Recent years have seen dramatic changes to Burma’s media landscape, with the previous quasi-civilian government taking steps to unshackle a press corps long muzzled by successive military regimes dating back to 1962.

In the wake of World Press Freedom Day, which was celebrated on Tuesday, The Irrawaddy revisits a media history stretching back to the 1800s.

2011 – 2015

2015 — Much of the year’s news coverage is devoted to the Nov. 8 general election, Burma’s first poll in more than half a century to take place in a relatively free media environment. The Myanmar Times, for 15 years a weekly, goes daily in March, taking up the mantle of Burma’s only English-language daily newspaper, a title previously held by the now defunct Myanma Freedom Daily.

2014 — The year begins inauspiciously for Burma’s media with the detention of four journalists and the CEO if the Unity journal in connection with a January report alleging the existence of a government chemical weapons factory. Charged and convicted under the State Secrets Act, the men were sentenced to 10 years in prison, which was later reduced to seven. The men were released as part of a broader amnesty by the new government last month.

March sees passage of two new media laws that are received with mixed reactions, while the press corps is rocked to its core in October by news that the freelance journalist Par Gyi was killed while in military custody. No one was ever convicted of a crime in the case.

2013 — On April 1, four Burmese-language private dailies begin publishing after the government granted licenses to 16 private dailies. In August, Myanma Freedom Daily emerges as the first English-language daily in almost five decades. The paper folds less than a year later.

According to government figures, the Information Ministry has so far issued 35 licenses for private and state-run dailies, and 22 are in publication. It has granted licenses for 32 news agencies, of which 23 are in operation. And 260 out of 437 licensed journals are being published.

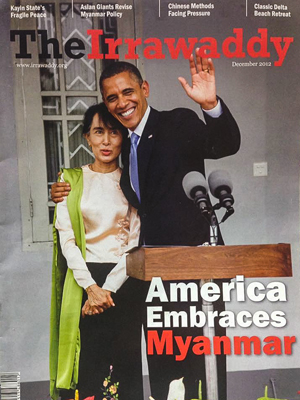

2012 — President Thein Sein’s government allows international news agencies, which were technically banned under the military regime, to conduct reporting in Burma. Exile media like The Irrawaddy are also allowed to return. Founded by Aung Zaw in 1993, The Irrawaddy distributed its magazine for the first time in Burma in December 2012, and also shifted its online operations to Rangoon while maintaining a small office in Thailand’s Chiang Mai. The Irrawaddy published its first Burmese-language weekly in January 2014, and switched to an all-digital format early in 2016.

2012 — President Thein Sein’s government allows international news agencies, which were technically banned under the military regime, to conduct reporting in Burma. Exile media like The Irrawaddy are also allowed to return. Founded by Aung Zaw in 1993, The Irrawaddy distributed its magazine for the first time in Burma in December 2012, and also shifted its online operations to Rangoon while maintaining a small office in Thailand’s Chiang Mai. The Irrawaddy published its first Burmese-language weekly in January 2014, and switched to an all-digital format early in 2016.

The Burma Press Council (Interim) is formed with 29 members on Oct. 17.

As part of its media reforms, the government announces in December 2012 that it will allow the uncensored publication of private daily newspapers, dissolving its notorious Press Scrutiny and Registration Division under the Information Ministry in a follow-up move after it did away with decades-long draconian pre-publication censorship in August 2012.

2011 — With the Thein Sein government coming to power, local publications in Burma are allowed to feature articles written by—and interviews with—pro-democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi for the first time.

1988 – 2010

* In 1988 Burma enjoyed press freedom for the short time of one month due to pro-democracy uprisings. In 1997 Burma was labeled as the regions number one adversary of the press. Today, it has about 100 publications, all censored by Press Scrutiny Boards.

2007 — Kenji Nagai, a Japanese photojournalist seasoned in conflict reporting, is shot dead by a Burma Army soldier during the 2007 anti-government protests in Rangoon. The 50-year-old was the only foreign national killed in the protests. The military regime of the time, which ruled as the State Peace and Development Council, ultimately quashed the demonstrations and continued to hold a tight grip on the media until Thein Sein’s government came to power in 2011.

April 28, 2004—An international pro-democracy group, Freedom House, ranks Burma as one of the top five “Worst of the Worst” countries for press freedom in the world.

February 2000—The English-weekly Myanmar Times & Business Review is launched by an Australian businessman and military officials. Sonny Swe, the son of Brig-Gen Thein Swe who is a high ranking Military Intelligence officer, is the deputy CEO of the journal. Later, it starts to publish a Burmese-language version.

February 2000—The English-weekly Myanmar Times & Business Review is launched by an Australian businessman and military officials. Sonny Swe, the son of Brig-Gen Thein Swe who is a high ranking Military Intelligence officer, is the deputy CEO of the journal. Later, it starts to publish a Burmese-language version.

1997—US-based Committee to Protect Journalists, or CPJ, describes Burma and Indonesia as the region’s two foremost enemies of the press. Yet, since the fall of Suharto in the same year, Indonesia’s mass media blossoms, leaving Burma as the region’s number one adversary of the press.

Mid-1990s—The junta launches the Kyemon that was also nationalized in 1964.

Mid-1990s—The junta launches the Kyemon that was also nationalized in 1964.

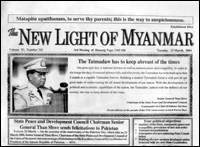

April 1993—The regime changes the name of the Loktha Pyithu Nezin (the Working People’s Daily) to Myanma Alin (the New Light of Myanmar) that was banned in 1969.

1989—After taking power again, the military amends the 1962 Printers and Publishers Registration Act to heavily increase the fine payable by offenders.

September 1988—Immediately after the military ceases power on September 18, all newspapers are banned except for the Loktha Pyithu Nezin and its English version, the Working Peopl’s Daily. Strict censorship is imposed and many journalists are arrested.

At first, foreign journalists are allowed into the country but later they are banned and only a few selected foreign journalists are given press visas.

August – September 1988—After 26 years of silence, about 40 independent newspapers and journals, including the Light of Dawn, the Liberation Daily, Scoop, the New Victory and Newsletter, appear in Rangoon for about a month during the period of nationwide pro-democracy uprisings. The publications run political commentaries, biting satires and humorous cartoons of the rulers.

Even the state-run newspapers like the Guardian and the Working People’s Daily publish outspoken political articles.

1958 – 1970s

* About 30 newspapers emerge. The year 1964 is said to be Burma’s last year of press freedom. At this time, dictator Ne Win’s Revolutionary Council shuts down some newspapers and nationalizes most newspapers.

1974—The Socialist party’s new constitution grants freedom of expression. However, all forms of public expression are subject to Press Scrutiny Boards to ensure that these “freedoms” are only expressed within the accepted limits of the ‘Burmese Way to Socialism.’

1969—The right-wing Hanthawaddy and the Myanma Alin (the New Light of Burma) are nationalized. Eventually, only six newspapers are left: the Loktha Pyithu Nezin, the Botataung, the Kyemon and the Hanthawaddy, the Guardian and the Working People’s Daily.

The News Agency Burma controls the flow of news in and out of the country. All foreign correspondents, except those working for the Soviet Tass and China’s Xinhua, are expelled. Visits by foreign journalists are officially banned. Locally based foreign news agencies are forced to appoint Burmese citizens as correspondents that must be approved by the authorities. In the late 1990s, the British Broadcasting Company and the Voice of America pull out after being unable to appoint their own correspondents.

1966—The government announces that private newspapers are to be banned altogether.All Chinese and Indian language newspapers are stopped as printing is required to be done in Burmese or English language only.

1964—Said to be the last year Burma enjoyed a free press, the government nationalizes all private newspapers, the liberal Kyemon (theMirror), Botataung (A Thousand Officers) and the Guardian. The left-wing Vanguard offers itself for nationalization. Smaller newspapers are shut down and several editors and journalists are arrested.

October 1963—The government launches the Loktha Pyithu Nezin (the Working People’s Daily) to compete with exiting private newspapers. In January 1964, the English version of the Working People’s Daily appears.

July 1963—The government establishes the News Agency Burma.

1963—The military government closes down the Nation, an outspoken defender of press freedom, arresting its editor Law Yone three months later.

1962—The Burma Press Council, or BPC, is founded “to promote and preserve freedom of the press through a voluntary observance of a code of press ethics.” Writers and journalists from 52 newspapers, journals and magazines signed the BPC Charter.

Later that year, the Dictator Ne Win’s Revolutionary Council revokes all existing press laws and enactes a single law, the Printers and Publishers Registration Act. The act establishes Press Scrutiny Boards to scrutinize all material prior to publication, or in some cases after publication.

1946 – 1957

* About 70 newspapers come out during this period.

April 16, 1957—The Mirror Daily, the Reporter Daily and the Pyidawsoe News Daily appear on Burmese New Year day.

August 21, 1949—The parliamentary government introduces a Bill in Parliament to limit press criticism, saying: “Any person, making criticism, defamatory allegations or charges concerning public servants, including ministers, and officials, would be recognized as committing a criminal offense.”

1948—Burma gains independence. There are 39 newspapers published in various languages throughout the country. Seven of the papers are printed in English, 11 in foreign languages, five in Chinese and six in Gujarati, Urdu, Tamil, Telgu and Hindi.

1947—Burma’s first constitution guarantees citizens the right to freely express their opinions and convictions. This gives the country a reputation for having one of the freest presses in Asia.

1935 – 1945

* More than 60 newspapers emerge across the country, including Japanese-language and ethnic newspapers.

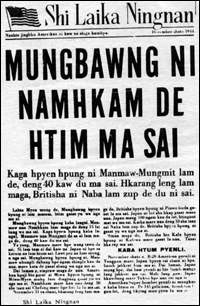

1943 – 1945—Kanbawza newspaper, the Kachin-language Shi Laika Ningnan, the Rangoon Liberator, the Shwe Man Aung Si, Tai-4, the British government published New Age, the Tavoyan, the Lanhnyun Daily, the Freedom, the Morning Star, Burma Economic Daily, the People’s Voice and the Guide Daily are all in circulation.

Kachin’s Shi Laika Ningnan is printed in India and airdropped into the Kachin-inhabited area of northern Burma.

September 1942—Domei News Service publishes a Japanese daily newspaper.

1942—The Tavoy Daily appears in Tavoy. The New Light of Burma and the Sun emerge again. Bamakhit and Mandalay Thuria appear.

1941—A Christian newspaper, the Sower and the Daily Mirror appear in Rangoon.

1940—The Mon Bulletin, the Student, World Telegrams Daily and Saturday News are published in Rangoon and Mandalay.

1939—The Advance Daily, the Burmese News Mandalay, the Shwe Pyi Daw (Burma News), Thakin Thadinsa, the Local Bodies, Lu-Nge-Let-Yone Daily and the Nationally Daily are published in Rangoon and Mandalay.

1938—The Progress, the Aazaanee, Burma’s Voice, the Deedok Daily and the Leader emerge in Rangoon and Mandalay. The editor of Deedok, Ba Cho, is assassinated together with national leader Aung San on July 19, 1947.

1937—Doat-Let-Yone (the Arm), claiming to be the only Arakan-language paper, is published in ArakanState. Asariya and the 10, 000, 000 (the Ten Million) are set up in Rangoon.

1935—The Rakhine-Pyi-Thadinsa, an Arakan newspaper, is published in Sittwe for four years. Ye newspaper, the Myanmar Uzun, the Burma Daily Mail and the Burmese Improvement come out in Rangoon and Mandalay.

1924 – 1934

* About 40 new newspapers emerge, tripling the number of papers since the press laws of 1908 and 1910 are repelled and amended.

1934—The Mawriya Daily appears.

1933—Myanma Myochit, Daung-Settkya, the Laborer, the Success, Daung, the New Mandalay Sun Daily and the Evening Report appear.

1932—Tharrawaddy, Anawyahtar, the Myanma Zeyyar, the Ma-Haw-Tha-Dha and the Rangoon Optic newspapers emerge.

1931—Ratanathiha and Lawkasara Daily News come out in Sibaw, ShanState and Rangoon.

1929—Kesara, the Burma Advertiser, the Burman and the Mandalay Daily Supplement to the Sun are set up in Rangoon, Mandalay and Moulmein.

1928—The National Observer and the Shwenannyun Gazette are published in Rangoon and Mandalay.

1927—The Bandoola, the Traders Spectacles, the pro-British Headman’s Gazette, Essence of Buddhism and another Dhamma newspaper emerge in Rangoon.

1926—The Myanma-Myo-Nwe, Aung Myanma, Mawrawadi News, the Shwe Pyi, the Ledi Religious Instructor are published in Rangoon.

1925—The Independent Weekly, the Truth, the Market Report, the Victor (Zeya), the Trades Exchange and the Silver Moon come out in Rangoon and Mandalay.

1924—The Burmese-language Yarmanya and the Myochit newspapers appear in Moulmein and Rangoon.

1913 – 1923

* One of the longest-running newspapers, still being published by the junta today, Myanma Alin (the New Light of Burma), appears in 1914. Associated Press of India, known as API, opens an office in Rangoon and a Muslim newspaper also emerges.

1923—According to an official statement, there are 31 newspapers being published in Rangoon, Mandalay, Moulmein, Sittwe, Bassein and Tharawaddy.

1923—The Associated Press of India, known as API, opens an office in Rangoon.

1923—The Muslim Herald, the Comet, the Burmese Review and the Myanmahlut News are established. Fair Play (in Karen and English), the Rangoon Daily News and the Irrawaddy Times (in Burmese and English) are already being published. The Wunthanu (the Patriot) is also published in Rangoon with a circulation of around 5,000.

1922—The Karen Times and the New Leader appear in Rangoon and Mandalay. The following year, the New Leader changes its name to Shae-saung. In October, the Servant of Burma emerges in Rangoon. The Myanma Myo Taw Saunt and Aungzeya newspapers also begin to be published.

March 1922—The Press Law Repeal and Amendment Act is enacted. The act allows the authorities to confiscate any newspaper that runs news and opinion pieces considered as instigating revolt against the government.

1921—Burma’s Progress is published by the British government but stops two years later.

1921—The Home Rule is published in Mandalay.

1920—The New Burma is set up in Rangoon and continues to be published until 1942.

May 1919—Myanma Alin Thadinsa Athit (a second New Light of Burma) is published in Rangoon.

1918—The Knowledge (Pyinnya Alin) and the Burma Observer are published in Rangoon. The paper is halted in 1924 and again in 1929.

1917—The Burma Guardian and the Rangoon Mail are published in Rangoon. The Tharrawaddy Record is set up in a town near Tharrawaddy, central Burma, with a female editor.

1914—Thuria and Myanma Alin publish a newsletter called War Telegrams about World War I. Thuria‘s circulation reaches about 10,000.

August 1914—Myanma Alin (the New Light of Burma), an outspoken newspaper, appears no later than May 1919. It is published three times a week in Burmese. In December 1924, it becomes a daily newspaper until its publication ceases in 1929.

1901 – 1912

* Reuters News Agency opens in Rangoon. Other outspoken newspapers appear, such as the Thuria (the Sun). By 1904, there are about 15 newspapers running with circulations of up to 1,500. New newspapers continue to be established.

July 4, 1911—One of the most outspoken Burmese-language newspapers, Thuriya (the Sun), emerges three times a week. In March 1915, it becomes a daily newspaper and continues to be published until October 14, 1954. In the same year, the Salween Times appears in English.

Newspapers Running in 1910s:

The Rangoon Gazette, the Rangoon Times, the Friend of Burma, the Rangoon Advertiser, Publicity, the Maha-Bodhi News, the Burma Herald, the Burma Printer News are all published in Rangoon.

The Upper Burma Gazette, the Mandalay Herald, the Star of Burma, the Mandalay Times, Moulmein Advertiser, Moulmein Gazette and the Burma Times are all published in Mandalay.

1909—The Dawkale, published in the Karen-language of Sagaw, is published once a week by Karen Magazine Press in Bassein, Irrawaddy Division.

1908—The Burma Commercial Advertiser is published twice a week in Rangoon.

November 1907—The Burma Educational Journal is established.

May 18, 1907—The Burma Echo appears once a week in Rangoon.

April 1907—The Burma Critic begins publication in Mandalay. In the same year, a religious newspaper with the name of Dhamma Day-Tha-Nar Thadinsa appears.

August 2, 1904—The Burma Printer News emerges three times a week in Rangoon, but is stopped three years later.

July 22, 1903—The Myanmahitakari Fortnightly Journal is established.

1903—A Reuters News Agency office opens in Rangoon.

March 3, 1901—The religious Maha-Bodhi News appears once a week in Rangoon and continues to be published up until 1926.

1880 – 1900

* King Thibaw, the last Burmese monarch, is removed and Upper Burma is annexed by the British. One of the most outspoken newspapers,Hanthawaddy Thadinsa, is established along with some other new newspapers.

1900—The pro-British Burmese-language Star of Burma is published in Mandalay. It continues to be published up until 1948.

1899—The Times of Burma and the Upper Burma Gazette are established in Rangoon and Mandalay.

February 1895—The Mawlamyaing Myo (MoulmeinTown) is published in Moulmein.

1894—The English-language newspapers, the De Vaux Press Advertiser, the British Burma Advertiser, the Rangoon Commercial Advertiser and the Burma Chronicle News are all being published in Rangoon. De Vaux Press Advertiser’s circulation was said to be around 1,000 a day.

The Karen National News, the Bassein Weekly News and the Advertiser are also published weekly in Bassein, Irrawaddy Division. The Karen National News written in the Karen-language of Sagu (Sgaw) reaches circulation of about 500.

1892—The English-language papers, the Daily Advertiser, the Arakan Echo and the Arakan Advocate are established in Sittwe. Later, the Daily Advertiser and the Arakan Echo combine to form the Arakan Times.

1889—The Hanthawaddy Thadinsa (the Hanthawaddy Weekly Review) appears twice a week in Rangoon. It is regarded as one of the most outspoken newspapers of its time. The newspaper covers foreign news from Reuters news agency through an agent. In 1904, its circulation reaches about 1,000.

March 3, 1887—The Mandalay Herald emerges three times a week in Mandalay. It becomes a daily in 1899 up until 1902, when the paper stopped being published.

1886—The Mandalay Times newspaper appears twice a week in Mandalay.

1884—The English-language weekly, the Maulmain Almanac, is published in Moulmein. The Burmese-language Friend of Burma is also set up in Rangoon and eventually becomes a daily newspaper before its publication stopped in 1929.

1869 – 1879

* Freedom of the press is guaranteed by King Mindon, the second last Burmese monarch, in an Act of 17 articles that is regarded as Southeast Asia’s first indigenous press-freedom law. The Kingdom publishes an official newspaper.

March 11, 1878—The British government enacts a law called the Vernacular Press Act to ban newspapers from reporting and picturing defamation of the government.

1878—The Burma Herald is set up by the King of Mandalay to counter the pro-British views of Rangoon newspapers. Two other English newspapers, the Rangoon Daily Mail and the Daily Review, are established and halted six months later.

1876—The Burmese-language Tenasserim Thadinsa (The Tenasserim News) appears in Moulmein.

March 20, 1875—Yadanabon Nay-Pyi-Daw (with the heading of Mandalay Gazette in English on the masthead) is published weekly by King Mindon, possibly as early as 1874. Publication ceases in 1885 when Upper Burma is annexed by the British.

1875—Yadanabon Thadinsa (British Burma News) appears in Rangoon.

August 15, 1873—King Mindon (1853 – 1878) bestowes immunity on the local press corps with the introduction of an act consisting of 17 articles that ensure freedom of the press.

November 1874—The Burmese-language Friend of Maulmain newspaper appears in Moulmein.

January 11, 1873—Law-Ki-Thu-Ta (the Worldly Knowledge) newspaper emerges in Rangoon.

May 8, 1871—The Burmese-language paper, the Burmah Gazette, appears in Rangoon. This weekly newspaper alters its name to the Burma News in May 1872. It ceases publication in 1916.

1869—Myanmar Thandawsint Thadinsa (the Burmah Herald) is published once a week by Myanmar Thandawsint Press, possibly as early as 1871. It is the first Burmese-language newspaper in Rangoon. In 1884, it becomes a daily with a circulation of around 500. It ceases publication in 1912.

1858 – 1868

* At least three new newspapers emerge. There are six newspapers being published during this period.

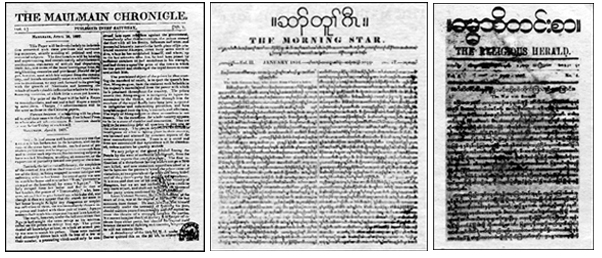

1862—The Dhamma Thadinsa (the Religious Herald), first published by the Baptist mission in 1843, changes its name to the Burman Messenger.

The Times Commercial Advertiser, the Daily Advertiser, Pole Star, British Burma Gazette, the Mercantile Gazette and the Arakan News are still published during this period according to newspaper research conducted in 1868.

1861—The Rangoon Gazette is established as a rival of the Rangoon Times. It is published twice a week and later daily. It ceases publication in 1942.

June 2, 1858—The English-language Rangoon Times is published, possibly as early as 1854. The newspaper began as a twice-weekly publication, however, it increased to three times a week by 1861 and later became a daily. It ceased publication in 1942, when the British left Rangoon.

1847 – 1857

* About four English-language newspapers emerge. One is published by ethnic Arakan in the capital of Sittwe, Arakan state. The British legislation council enacts a law, known as the “law to shut mouth” banning the publication of news without prior approval.

June 13, 1857—Lord Canning, the Governor General of India from 1856-1862, introduces a law banning the publication of any news without prior approval in an attempt to regulate the press.

1853—The twice-weekly English-language Akyab (Sittwe) Commercial Advertiser is published in Sittwe, by Arakan Weekly News Press. The following year, the paper changes its name to the Arakan News. Circulation reached about 150.

January 5, 1853—The Rangoon Chronicle newspaper is published twice a week. Later, it changes its name to the Pegu Gazette. It ceased publication in May 1958.

1849—A weekly publication, the English-language Friend of Burmah newspaper, starts in Moulmein.

July 1, 1848—The English-language paper, the Maulmain Advertiser, is published in Moulmein. It may have first appeared as early as 1846. The paper, published three times a week by W. Thomas & Co, altered its name to the Maulmain Times in 1850, but the following year it resumed its previous name.

1836 – 1846

* During this period the first English-language newspaper was launched under British-ruled Tenasserim, southern Burma. The first ethnic Karen-language and Burmese-language newspapers also appear in this period.

1846—The Maulmain Free Press newspaper is published by an English merchant in Moulmein.

January 1843—The Baptist mission publishes a monthly newspaper, the Christian Dhamma Thadinsa (the Religious Herald), in Moulmein. Supposedly the first Burmese-language newspaper, it continued up until the first year of the second Anglo-Burmese War in 1853. In 1862 the paper resumed publication under a different name, the Burman Messenger.

September 1842—Tavoy’s Hsa-tu-gaw (the Morning Star), a monthly publication in the Karen-language of Sgaw, is established by the Baptist mission. It is the first ethnic language newspaper. Circulation reached about three hundred until its publication ceased in 1849.

March 3, 1836—The first English-language newspaper, The Maulmain Chronicle, appears in the city of Moulmein in British-ruled Tenasserim. The paper, first published by a British official named E.A. Blundell, continued up until the 1950s.

References:

Index of Burma Newspapers, Volumes 1 and 2, by Htin Gyi

A Journalist, A General and An Army in Burma, (1995), by U Thaung

Inked Over, Ripped Out, by Anna J. Allott

Burma, Laos, and Cambodia, Status of Media in, by Bertil Lintner

His Majesty’s Newspaper, by Htin Gyi

Some Early Newspapers in Myanmar, by Hla Thein

Research by Kyaw Zwa Moe.

Additional Updates: Thet Ko Ko & Wei Yan Aung.