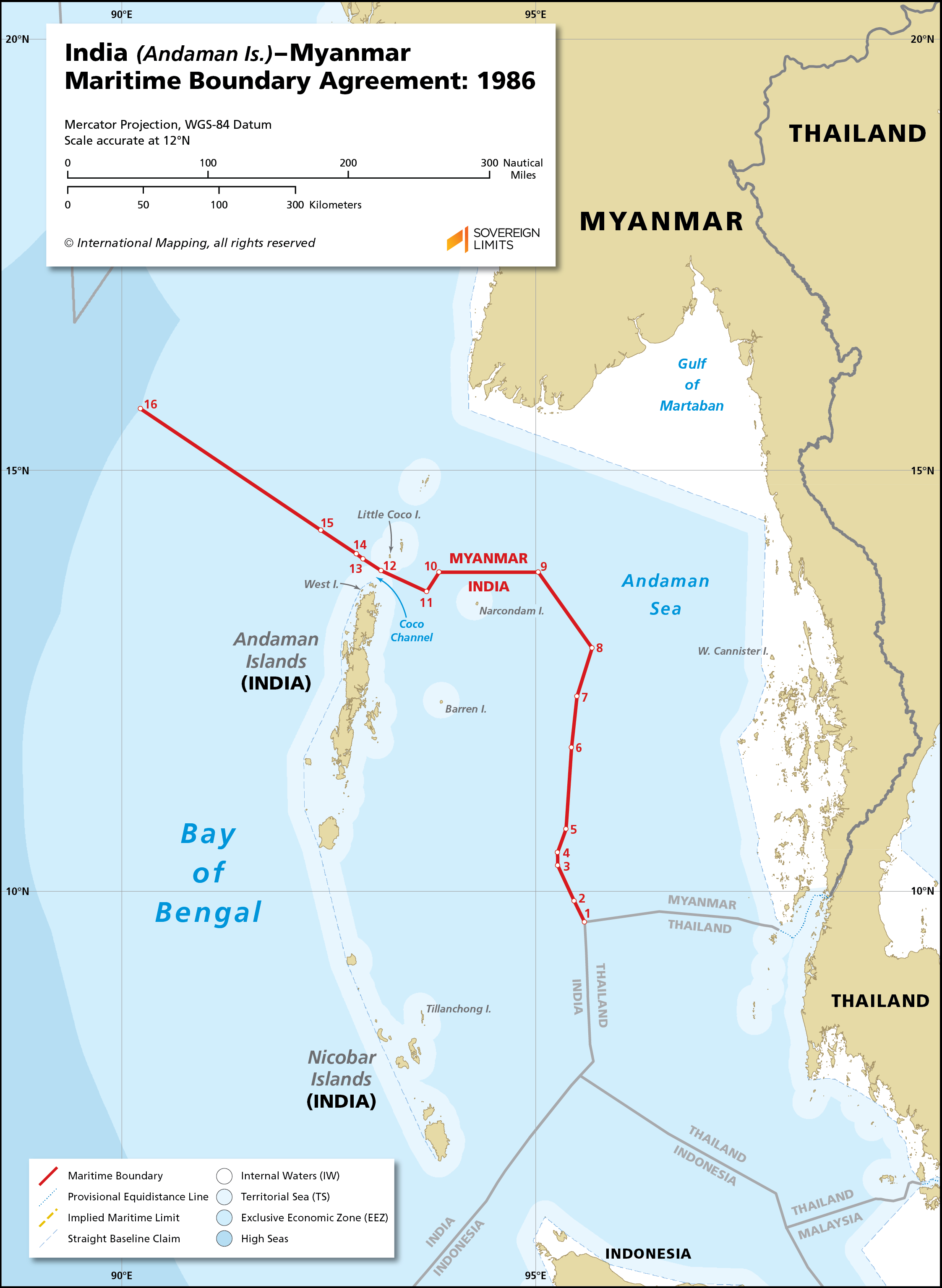

Myanmar also has a maritime border with India which runs through the Andaman Sea and separates India’s Andaman and Nicobar Islands from Myanmar’s Coco Islands. Once again, Chellaney presents an entirely incorrect account of a territorial issue that involves Myanmar and India. He stated in a paper presented at a Myanmar conference in Stockholm, Sweden, in May 2008 that China’s security agencies “operate electronic-intelligence and maritime-reconnaissance facilities on the two Coco Islands in the Bay of Bengal. India transferred the Coco Islands to Burma in the 1950s, and Burma then leased the islands to China in 1994.” Similar claims have appeared on numerous Indian websites, but historical records suggest otherwise. Australian Myanmar scholar Andrew Selth wrote in a detailed and very comprehensive study titled “Burma’s Coco Islands: Rumours and Realities in the Indian Ocean” that the British colonial authorities in Calcutta transferred jurisdiction from private entrepreneurs on the Coco Islands, which at that time had little more than a lighthouse on them, to British Burma in 1882. Burma became a province of India in 1886, but that did not change the status of the islands. When Burma was separated from India in 1937 and became a separate colony, the Coco Islands — Great Coco, Little Coco and a few surrounding smaller islands — remained Burmese territory.

Since independence in 1948, the Coco Islands have also belonged to Myanmar, and, Selth writes, “administered as part of Hanthawaddy District in Pegu Division, but during the 1970s control was passed over to the newly-created Rangoon Division.” In the 1960s and early 1970s, the main Coco Island was used as a penal colony for political prisoners, most of whom were members of the outlawed CPB and other leftist organizations. The exact position of the maritime border between India and Myanmar was established through a bilateral agreement that was reached on December 23, 1986.

So what about the alleged lease of the islands to China? That is also false, and an assumption based on a gross exaggeration of what happened in the 1990s. At that time, Chinese experts helped the Myanmar navy modernize and upgrade its bases, which included installing radar equipment on a number of islands. Chinese naval personnel were also present for a while showing their Burmese counterparts how to operate the fast-attack, missile-equipped Houxin and Hainan class vessels and other naval ships that Myanmar had acquired from China.

But there is no evidence to suggest that Chinese naval personnel are or ever were permanently based in Myanmar, or that China has some kind of military base there. The only thing that can be said with certainty is that the intrusions of China’s naval vessels, including submarines, have become increasingly common in the Indian Ocean, including the Bay of Bengal. It is also possible that Beijing may benefit from the intelligence information which is picked up by the Chinese-supplied radar systems on some of Myanmar’s naval bases, including the facilities on the Coco Islands. Those rumors have resurfaced after a website run by the London-based policy institute Chatham House published an article on 31 March about new construction on the islands.

China’s presence in the Indian Ocean is a new development which could lead to conflicts with other powers in the region. India considers the Indian Ocean “its lake” and its powerful navy patrols it from numerous bases on the country’s coasts — and the Andaman Islands near the Coco Islands. The United States military has a huge base on Diego Garcia, an island in the British Indian Ocean Territory, Britain’s last and only possession in the region. Washington leases Diego Garcia from Britain and the base played an important role in both Golf Wars and US combat operations in Afghanistan.

Thousands of US troops are stationed on Diego Garcia, which also houses sophisticated radar, space tracking, and a communications facility. It has also been used for long-range bomber operations and the replenishment of nuclear-powered submarines. The French maintain a significant military and military-related presence on their Indian Ocean islands Réunion and Kerguelen. Australia controls two Indian Ocean island territories, Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands [not to be confused with Myanmar’s Coco Islands]. The 2016 Australian Defense White Paper stated that the airfield on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands will be upgraded to support Australia’s maritime patrol aircraft, possibly as part of a plan to enhance security in the Indian Ocean region. And China has established its first overseas military base in Djibouti on the Horn of Africa and the gateway to the Red Sea and the Suez Canal.

Tensions are rising in the region, along Myanmar’s borders, in the Himalayas, and in the Indian Ocean. But all this also means that regional security has to be analyzed properly without depending on myths, misinformation and wild exaggerations. Colonial legacies may complicate matters, but it is clear that the Coco Islands and the Kabaw Valley have been Burmese since the 19th century, and remain so today. There are no Chinese bases in Myanmar, only naval bases that have been upgraded with China’s assistance and Beijing’s security agencies may or may not have access to intelligence information the Myanmar navy picks up from the bases. And the borders between Myanmar and China and Myanmar and India were demarcated in the 1960s without any major transfers of territory.

What is happening on the Coco Islands?

According to what can be gleaned from Google Earth, the runway on Great Coco has been lengthened from 1,300 meters to 2,300 meters. In January this year it was widened as well and two new hangars have been added. According to Chatham House’s report of 31 March, “Is Myanmar building a spy base on Great Coco Island?”, “The width of the hangar appears to be close to 40 meters, limiting the aircraft that it may eventually accommodate but opening the possibility for high- performance aircraft to be stationed there.”

New buildings have also been spotted north of the airport beside a radar station and what appears to be a newly-built pier. There is also a new causeway connecting the southern tip of Great Coco to the much smaller Jerry Island, “indicating the future extension of Great Coco facilities.” Missing from the Chatham House report are new constructions on the uninhabited, densely forested Little Coco: a huge building in the middle of the island, a road to the coast, and two new helipads.

It is not impossible that much of the equipment for all those construction projects and facilities are of Chinese origin and that China may have an interest in monitoring this strategically important maritime area. But it could also be part of junta chief Min Aung Hlaing’s paranoia: he sees enemies everywhere and is doing what he can to protect the country from any kind of attack that he imagines poses a threat to his power. Whatever the case, only time will tell.