YANGON — Outside a drab concrete compound in central Yangon, a short walk from the looming gold spire of Shwedagon Pagoda, dozens of young men and women huddle in the shade waiting their turn.

They have all come to the One Stop Center (OSC), the private business Kuala Lumpur has hired to process the visa applications of the thousands across Myanmar who come here each month with dreams of turning their lives around in Malaysia’s booming factories, construction sites and stately homes. Well over 100,000 of them are in Malaysia already.

But getting there is not cheap. And since Malaysia outsourced the visa process to a handful of homegrown companies and their partners abroad a few years ago, it has gotten far more expensive.

Visa applications that used to cost $6 are now nearly 10 times that much. A health check that once cost $10 to $20 now costs $56.

The new fees come on top of the hundreds of dollars the workers pay employment agencies to find them the jobs. As few can afford it all, most take on crippling loans that drive them into debt bondage and what labor rights groups call a prime example of modern-day slavery.

Outraged by the new fees, Nepal abruptly banned its workers from going to Malaysia in mid-2018. Within months, Malaysia signed a new deal with Nepal promising that the employers in Malaysia would cover the fees and all other recruitment costs, though the details are still being worked out. In September, Malaysia itself banned migrant workers from Bangladesh following media reports that a handful of firms had monopolized the system and raised prices.

In December, Malaysia’s human resources minister, M. Kulasegaran, told The Star, a local paper, that his government was negotiating similar deals to the one it struck with Nepal with Bangladesh, Indonesia and Vietnam.

The minister made no mention of Myanmar, which sends far more workers to Malaysia than Vietnam and where the same few Malaysian companies hired to run the country’s visa process continue to funnel cheap labor through the pipeline at the workers’ expense.

The company at Myanmar’s end of that pipeline, Diamond Palace, is run by a former Myanmar Army officer, U Thein Than, who cornered the market just before the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party was swept from power in the 2015 general election. The company’s own employment agency is currently barred from sending migrant workers abroad because it was overcharging them.

Andy Hall, a migrant worker rights specialist in Southeast Asia, said the “syndicate” of companies has created a “systemic situation of debt bondage for the workers, who take out high interest loans or have to mortgage and sell their land.”

Once in Malaysia, he said, the workers usually have their passports confiscated and find it nearly impossible to leave abusive conditions, “thus creating a situation of systemic forced labor.”

Hall said the hundreds of dollars Malaysian employment agents charge their counterparts abroad to pass on job opportunities — and often partly kick back to the employers offering them — has plagued the system for years. The new fees the works now have to pay, he continued, “only further add [to] the costs borne by them.”

Pay to play

Malaysia has long leaned on an army of millions of migrant workers to fuel its economy. As of January, about 114,000 of them were from Myanmar, a near tie with India, according to Malaysia’s Immigration Department. Only Indonesia, Nepal and Bangladesh send more. Vietnam is a distant eighth with about 20,000 workers in the country.

But the real numbers are likely far higher given the many migrants believed to be working in Malaysia illegally. In 2017 Myanmar’s Labor Ministry said more than 420,000 nationals were working in Malaysia.

Among those hoping to join them and waiting outside the Yangon OSC one recent morning was Aung Khan, ashy 21-year-old ethnic Shan with a wisp of a beard and an A.C. Milan football jersey paired with his longyi.

“There are no jobs in Shan State,” he said. “I’m going [to Malaysia] to make money.”

Most of Myanmar’s migrant workers head for Thailand, a relatively easy trip across the border. The agent and visa fees are lower and the bureaucracy simpler. Those like Aung Khan with their eyes set on Malaysia put up with the added costs and paperwork for the promise of higher wages.

He was waiting for his agent to arrive and usher him into the OSC, where he will queue up at a series of windows to file his visa application forms and pay the prescribed fees while a TV plies him with a loop of gilded scenes of Malaysia more akin to a tourism spot than a job ad.

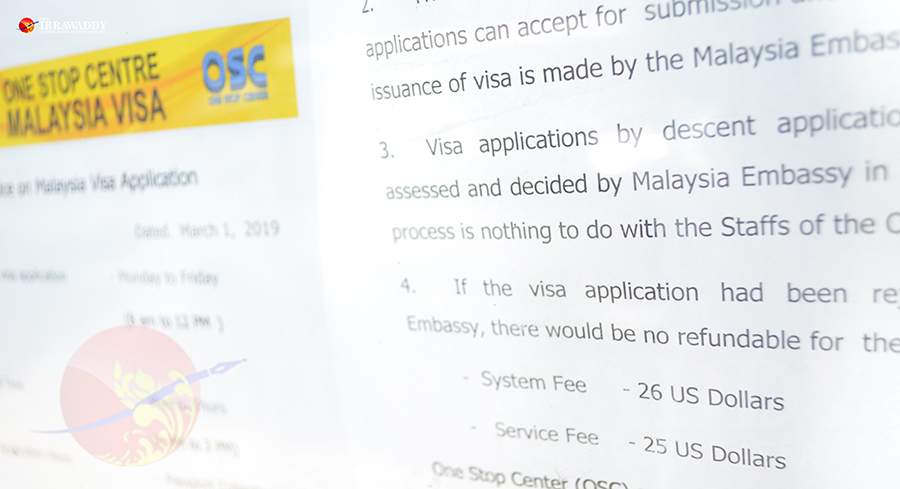

Before the OSC opened in December 2015, migrant workers headed for Malaysia paid only $6 for a visa at the Malaysian Embassy just around the corner. The OSC has forced them to pay much more. Now, besides the visa fee, they also have to pay a $25 service fee, a $26 system fee and a $26 immigration security clearance (ISC) fee.

Employment agencies say the $56 workers must now pay for pre-departure health checks, which include blood and urine tests, is also far higher than before. And while the workers used to have their pick of clinics across Myanmar, they now have to choose from one of only four approved by Bestinet — the Malaysian company the government of Malaysia hired to screen all prospective foreign workers for health problems before they arrive — all of them in Yangon.

The new fees, unique to Malaysia, have added painfully to the hundreds of dollars the workers were already paying employment agencies to land them jobs in Malaysia. The agencies say they can legally charge Malaysia-bound workers up to $850, and that about half of it goes to employment agencies in Malaysia for the “demand letters” they need from employers to place the workers in those jobs.

The agencies said their counterparts in Malaysia also insist on being paid through the “hundi” system, an informal, centuries-old practice of moving money across borders based on personal relationships that operates in a legal gray area. It keeps the payments beyond the reach, and out of sight, of either government.

“If you do not pay the money, you do not get the demand letter,” said the head of one employment agency in Yangon, who asked to remain anonymous for fear his business might suffer for speaking out.

Aung Khan said his parents had to take out a loan to pay for it all. They have already paid his agent 500,000 kyats ($329) and expected to pay him much more by the time they were done.

“I am sad they had to go into debt,” he said.

The $850 agencies can charge is well over half the per capita gross national income in Myanmar, and far more for the roughly one in three who live in poverty, whose ranks disproportionately make up those seeking work abroad.

When migrant workers and their families take on those levels of debt, the workers “almost definitely” end up falling into debt bondage, said Adrian Pereira, executive director of the North South Initiative, a non-government rights group based in Malaysia.

He said the risks were especially high when the employers take on the workers’ debts themselves and use their wages to pay themselves back.

In the most extreme cases, Pereira said, workers have been held for ransom to force their families to pay the lenders back.

Even when the employers do not take on the debt themselves, they have often had to pay the agencies to find the workers, he added, “so they don’t let go of the workers very easily” and make it almost impossible to leave the job.

Money for ‘nothing’

Critics of the new fees say they amount to little more than a cash grab by the companies that landed the government contracts to run the system.

In 2017, Stephen Sim, a then-opposition lawmaker in Malaysia whose party is now part of the ruling coalition, told Al Jazeera’s “101 East” current affairs program that the companies were getting paid for mere “paper shifting.”

Employment agencies in Myanmar see no good reason for the new fees, either.

“It’s not necessary; it’s just a money-making process,” said the head of another Yangon employment agency, who also asked to remain anonymous. “The OSC takes the money for doing nothing.”

“This is very expensive for the worker. Those machines are not the very high technology,” he said of the equipment the OSC and clinics use, taking particular exception to the new health check fees. “The $56 is just to register your name, to send to the Malaysia side. They send to the Bestinet company. $56 is only for that.”

U Kyaw Htin Kyaw, a spokesman for the Myanmar Overseas Employment Agencies Federation (MOEAF) and a member of its executive committee, said the agencies add the new fees to each worker’s final bill but make no money off the added costs themselves.

“All this money we put on the worker’s head, so the worker pays more,” he said, “So who will get the problem? The workers get the problem only.”

U Kyaw Htin Kyaw also said that the OSC, which quotes its fees in U.S. dollars, only accepts kyats but inflates the going exchange rate by 10 to 20 kyats on the dollar to further boost its profits.

“He is like a crocodile,” he said of the Diamond Palace boss. “His mouth is always open.”

Diamond Palace’s own on-site money change counter quotes the center’s rate for each day. On a recent morning that Diamond Palace was selling U.S. dollars for 1,524 kyats at the OSC, a popular money change counter downtown was selling for 1,512 kyats. The Central Bank of Myanmar’s reference exchange rate for the dollar that day was 1,514.9 kyats.

When the OSC opened, the MOEAF implored the Labor Ministry to shut it down, to no avail.

“At that time we rejected OSC; we did not want OSC,” U Kyaw Htin Kyaw said. “We wanted to strike in front of the office, but the government did not allow.”

Since December, when Reuters reported that some migrant workers in Malaysia were clocking long hours past the legal overtime limit at factories for Top Glove, the world’s largest glovemaker, to clear their debts, a few agencies in Myanmar have been advertising jobs in Malaysia with employers willing to cover all fees.

But U Kyaw Htin Kyaw, who runs an agency himself, said those employers remain the exception to the rule.

The men and women The Irrawaddy spoke with outside the OSC all said the fees were still on them, and all but one said they were going deep into debt to pay them.

Ko Kyaw Swe Oo, 34, from Irrawaddy Region, said he borrowed 300,000 kyats ($197) at 7 percent interest from a local moneylender to pay his agent and was told he would have to pay another 700,000 kyats ($461) soon.

“Farming is not good in my village and I can’t make as much money as before,” he said, complaining that the price of fertilizer was on the rise but his revenues were not.

He said his brother was already working in Malaysia and told him the pay was good. He was hoping to land a construction job in Kuala Lumpur but worried about what might happen if he fails, or if he ends up earning less than he expects.

“I’m worried that if I don’t get the job, or if I don’t earn enough money, I will stay in debt,” he said.

Blacklisted

Employment agencies in Myanmar blame the Yangon-based firm co-managing the OSC, Diamond Palace, for the new fees at least as much as the companies running the labor pipeline from Kuala Lumpur.

On its website, the Diamond Palace Group of Companies presents itself as a sprawling conglomerate with its hands in everything from military training to hotel management and road construction, an international trader of anything from beans to diesel, and a miner of tin, tungsten and lead. It calls itself a “pioneer in the IT field of biometric identification” and offers a weapons-tracking system that promises to reduce workloads with “zero error.”

Diamond Palace Services, a subsidiary, says it has been an exclusive service provider to Myanmar’s Foreign Affairs Ministry since 2013, running visa and consular services for the country’s embassies in China, France, Italy, Japan, Malaysia and Singapore. It says it has been operating the OSC in Yangon since 2015 with its Malaysian partner, Bukti Megah.

But for all its online boasting and highbrow tech talk, the website could use an update.

The company address it provides is an empty, overgrown yard — the property owner, who runs a hotel next door, says it has been vacant for years. Multiple calls to two listed phone numbers were never answered. A message sent to its listed email account was kicked back with an “address not found” error.

Staff at the OSC reluctantly directed The Irrawaddy to an unmarked office down a dim, dusty hallway in a shabby old building near the southeast end of Inya Lake. Inside, the few staff on hand confirmed that the sparse rooms were the national headquarters of Diamond Palace. They provided a phone number for the OSC’s general manager, Daw Thu Zar Mon, who said Diamond Palace would not be answering any questions and ignored all further messages.

U Myint Thu, permanent secretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said the ministry “terminated cooperation” with Diamond Palace in December and that its duties at the embassies were transferred back to embassy staff. He declined to say why or to comment further about the company.

“No more questions,” he said.

The Labor Ministry’s Migrant Workers Division declined to answer any questions at all. Asked for an interview to discuss concerns that the thousands of Myanmar nationals working in or headed for Malaysia were being exploited, the division said it had “other important matters” to tend to.

But government documents reveal that the Labor Ministry blacklisted Diamond Palace Services last year.

On May 31, the ministry sent the company’s managing director, U Thein Than, the retired army officer, a letter suspending his overseas employment service license — effectively shutting down his own, in-house employment agency — for one year. The letter, a copy of which The Irrawaddy has seen, says Diamond Palace had not followed the proper procedures for sending workers abroad, failed to follow regulations and overcharged workers.

Despite the suspension, the company continues to run the OSC with Bukti Megah.

Routine physical

The MOEAF said there was no open tender process when Diamond Palace landed the OSC deal.

Al Jazeera reported that Bukti Megah did business the same way. In the same “101 East” program that quoted Sim, Al Jazeera said company director Abdul Halim Suleiman, an ex-lawmaker, was a senior member of the United Malays National Organization party, which led the then-ruling Barisan Nasional coalition. His company, it said, was one of three the Malaysian government hired — without an open tender process — to run a new program to legalize migrant workers who were in the country illegally.

Once Diamond Palace and Bukti Megah joined forces to open the OSC, U Kyaw Htin Kyaw said, U Thein Than met with the MOEAF to unpack the deal. He said U Thein Than told the agencies that, of the $51 the OSC would be charging workers on top of the $6 visa fee, Diamond Palace would keep $25 and Bukti Megah the rest. The Diamond Palace director said the OSC was Malaysia’s idea and that he was merely following instructions.

Bukti Megah did not reply to a request for comment.

The four health clinics in Yangon that screen Malaysia-bound workers all declined requests for an interview.

Bestinet, the Malaysian firm that vetted and approved the clinics for the program, was more forthcoming.

The company told The Irrawaddy it earns 100 ringgit (about $25) on every health check, a little less than half the $56 the employment agencies say they cost. Any charges above its own cut, Bestinet added, go to the service providers in Myanmar.

Asked who should be paying for the health checks, the workers or their employers, Bestinet declined to comment.

But the company said its Foreign Worker Centralized Management System (FWCMS) has helped workers and employers both — workers by reducing the time they have to wait for their test results from weeks or months to a few days, employers by weeding out impersonators and anyone trying to pass off forged medical reports.

“What we are trying to do is to protect the migrant worker’s rights and helping them save time and money,” it said. “We refute the allegations made and would like to stress that we are not a ‘paper shuffling’ company as the system brings significant benefits to all principle-centered stakeholders.”

Last year, the Nepali Times reported that Bestinet secured its contract with the Malaysian government thanks to its connections with top officials. It said the company was run by the brother-in-law of then-Home Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, and that Hamidi’s brother and another ex-minister owned shares.

A few days after the report, Bestinet issued a statement denying the claims.

The Nepali Times, citing private FWCMS data, also reported that the new system had not cut down on the number of Nepali migrant workers being sent back home for failing health checks on arrival in Malaysia.

Bestinet told The Irrawaddy its observations suggested the number of migrant workers from Myanmar failing their health checks in Malaysia has dropped “significantly.” But it declined to disclose any figures, claiming the data was confidential and privy to the Malaysian government.

Myanmar’s employment agencies do not see the figures, either. But they said that if Bestinet has cut down on migrant workers failing their health checks in Malaysia, it has not been by much.

One agent said the numbers were always low and may have dropped about half of a percent since Bestinet took over. U Kyaw Htin Kyaw acknowledged that some of the clinics in Myanmar that screened prospective migrant workers before had done a poor job but said he had seen no change in the number of migrant workers failing their health checks in Malaysia since Bestinet took charge.

A new deal

U Kyaw Htin Kyaw said that in the months after the National League for Democracy took power in early 2016, the MOEAF again urged the Labor Ministry to close the OSC and hand the visa process back to the Embassy of Malaysia.

But he said the Labor Ministry claimed to have no jurisdiction because the OSC was under the purview of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

U Kyaw Htin Kyaw said the federation was reluctant to approach the Foreign Affairs Ministry because, as a group representing employment agencies, it was expected to address all its concerns to the Labor Ministry. He said the MOEAF petitioned the Foreign Affairs Ministry anyway, but never heard back.

State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the country’s de facto leader, took personal control of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs after the National League for Democracy took office.

U Kyaw Htin Kyaw was not surprised that the ex-generals who ran the previous government ignored the federation’s complaints about the company of a retired army officer. But he has been disappointed by the ministry’s silence now that it is under the direct charge of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who rose to power on the promise of an end to Myanmar’s crony capitalism.

“She must be able to solve this problem, we [thought] before,” he said. “But now we don’t know.”

The MOEAF spokesman said he would like to see Myanmar and Malaysia strike a deal similar to the one Malaysia made with Nepal in October, putting all fees and recruitment costs on the employers.

Hall, the migrant worker rights specialist, agreed that Myanmar should be negotiating a deal with Malaysia similar to Nepal’s.

“There should be an end to corrupt syndicate processes that result in higher charges, or employers should have to bear the higher costs from the syndicate or privatized visa, health check and ISC processes,” he said.

And where possible, he added, “Malaysian employers should hire directly from Myanmar agencies, bypassing the corrupt and risky system involv[ing] Malaysian agents.”

In the meantime, the problem is only getting worse. With Bangladesh and Nepal still officially closed off to Malaysia, the country’s factories and construction companies are turning ever more to Myanmar to fill the gap in cheap labor. Where Myanmar used to send 3,000 to 4,000 migrant workers to Malaysia each month, it is now sending 5,000, said U Kyaw Htin Kyaw.

M. Kulasegaran, Malaysia’s human resources minister, did not reply to multiple requests for comment.

In December he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation that his administration, which achieved a surprise election victory last year over a corruption-mired coalition that had been in power for decades, was reviewing the country’s policies on migrant workers. He said it was moving to eliminate the Malaysian middlemen who have raised the costs of landing a job in the country by wedging themselves between workers and employers.

Pereira, of the North South Initiative, said the Malaysian government did recently ban companies that used to technically hire migrant workers as their employees but farm them out to the companies were they actually worked. Now, the places migrants work must be their primary employers.

But he said the administration has shared little information about its grander reform plans with the public or groups like his, and has yet to release a copy of the new labor supply deal it signed with Nepal in October.

Pereira said the Malaysian government should try to take back full control of the migrant worker pipeline to put accountability squarely back in its hands, and cut out the “profiteering” private companies the previous administration outsourced it to.

“All of them should be sacked,” he said of the companies. “If the duty is given to the government, they should enforce it a bit more.”

He said the workers themselves also had to be better educated about the risks they were taking coming to Malaysia.

Given all the pitfalls, “I don’t understand why they still want to come to Malaysia to work — Malaysia is a terrible place for migrants,” Pereira said. “You can get more money…but the living conditions, the racism, the fear is terrible.”

U Kyaw Zaw Linn, director of Myanmar’s Migrant Workers Rights Network, said Naypyitaw should be paying at least as much attention to cleaning up the migrant worker pipeline as Kuala Lumpur, but he has seen scant evidence of it.

“They never pay attention to Malaysia. I don’t see any action,” he said.

“They need to understand what is the situation, what is happening on the ground,” he added. “Why [do] we need to pay the One Stop Center? For what? Is it fair or not? They need to think.”

U Kyaw Zaw Linn said the government should find a way to bring the costs down, or at least take the burden off workers. But he was open to more extreme measures.

Taking a cue from Nepal, he said, “If they can’t control the cost, they need to close. They need to stop sending workers to Malaysia.”