YANGON—While caves themselves have not generally been the subject of environmental conservation efforts in Myanmar, the widespread custom among the country’s Buddhist majority of placing Buddha images or building stupas and shrines on mountains and hills, as well as inside caves, has helped to protect them from total destruction.

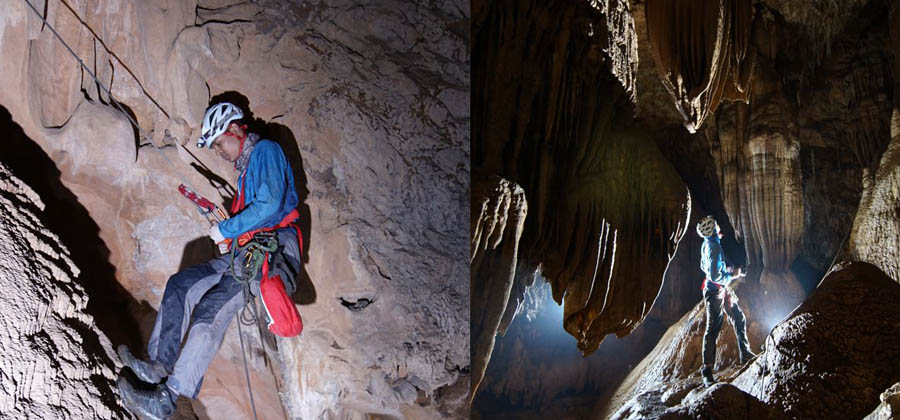

Buddhist religious sites are considered places of worship for adult pilgrims and a wonderland in which to play for children. One of the few people who turned this childhood wonder into an adult effort to preserve such sites is climber and cave researcher Ko Nyi Nyi Aung. He has been a mountaineer for 14 years and participated in the Myanmar Everest Expedition in 2016, in which two of his colleagues became the first climbers from Myanmar to reach the summit of the world’s highest peak.

“I became interest in hiking and mountain climbing when I was about 7, while accompanying my father on visits to pagodas—like the mountaintop Kyaiktiyo in Mon State and other famous pagodas in nearby Karen State and around the country—to meditate,” Ko Nyi Nyi Aung said.

At university, he joined the Invitation of Nature climbing club in order to achieve his dream of “climbing a snow-capped mountain.”

Two years ago, Ko Nyi Nyi Aung built on his climbing skills and began learning speleology—the study and exploration of caves. He is also a main coordinator of the Myanmar Cave Documentation Project (MCDP), a group of experienced speleologists founded by Joerg Dreybrodt and a few other international experts in September 2008. They provided cave documentation training to local spelunkers in collaboration with Fauna and Flora International (FFI) in June 2017.

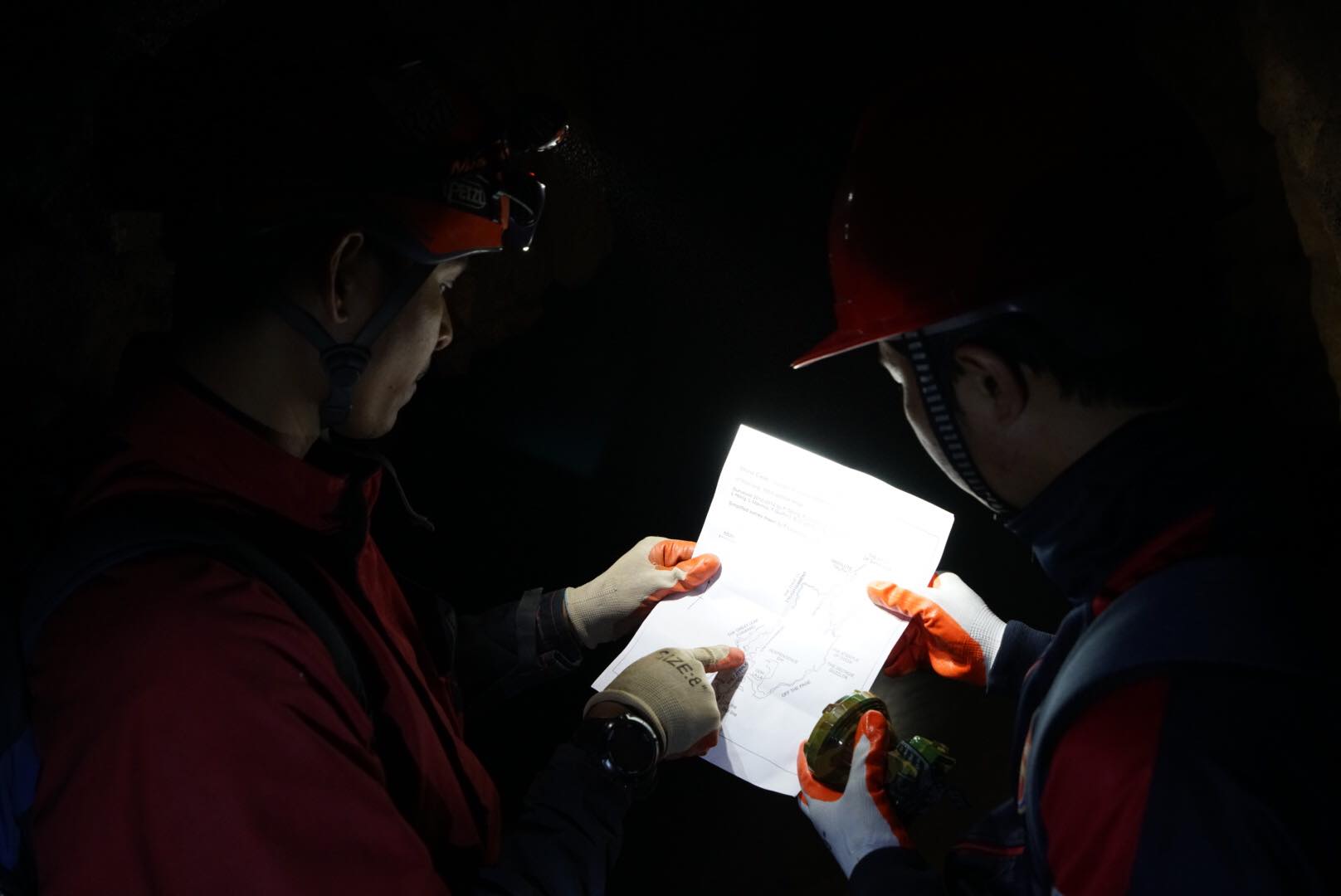

Nineteen Myanmar cave documenters participated in a joint expedition team with international speleologists early this year in February and March. Prior to that, cave expeditions in Myanmar were mostly limited to international speleologists, as few Myanmar people have been involved in cave surveying.

“Some of the caves we found are not even easily noticeable as caves, as [their entrances] are located near villages, or in the middle of plantation fields,” Ko Nyi Nyi Aung said. When they proceed inside such sites, away from the entrance, they realize they have found an unexplored cave. MCDP has surveyed and mapped more than 600 caves.

The longest caves in Myanmar are located in Shan State’s Ywangan and Pinlaung townships and Kayah State’s Loikaw, Hpruso and Bawlakhe townships. Surveying of these caves began in 2012 and is ongoing. Additionally, since 2009, international speleologist expeditions have conducted yearly surveys of caves in Karen, Kayah and Shan states, as well as in Mandalay and on the Myeik archipelago in Tannitharyi Region.

Among tourists, the most popular caves in Myanmar are connected to religious sites, such as the Pindaya and Htam Sam caves in Shan state; Peik Chin Myaung in Pyin Oo Lwin, Mandalay Region; Saddan, Kawgun and Yathay Pyan caves in Karen State; and U Min Thonze cave and Pho Win Daung cave Sagaing Region.

Preservation is the responsibility of the pagodas’ trustees or local communities; such efforts currently lack wider support from the government’s Archeological Department. The government only takes an active part in preserving a few caves considered historic landmarks such Padah-Lin cave in Ywangan, an archeological site founded in 1960.

Some caves close to mining areas are in particular danger of being destroyed, Ko Nyi Nyi Aung said. Some limestone caves are near quarry sites; the presence of armed guards at these locations hinders access to the caves by study teams.

In Myanmar, cement companies tend to have a lot of information about limestone caves, as they conduct surveys to extract limestone in specific areas.

Ko Nyi Nyi Aung said, “Many of our caves are spared from complete destruction as they are protected by Buddhist monks. We are familiar with the caves as pilgrims sites, and have had some exposure to them, but we lack deeper knowledge about these caves for various reasons.”

“It is true that the ecosystems of these caves are sometimes destroyed when structures are built in them, sometimes using cement; but [at least] they are preserved as caves. So there are both advantages and drawbacks [to their religious use],” he added.

Having existed for millions of years, caves are “natural museums” allowing scientists to study various species of animals and other natural phenomena, Ko Nyi Nyi Aung said. Awareness of the need for preservation is growing among local residents, he said, thanks to FFI’s workshops to educate villagers.

He said that from his experience, locals are often already aware that guano (droppings) deposited by bats inside caves makes good natural fertilizer for agricultural use, adding that many villagers are now also aware that bats play a role in pollination, and that every species is vital to the survival of its particular ecosystem.

“Locals realize that the stalactites and stalagmites in the caves take millions of years to form. If they preserve the caves, they will attract tourists and thus could increase their income. Now they have become aware of that,” he said.

Acknowledging the need for further awareness raising, Ko Nyi Nyi Aung said he understands that local villagers sometimes cause unintentional damage to the natural environment in their efforts to make a living from the land.

“If they were aware, they would surely preserve these natural resources, but it will take time,” said Ko Nyi Nyi Aung, adding that there is already a strong network of speleologists, local teachers and residents working to preserve the caves.

FFI’s preservation workshops have also encouraged locals to develop more ideas for ecotourism businesses, as well as to become more aware of good safety habits. At the Elephant Whirlpool River cave in Ywangan’s Kyauk Nget village, he said, the local tea shop outside the cave reminds the tourists to use helmets for their safety, and also makes money by selling batteries and other necessities to those entering the caves.

“Also, at that cave, the locals’ awareness is strong. Though they are Buddhists, they have refrained from putting up any Buddha images or stupas inside the cave,” Ko Nyi Nyi Aung said. “The stairs are made from bamboo, not concrete. Sandbags are used for steps and these are regularly changed and not allowed to decay. And we don’t see any writing in correction markers on the walls of the caves. They do a really good job of preserving their caves and this is an example for all of us to follow,” he said.