YANGON — Pakistan has recently halted agreements reached under China’s Belt and Road Initiative, including the Pakistan-China Economic Corridor seeking to connect Asia and Europe along the same route as the ancient Silk Road, because it was found to unfairly benefit Chinese companies.

Malaysia has also announced the cancellation of two major infrastructure projects, with a total value of $23 billion, which make up part of the Belt and Road Initiative in order to avoid falling into a debt trap.

While several Asian countries have scrapped mega projects planned under Chinese president Xi’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative in their countries, Naypyitaw’s recent agreement with Beijing for a multibillion-dollar economic project has raised eyebrows over its potential for creating a “debt trap” in a country with a low sovereign credit rating and a low capacity to service the debt.

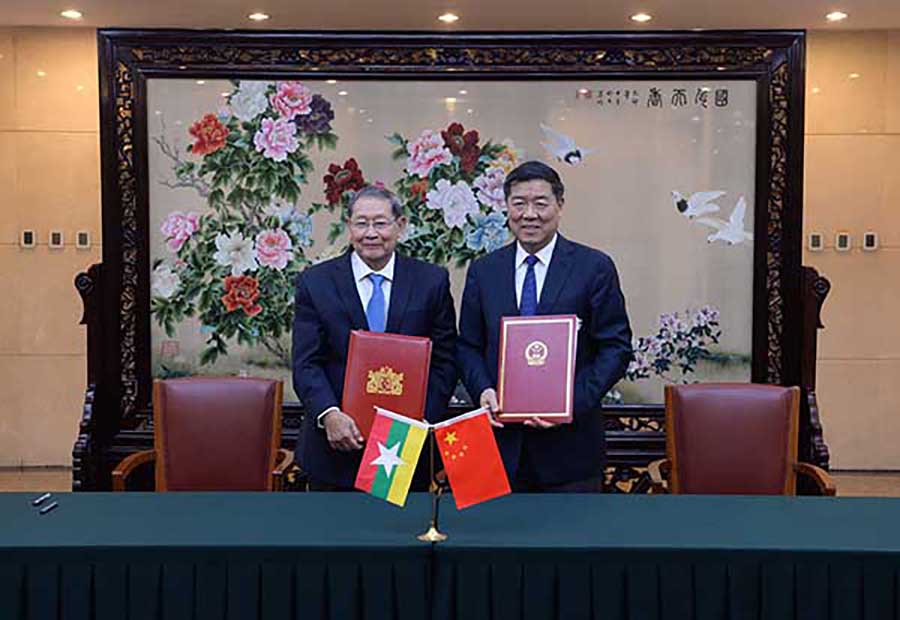

Last week, Myanmar’s planning and finance minister, U Soe Win and the chairman of China’s top economic planning agency, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), He Lifeng signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) on the establishment of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC). It will connect Kunming, the capital of China’s Yunnan Province to the Bay of Bengal at a deep sea port in Kyaukphyu, Rakhine State as part of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) policy, later known as the “Belt and Road Initiative” was unveiled in 2013 and aims to build a network of roads, railways and shipping lanes linking at least 70 countries from China to Europe passing through central Asia, the Middle East and Russia, fostering trade and investment.

In 2017, Myanmar’s State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi attended the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing. An MOU of cooperation within the framework of the “Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative” was signed during the visit.

The CMEC project will be one of the biggest packages of foreign direct investment (FDI) yet under the National League for Democracy’s administration and it comes while Myanmar is struggling with declining of FDI year by year and the country’s image in tatters over the Rohingya crisis in Rakhine State.

The 1,700-kilometer-long corridor will pass through Myanmar’s major economic hubs including Mandalay in central Myanmar, then going south-east to Yangon before turning west to its end point at Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone (SEZ).

According to CMEC proposal, the initial stages of the project include an estimated 24 projects with a total budget of $2 billion which is exclusive of the other major infrastructure projects that will begin in a later stage. From this budget, Myanmar’s Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Irrigation will receive $400 million to develop the irrigation system along the corridor in Myanmar.

In Yangon, as part of the CMEC, the China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) has already proposed the $100 billion New Yangon City, a development project that aims to construct a combination of new cities, industrial parks and urban development projects.

The proposal also includes upgrades to three major roads through Mandalay, Muse on the Myanmar side of the border with China, and some roads in Shan State. The highway and a high-speed railway are expected to cross war-torn Shan and Kachin states. To bolster the success of the strategic plan, China has been making efforts in assisting peace negotiations between Naypyitaw and the ethnic armed groups.

According to Myanmar’s Directorate of Investment and Company Administration (DICA), the economic corridor project will boost basic infrastructure, construction, manufacturing, agriculture, transport, finance, human resources development, telecommunications, and research and technology.

The proposal claimed that the CMEC would allow a direct flow of Chinese goods into the southern and western regions of Myanmar and that Chinese industries could transfer here in order to abate the rising labor cost and overcapacity of China’s industries. It said Myanmar would become a major trade hub between China, Southeast Asia and South Asia.

However, experts are questioning how the infrastructure projects across Myanmar would be financed.

Associate Professor at the Institute of Security and International Studies in the Faculty of Political Science at Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University, Thitinan Pongsudhirak told The Irrawaddy, “The CMEC can take the example of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor in view of other infrastructure connectivity [projects in] China’s Belt and Road.”

“The conspicuous risk is the so-called “debt trap” whereby China lends substantial sums to construct corridor projects and leave recipient countries saddled with debt obligations they will have difficulties repaying. This gives China leverage and influence over recipient countries,” he said.

In March 2018, a report by the Washington-based Center for Global Development said, China is putting many countries under the Belt and Road Initiative at financial risk through a series of aid activities and huge amounts of lending. The report said countries which are at a particularly high risk are Laos, Mongolia, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, the Maldives, Djibouti, and Montenegro.

The head of the US Overseas Private Investment Corporation has echoed this concern, warning that China’s Belt and Road Initiative was creating a debt trap for many poor nations.

A deep-water port project of the Belt and Road Initiative in Sri Lanka was recently handed over to a Chinese state-owned company on a 99-year lease after Sri Lanka failed to make its loan repayments. Sri Lanka is one vivid example of China’s ambitious use of loans and aid to gain influence long the Belt and Road route.

A key strategic project under the Initiative, Kyaukphyu’s seaport is already a major doorway allowing China’s oil imports to bypass the Strait of Malacca and gives China direct access to the Indian Ocean. The project will fulfill China’s dream to boost development in land-locked Yunnan Province.

A recent successful share renegotiation of Kyaukphyu SEZ—also combined with MoU for Economic Corridor, Myanmar is stepping into China’s strategic plan to achieve economic supremacy in the region. China is Myanmar’s unavoidable neighbor geographically and economically at a time when western investment is turning away from the country due to the internationally condemned human rights crisis in Rakhine State.

“Myanmar has no one else to rely on but China. The West is pushing Myanmar into China’s hands,” Yangon-based political analyst U Maung Maung Soe told The Irrawaddy.

“China won’t give up on their strategic plan; they will try to find several ways to move it forward. We need to find a better way of working with them practically,” said U Maung Maung Soe.

Experts have said the Kyaukphyu port could be a key project in the Myanmar, Bangladesh and North East India Economic Corridors for its role as a transport center. Myanmar is already essential to China’s access to fuel supplies as Chinese pipelines having been pumping oil and gas from the port at Kyaukphyu to Yunnan since 2017.

Developing Asian countries like Myanmar, experts have pointed out, are undeniably in need of infrastructure upgrades in order to promote economic development and improve living standards but there are key questions surrounding the ownership, operation and terms of these projects.

“Myanmar will have to eke out favorable terms that are fair and not disadvantages. Laos is a good example of what not to do, of why not be too heavily indebted to China,” Thitinan Pongsudhirak said.

“Myanmar also has to be careful about other strings attached, such as land use rights and other concessions and terms for these projects. Doing so will allow Myanmar to safeguard sovereignty and economic national interest,” he added.

According to a DICA official, the MOU includes 15 points of collaboration between the relative ministries from both sides, but the Myanmar government has not yet released it to the public.

In August, at a seminar titled “Myanmar’s Economy 2018: Progress, Problems, Possibilities” special economic consultant to the Myanmar state counselor, Sean Turnell said that regarding Chinese mega investment, Myanmar needs to consider whether China’s mega-projects are for Myanmar’s national and economic interest or not.

Despite some countries having run into major financial difficulties after Belt and Road Initiative infrastructure projects began, in August vice chairman of China’s National Development and Reform Commission, Ning Jizhe claimed the projects are not a debt trap. He said the countries with debt problems have long-standing high debt levels which shouldn’t be blamed on the Initiative.

“For China, it has to be careful not to be seen as ripping off countries like Myanmar or Laos or Sri Lanka because this could lead to local resentment and pushback against Chinese interests,” Thitinan Pongsudhirak said.